The First Democratic Convention on Live TV Was the Last Not to be Air-Conditioned

In Philadelphia in 1948, it got hot.

The 1948 presidential campaign, which would later result in one of the most famously wrong newspaper headlines in American history, was complicated. For the first time ever, three candidates—Democrat Harry Truman, Republican Thomas Dewey, and Progressive Henry Wallace—were nominated at conventions in the same city: Philadelphia.

Philly, of course, is also hosting this year’s Democratic National Convention, for reasons that have a lot to do with Democrats’ attempts to win Pennsylvania in the fall, and less to do with simple logistics. But in 1948, for both Democrats and Republicans, Philadelphia was a choice that was mostly about logistics: the logistics of getting on television, to be specific.

That’s because Philly sat on top of a television coaxial cable that gave each party access to millions of eyeballs—TV-watching eyeballs—using a then-novel technology that both sides were trying to exploit. And while tens of millions more listened along with their radios—TV would not truly define a presidential election until 1960—there, for the first time, live on television, was the future of our nation, broadcast for all to watch.

And while American political conventions have always been gaudy spectacles of tastelessness, this was also the first time many Americans laid eyes on the raw show itself, which some commentators then predicted would lead conventions to tone down the madness. It was just all too classless and undignified, you see.

“Many viewers indicated that they found the recurrent carnival spirit not in keeping with the dignity they felt should prevail in the business of selecting a presidential nominee,” a New York Times columnist wrote, going on to predict that television would force the political parties to “pare away bombast and high jinks associated up to now with [conventions].”

If only. Still, the 1948 conventions made history, even if, by today’s numbers, the amount of viewers remained small. The U.S. population was less than half the size it is today, or around 148 million people, but just a small fraction of those—up to 10 million—are thought to have watched, primarily because the broadcasts were only available along the Eastern Seaboard, from Boston to Richmond. (Coaxial cables in 1948 only went so far.)

So, what, exactly, did viewers see? A lot of sweat, for one thing. The Philadelphia conventions that year were the last time political conventions were held in a venue that didn’t have air-conditioning. And in video of Truman’s speech at the convention, convention-goers are seen getting creative in how they fanned themselves, many using what appeared to be programs, mostly in vain.

On stage, things were considerably worse, mostly because of the lights. If the convention was to be televised, networks told convention organizers, the dais would need to be lit up. And, because of the primitive camera technology of 1948, that meant highly lit up. As a consequence, convention speakers, many of whom could be seen with visible sweat stains, probably had it the worst of anyone. (Their wives, sitting behind them, didn’t have it much better.)

The Republicans were the first into the spotlights, arriving in late June and assembling at the now-demolished Convention Hall. There, the heat and lights were omnipresent, but so was something else that would become a staple of TV: makeup. Public figures were still figuring out their makeup game, or how to look good both in person and to the viewers at home. Dewey, for example, brought his own, but still fared poorly, thanks to his beard complicating things. Others simply refused to wear makeup, opting to go natural. But no one got it worse than Clare Boothe Luce, the wife of publishing magnate Henry Luce and a former congresswoman, who was scorned for her look on TV.

“Newspapers reported Clare Booth Luce looked fine in the hall, but terrible on television,” Reuven Frank, a former president of NBC News, wrote in 1988, while one syndicated columnist “expressed horror at what the cameras did to Mrs. Luce.”

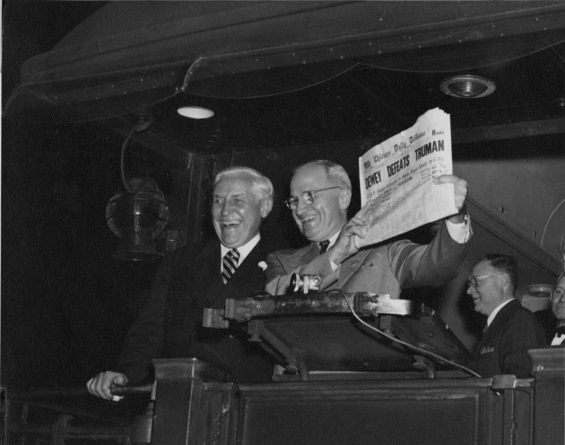

Truman with the famous headline. (Photo: Public domain)

At the Democratic convention, which began a few weeks later, the issues were similar. There was the heat of 15,000 bodies packed into one steamy hall, and there was the makeup, who would wear it and who wouldn’t. And there were even a lot of doves, thanks to a convention-goer who had set them loose in the convention hall.

Perhaps pushed along by the heat or the fact that it was televised, not long after the convention started something rare in modern conventions also emerged: true conflict. The party had narrowly voted to add a civil rights plank to their platform, the first for any Democratic party ever, which prompted, live on television, many southern Democrats to simply walk out.

This, for Truman, was a disaster, and dimmed his chances at the election in November. Still, on July 14, the convention’s final day, he roused himself to deliver a defiant 24-minute call to arms, taking to the rostrum around two in the morning, yet hardly seeming fazed by the heat, or the hour, or the moment.

And later that year, when no one remembered the heat, or the doves, or the makeup, Truman, in fact, won, beating Dewey in an upset.

That day, Truman hoisted up the Chicago Daily Tribune’s infamous front page, which trumpeted ”Dewey Defeats Truman”.

“Ain’t the way I heard it!” he said then, beaming.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook