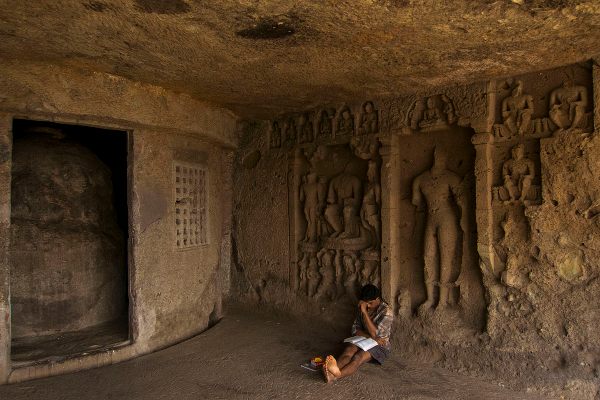

Inside the Hidden Natural History Museum of Mumbai

Rahul Khot oversees 138,000 specimens at the Bombay Natural History Society.

In the week before India went into its three-month coronavirus lockdown, Rahul Khot was a busy man. The curator of the wildlife collection at the Bombay Natural History Society in Mumbai, Khot was working to ensure that the nearly 138,000 specimens under his care would be okay without regular supervision. “We weren’t really worried because we have foolproof practices,” he says. Still, he wanted to be prepared.

Khot’s team checked that the specimens were properly stored and that chemicals were replenished wherever needed. During the lockdown, when residents of India were unable to travel, Khot would get on video calls with security personnel and ask them to walk through the collection, to check for rats or leaking taps, and to open windows to air out fumes from the preservation chemicals. “This is probably the first time in the last 137-odd years of BNHS that we’ve been closed for three months,” Khot says.

The Bombay Natural History Society, established in 1883, is a nationwide nonprofit dedicated to conservation, environmental research, and education. The group is well-known for its awareness campaigns, field research, advocacy, and nature trails. What’s less well-known is that BNHS runs a hidden museum where specimens, collected from across the Indian subcontinent, sit in cupboards, storage units, and special rooms in the society’s headquarters. Opening doors and drawers brings one face-to-face with perfectly preserved blood pheasants, moon moths, pangolins, and jars filled with cobras and gliding frogs.

Researchers are well aware of the society’s wildlife wonders, but many members of the general public don’t know that they can request a guided tour of the collection for less than two U.S. dollars. Khot is working to make the collection more accessible, both in-person and online. He spoke to Atlas Obscura about his dreams for the museum’s future, how he became a caretaker for a massive scientific collection, and how to preserve everything from insects to fish.

Why is this a significant collection?

This is the second-oldest collection in India. (The first, I think, is the Indian Museum in Kolkata.) Our collection is a snapshot of the rich biodiversity of the Indian sub-region. We have specimens that came from today’s Afghanistan, Pakistan, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, and even Iraq and Iran. In colonial times, many British officers were avid naturalists—they would collect creatures and donate them for research purposes. That’s how the collection started. We have 140-year-old specimens, like a whiskered tern from Myanmar, collected in 1886, and a hyena from the Somali coast, collected in 1881. There are even some extinct species like the pink-headed duck.

What sort of qualifications does it take to become the caretaker of more than 100,000 specimens?

You need to love this kind of work—dealing with specimens is a specialized job. You have to make sure they will be there for hundreds of years.

I joined BNHS as a research assistant in the collection department in 2009. You must have at least a master’s degree in zoology to get into the field. Once you’re in, you have to learn the techniques of collecting specimens with proper government permissions, and of preparing, preserving, and storing them, as well as handling and disposing of chemicals.

Then there is the management of the museum. Our museum differs from other ones where the public can freely examine exhibits. Here, you have to give people easy access to the collection. Sometimes researchers may not be able to come in person, and ask you for information: measurements, observations, photographs. So you have to be tech-savvy.

Lastly, there is outreach. We are the custodians of these specimens, and we welcome everyone. Today, about 1,500 people visit the collection annually, many of them from schools and colleges. Generally we take a batch of 40 to 50 people and host a two-hour educational program that requires you to be a good orator, manager, and researcher. Basically, you need to be a jack of all trades.

What keeps you motivated in such a challenging job?

We see things that many are not privileged to see. Often, researchers come by and discuss their work and current trends. People outside the science community contact us with queries all the time. Sometimes, they send us photos and ask for help in identifying a species.

The most inspiring thing is there’s always something new. Each drawer and each specimen is like an unread book.

In your opinion, what makes a good natural history collection?

Having a natural history museum in any form is a good thing. What makes it better is its staff, the preservation practices, and the record-keeping methods. If the specimen has no information it may not be very useful—I don’t know the origin, who collected it, when it was collected. The most important thing for a collection like ours is access. Researchers should be able to easily see the specimens and related data.

How do you decide to add a specimen to the collection? What are the criteria it must fulfill?

You need proper permission from relevant government authorities when collecting specimens. If you are a researcher and want to collect something to study further, then you apply to the Forest Department for permission to collect it, and then give it to a museum like BNHS. Our in-house researchers also contribute to the collection. Sometimes we receive rare and unique specimens from the Forest Department. A few years ago, we got a snow leopard skin from officials in the state of Sikkim.

There’s three crucial bits of data that every specimen must have: date of collection, locality, and name of the collector. Nowadays, we also ask for the geocoordinates, the methods of collection, and the preservatives used.

Do you remove specimens from the collection?

Never. Removal is out of the question.

How has the pandemic changed your job?

We have sanitizers at every corner, people now wear masks, and we check temperatures at the entrance to the building. With regards to public programs, we will follow government orders. But it won’t affect how we deal with specimens. We already wear masks and gloves while handling them, to avoid exposure and direct contact inhalation of the preservation chemicals.

What does it take to preserve the specimens in such good condition?

Our dry specimens are kept in regular cupboards—birds and mammals in steel cabinets, insects in chests of drawers. There are set international protocols for preserving a specimen. We have to catch and euthanize it properly, ensuring minimum damage to the creature. Insects are stretched in a proper position and then put in an oven between 55 to 75 degree Celsius for a few days, to dry. This is necessary to remove the moisture that is responsible for the postmortal degradation. Lastly, a label is added with the relevant data.

The principles of taxidermy apply to birds and mammals. We remove all the bones and organs after dissecting them from the belly. In birds, half the skull is kept intact because the beak is connected to it. For mammals, we remove the entire skull. It is cleaned and kept with the specimen, because mammal taxonomy depends on the skull and dental structures. The specimens are then treated with different chemicals, stuffed with material like cotton, and measured to ensure that the final specimen matches the original.

The process is different for wet specimens, which are subjected to a formalin treatment that increases shelf life. After that, we wash them in pure water and put them in alcohol solutions with increasing concentrations, from 10 percent to 70 percent, washing them with water in between each solution change. That gradually increases the alcohol content in the body without any damage to the cells. These specimens are kept in a fire-proof room with separate ventilation and fire-proof doors and ceiling. We have six heavy-duty fire-rated cabinets, each weighing around half a metric ton. It’s basically a safe that can withstand temperatures of 3,000 degree Celsius for three hours. We keep rare wet and dry specimens in there, as well as type specimens, which are the origin specimens on which the description of that species is based.

What is the one species that you want to include but haven’t been able to yet?

It’s a long list. Marine mammals would be interesting. We have a good collection of marine invertebrates like sea slugs, crustaceans and flatworms. But you have to think about the space constraints for large specimens. Instead of putting an entire rhino or elephant in a cupboard, I can fit hundreds of bats or small mammals in the same area.

We have about 750 butterfly species out of the 1,500 found in India. As an entomologist I would like to see more but, of course, that may not happen. In the last few years, we collected about 800 specimens of arachnids and more than 1,000 endemic fresh-water fish specimens, including many newly described species.

What kind of reactions do you get from the public?

The questions depend on the audience. The kids often ask us if the specimens are real, and enjoy seeing the colorful butterflies the most. Government officers and trainees ask about legalities around protected species and what procedures to follow in specific situations. We try to highlight how ecosystems work, their importance, and why we should conserve them.

A lot of researchers know about the existence of this collection, but it’s relatively hidden from public view. Was that intentional, and could it change in the future?

The focus here will remain on academics and research. But we are coming up with a new center in central India, near Nagpur. There will be labs, museums, and research facilities. Since there will be more space, maybe we can have more public viewing. I’ve noticed how museums in other countries have integrated facilities, combining research labs and exhibits. Visitors get a chance to see displays and also what’s happening in labs through glass windows. Perhaps we could have something like that.

The immediate next step is digitization of our collection, which we hope to complete in a few years. Soon, people can just search by name, species, or date.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook