The Long, Weird Transition from Analog to Digital Television

Remember rabbit ears?

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

The Federal Communications Commission had a hard job in front of it at the turn of the 21st Century. The group found itself wading through the complexities of taking analog television—something that nearly everyone had used for decades—and getting viewers to go digital.

That move was perhaps the most unusual case of planned obsolescence in the modern age, a decision, mandated by the Telecommunications Act of 1996 that forced hundreds of millions of people out of their usual routine.

Many folks weren’t ready, or maybe they didn’t care enough about their TV signal quality to upgrade. But nearly eight years ago, it happened anyway, and the United States finally threw out its old rabbit-ear antennas—no matter how much it hurt.

The effort started slowly, with a test conducted by 25 television stations on November 1, 1998, according to a FCC report on the formulation of digital TV technology. The feeds, based in the 10 largest television markets, were very limited at first. A 1998 CNN report noted that one of the first programs to show up in a digital format was a screening of 101 Dalmatians, which only people who owned $5,000 television sets (or bought adapters for their not-as-good screens) could afford to see in the high-quality format.

Mandated by law to see the change through, the commission often buckled to keep the transition on track, even as the prices of digital televisions went down from $5,000 to $150.

And the job was messy. Former FCC chair Michael Powell often found himself in the unenviable position of trying to clean up a massive, bureaucratic mess. As early as October of 2001, Powell had to set up a task force intended to fix the problems around the transition.

“The DTV transition is a massive and complex undertaking. Although I’m often asked what the FCC is going to do to ‘fix’ the DTV transition, I believe that a big part of the problem were the unrealistic expectations set by the 2006 target date for return of the analog spectrum,” Powell said in an October 2001 news release. “This Task Force will help us re-examine the assumptions on which the Commission based its DTV policies, and give us the ability to react and make necessary adjustments.”

And those adjustments kept happening. For years, the federal government passed regulations or legislation to kick the can down the road as many times as it could. In the midst of a major housing and financial crisis in late 2008 and early 2009, the Bush and Obama administrations repeatedly found themselves having to deal with one small piece of legislation or another related to the digital transition. At a time when things were going to hell in a handbasket, we couldn’t even rely on TV to be a source of comfort.

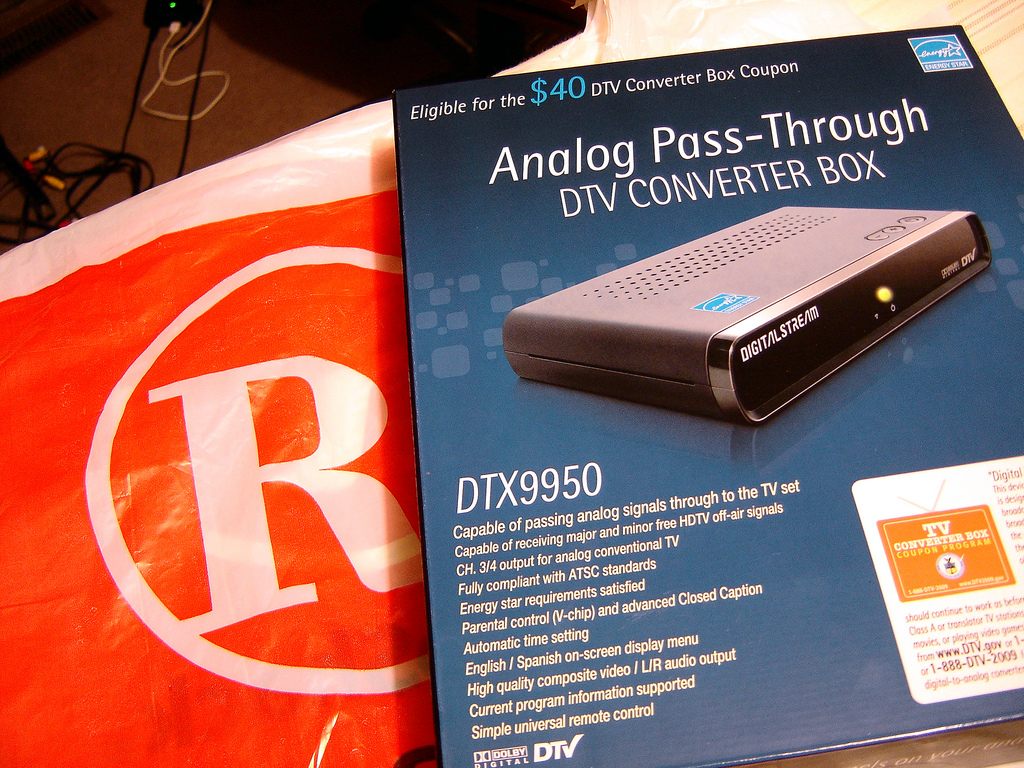

(It wasn’t cheap, either: The U.S. government earmarked $1.5 billion to the National Telecommunications and Information Administration as part of its program to allow Americans to buy $40 digital converters for their analog TV sets. Despite the more than $2 billion the government paid to ease the transition, millions weren’t ready, despite the fact it was widely promoted pretty much everywhere.)

In some ways, the United States probably wished it could’ve been first country to complete the transition to digital television—after all, we invented television.

But ultimately, the U.S. was too big, and the 2006 deadline too ambitious. The Scandinavians, with their smallish populations and high standards of living, had much better luck. Sweden, for example, completed the process in October 2007—two and a half months ahead of schedule. Nearby Norway, on the other hand, began its transition later than the U.S. did, but it only needed two years to move everyone over, finishing up in 2009.

In comparison, it took 11 years for the U.S. to shut off its analog TV stations for most uses. And some low-power stations—think TV stations run by high schools, or religious networks—only went to digital last September, nearly 16 years after the federal government began its switchover. (Even still, some analog stations persist, not as television stations but as FrankenFMs, radio stations that take advantage of the distance between analog channel 6 and the start of the FM radio dial.)

Still, for many stations, the move was historic. And several of them did all sorts of offbeat things to reflect.

In Mesa, Arizona, for example, KPNX-12 played up the transition to DTV, including the fact that it had hired a full-fledged call center to help local viewers, during a newscast that night. At one point during the newscast, anchor Mark Curtis told someone in the master control room to hit the switch, and … boom. Static.

In Dallas, WFAA brought a number of its old engineers to the station’s transmitter building to celebrate as the station shut off for the last time. A number of them had worked for the station for decades. On the analog signal, the station’s Pete Delkus briefly discussed the station’s history, and the clip included the station’s ‘70s-era signoff, which is friggin’ awesome.

Pittsburgh’s KDKA pulled out the poetry for the last moments of its analog broadcast—a short clip, featuring a U.S. Air Force pilot flying in mid-air while a voice was reciting High Flight, a famous sonnet by John Gillespie Magee, Jr., a pilot born in China, but whose father was a missionary from Pittsburgh.

New York’s WNBC played a montage of the NBC network’s many logos, ending with the slithery snake logo, before it transitioned to a blank black screen that says “goodbye.”

And, finally, Portland, Oregon’s KOIN re-ran a half-hour telecast of the station’s 25th anniversary special, which was originally created in 1978. Watch the first part here, then the second, and finally the sign-off.

But it wasn’t just the local networks reacting to the big change. The public often found itself trying to tackle the change, too. Sometimes, this came with a healthy dose of mistrust for government.

In the midst of the switchover, a guy named Adam Chronister trolled the Alex Jones crowd pretty hard by posting a video to YouTube that suggested there was a built-in microphone and camera inside of the digital converters.

“I was listening to the Alex Jones show … and I heard him mention the video. I just about fell out of the shower,” Chronister recalled to Wired.

Technical experts quickly figured out he was blowing smoke, but conspiracy theorists bought it—hook, line, and sinker. Chronister said the goal of the video was ultimately to fool a gullible friend.

“I originally opened up the device with the intention of proving him wrong,” Chronister told the magazine. “At which point the thought popped in my head, wouldn’t it be funny if I proved him right instead?”

But of all the weird things about the digital TV conversion, none, perhaps, was weirder than the transition period that occurred after the shutoff.

A while back, I noted there was a cottage industry of people who liked to create clips imagining what the end of TV would look like, in the case of nuclear war or similar disaster.

When analog television faced its death knell, no imagination was needed: People saw a former TV weatherman named Mike DiSerio doing what he does best—getting in front of a camera.

In most markets, an infomercial-style video starring DiSerio was aired to highlight the forthcoming switch. The videos, showing DiSerio, a couple of actors, and a wide array of onscreen messages in two languages, tried to communicate an important message to an audience living under a rock.

DiSerio’s role as calm, collected television doomsday soothsayer came about for two reasons: First, he worked for the National Association of Broadcasters, which played a key role in the transition; and second, Congress had passed a law at the tail end of the George W. Bush administration that called for a short-term continuation of analog TV signals for public service reasons.

The “analog nightlight,” as it was called, ensured that most markets would have a period where they saw Mike DiSerio enter their lives. The law passed quickly, and it took the FCC just days to codify new regulations in January of 2009.

Different TV stations aired the nightlight programming at different times, often relying on different strategies. Larger stations, given the go-ahead by Congress to extend their analog-transition period until June of 2009, stayed on the air with both analog and digital signals until then, only airing nightlight programming after that point. Smaller TV stations, however, didn’t have the budget to delay the switch any longer; they turned off their analog feeds in February. TV stations in cash-strapped markets couldn’t even afford to put DiSerio’s polished message on the air at all.

Despite the hard work that went into the process of the analog switchover—and DiSerio’s considerable charms—as of June 2009, Nielsen estimated that 2.8 million homes still hadn’t made the switchover to digital.

Maybe it was intentional?

The switch from analog to digital is, at this point, well-established in the U.S. and many other countries.

(But not all: Ukraine, beset by diplomatic struggles, delayed its transition earlier this year. “It is obvious that Ukraine is not yet ready to go digital, but if we constantly postpone the decision with the company Zeonbud, we will never move to digital, and will always be dependent,” noted Yuriy Stets, the Ukranian Minister of Information.)

It may be one of the hardest things that the federal bureaucracy in the United States has ever had to do, but for the most part, it worked. Problem is, broadcast TV isn’t as appealing as it once was. Much of the population is already moving on to greener pastures, throwing shows on Rokus and Apple TVs, and moving past broadcast television entirely.

But still, some complain. Five years ago, someone named Jesse Hakinson posted a call to action on a website called Petition 2 Congress, asking that Congress repeal the analog TV switch. Yes, someone wants to repeal the incredibly expensive endeavor that cost individual television stations thousands of dollars, and forced the federal government to spend billions in taxpayer dollars just to get the analog-to-digital converters into homes around the country.

“Sure, it’s only been two years, but it’s been long enough,” Hakinson wrote. “It’s time to help the lower class again.”

This petition, despite the fact that it has literally no chance of going anywhere, and despite the fact that the wireless spectrum that analog television used is already in the process of being auctioned off to help feed our smartphones, still gets new signatures constantly, with people annoyed by antenna problems using the forum to vent.

The petition is the digital equivalent of TV static.

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook