The Bankrupt Irishman Who Created the Dollar Sign by Accident

Wars cost money. So when the Revolutionary War broke out, the Colonies turned to a number of sources for backing. The top contributors to America’s Independence: The Kingdoms of France and Spain, the Dutch banking conglomerate, and a single Irish merchant based in New Orleans. His name was Oliver Pollock, and he was the “Financier of the Revolution in the West.”

Pollock saw opportunity in war– the chance for a young but wealthy immigrant to stand as a symbol of success and greatness. He desired to carve out a place for himself in America’s financial landscape and perhaps even leave a mark in the nation’s history. He achieved all those things. Just not in the way he expected.

America was a British colony in revolt, so the preferred currency became the Spanish dollar, also known as Spanish peso, which was commonly obtained through illicit trade in the Spanish Caribbean. This was the exact manner of trade in which Oliver Pollock made his fortune. Pollock reached into his own deep pockets and made available to the American war cause 300,000 Spanish pesos. That amount is valued at roughly one billion dollars in today’s currency.

It was a massive sum, even for someone as wealthy as Pollock, but he gladly parted with it in order to back the revolution. After all, Pollock was Irish, and he believed that fighting Britain was his duty. As important as it was to root for the right horse, Pollock was still a businessman; he believed a sizable investment in the Revolution would pay dividends in the long run–and give him access to some of the most famous names in America.

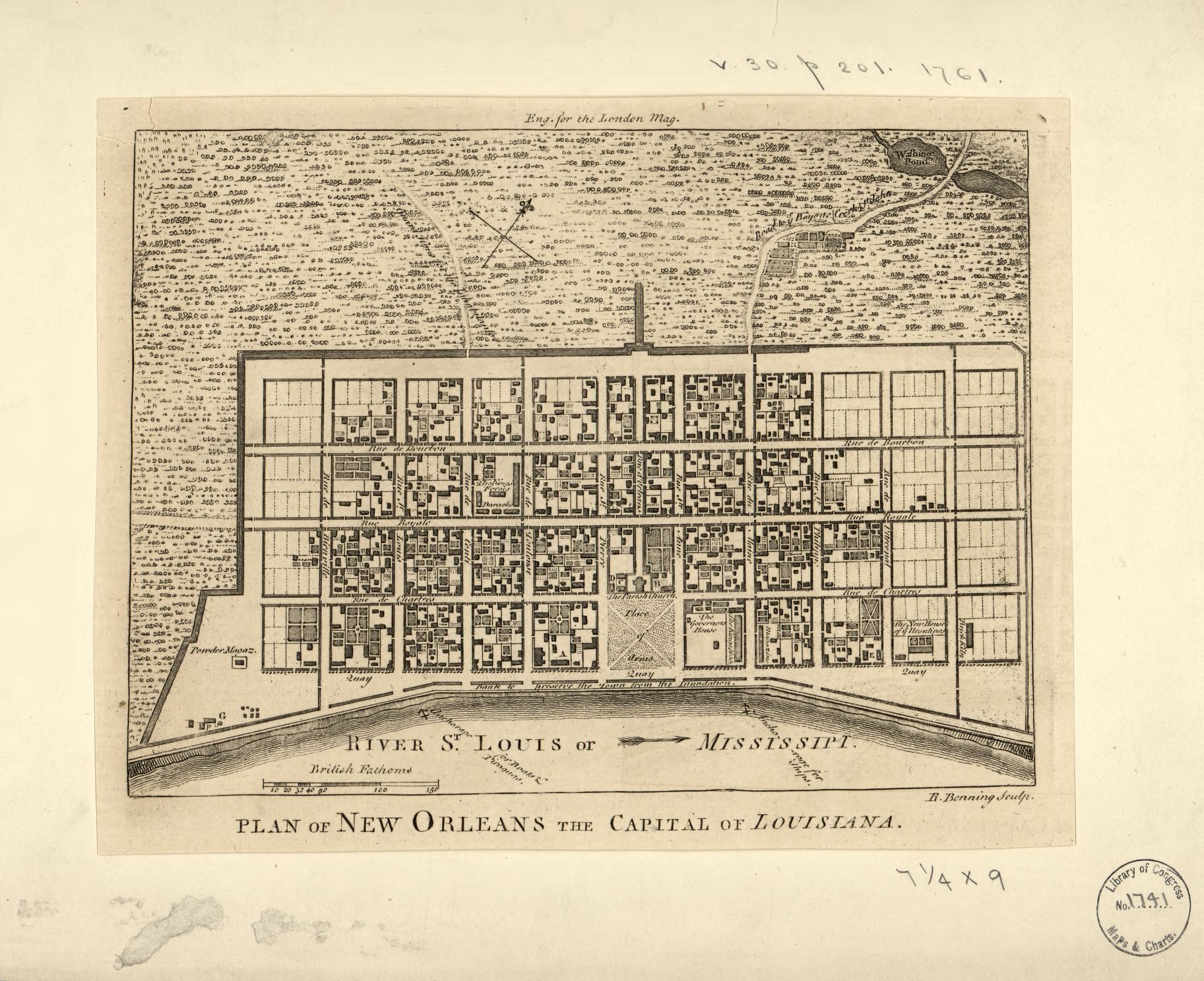

A 1761 plan for New Orleans, where Oliver Pollock worked as a merchant. (Photo: Library of Congress)

The primary beneficiary of Pollock’s finances was General George Rogers Clark, whose successful campaigns across the American frontier and especially in Illinois opened up the Northwest for the Colonial forces. In fact, James Alton James, the author of the sole book written about Pollock, Oliver Pollock: The Life and Times of an Unknown Patriot, argues that “the accomplishments of Clark [were] impossible without the contributions of Pollock.”

The Irishman followed his financial contribution with a diplomatic one. The American cause was believed too idealistic by some potential allies, while others saw Washington’s early struggles on the battlefield as a harbinger of Britain’s inevitable victory. Oliver Pollock refused to let these minor concerns get in the way of his financial windfall. Having been named the official representative of the Colonies in New Orleans by the Continental Congress, Pollock took it upon himself to approach “neutral” individuals on their behalf, providing support however needed.

When it came time to launch a crucial campaign against the British military in the South to prevent them from encircling the American rebels and keeping open a vital conduit for supplies, Oliver Pollock approached the skeptical Spanish Colonel and Governor of Louisiana Bernardo de Gálvez. Pollock personally convinced Governor Gálvez of General Washington’s ability to win this war and then sweetened the pot by personally raising the troops and supplies Governor Gálvez used to capture British forts in Louisiana, Alabama, Mississippi and Florida. The campaign was a massive success. It was also a huge drain on Pollock’s personal fortune.

A view of Havana, 1765, where Oliver Pollack was headquartered after leaving Pennsylvania. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Pollock had to find another way to raise money for the revolutionary effort: so he drew up bills of exchange, or war bonds, to sell to supporters of the colonies. When Pollock reached out to the Founding Fathers to support his new plan, they had no problem backing their man in New Orleans. “Investors were willing to purchase because of the public support given Pollock by Thomas Jefferson, who then served as Governor of Virginia,” explains Light Townsend Cummins in his paper “Oliver Pollock and George Rogers Clarks’ Service of Supply: A Case Study in Financial Disaster.”

The “Financial Disaster” part ofthe aforementioned title gives away what happened next–Oliver Pollock went broke. The expensive cost of raising of armies and supplies left him with nothing. To make matters worse, as a result of some favorable re-negotiating on the bills of exchange he had issued, he was made liable for them, as opposed to the merchant companies and the state congresses who originally backed them.

His creditors came looking for repayment. Pollock had no choice but to turn to his Northern friends for help. “Letters from Pollock…were read on the floor of Congress, and the Commercial Committee resolved that the U.S. Treasury should pay Pollock more than twenty thousand dollars…” writes Kathleen DuVal, in Independence Lost: Lives on the Edge of the American Revolution. But neither Congress or the state of Virginia had twenty thousand dollars to spare.

Illustration of George Rogers Clark’s march to Vincennes in the American Revolutionary War, 1779. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

More accurately, they didn’t have twenty thousand dollars for Oliver Pollock. At least not at that time. America’s coffers were earmarked for nation-building and unfortunately for Pollock, he had accrued his massive debt supporting the American cause in the West and the South–territory that was then handed over to France and Spain for their support during the War. Oliver Pollock backed the right horse. It just didn’t pay off.

Ironically, said nation-building did include Secretary of Finance Alexander Hamilton’s plan to establish a strong central bank and currency. Washington’s Superintendent of Finance, and Pollock’s close friend and business partner, Robert Morris–himself a key financial backer of the Revolution–began the process by sifting through the countless ledgers sent to Congress by Pollock, who, per Dr. Cummins,“kept careful record of these amounts, noting both the Bills which he received and the supplies which he purchased.”

It was with those ledgers that Oliver Pollock finally achieved his dream of providing America with an important, lasting contribution. Not the numbers, but the poor penmanship that accompanied them.

“Pollock…entered the abbreviation ‘ps’ by the figures for ‘peso.’ Because Pollock recorded these Spanish “dollars” or “pesos” as ‘ps” and because he tended to run both letters together, the resulting symbol resembled a ‘$,’” says Jim Woodrick, the Historic Preservation Division Director of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

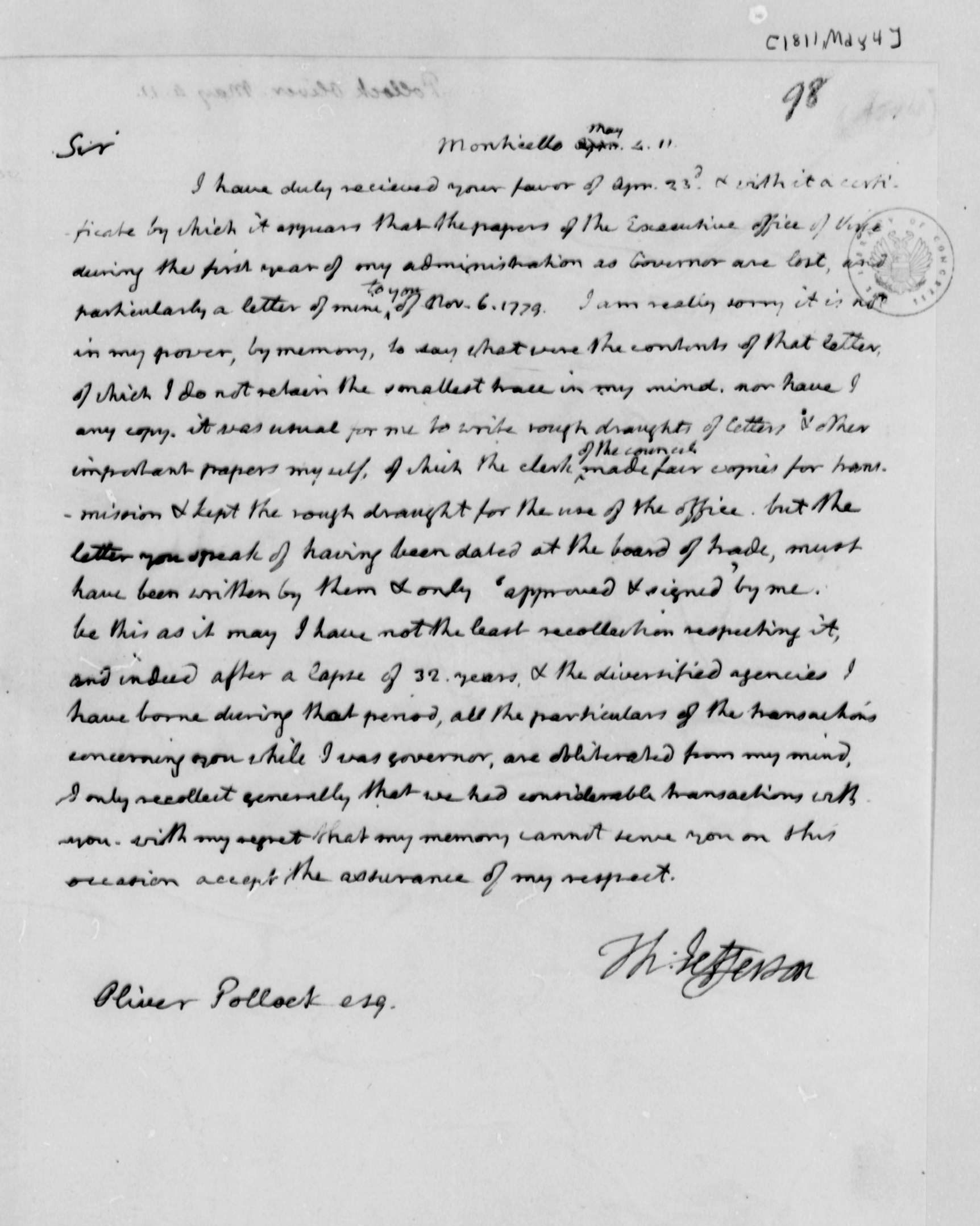

Jefferson’s letter to Pollock, May 4, 1811: “all the particulars of the transactions concerning you while I was governor, are obliterated from my mind..” (Photo: Library of Congress)

That’s it. Historians have analyzed the source of the $ symbol and have yet to find it written down prior to Pollock’s use in his ledgers. His unintentional creation is supported by the fact that Robert Morris chose to adopt the symbol and by 1797 had it cast in type in Philadelphia as the official symbol for new nation’s own currency.

Meanwhile, Oliver Pollock did the only thing he could do. He declared bankruptcy in early 1782 and liquidated his assets and personal possessions. This included the Mississippi River lands near Baton Rouge and Pointe Coupée upon which Louisiana State University would be built.

Pollock thought he had caught another break in 1783 when he was appointed an agent of the United States in Havana, but that backfired when his Cuban creditors decided he owed them $150,000. He spent more than a year languishing in a Havana debtors prison until he was bailed out by his old war buddy Governor Gálvez.

Pollock returned to the U.S. in 1785 and continued his attempts to regain his wealth and stature. His efforts to do so are best illustrated by the missive he received from his old friend Thomas Jefferson in 1811: “All the particulars of the transactions concerning you while I was governor, are obliterated from my mind, I only recollect generally that we had considerable transactions with you,” wrote Jefferson in May of that year.

Just as swiftly as he found himself among the upper echelon of American revolutionaries, Pollock disappeared from their ranks, becoming only a footnote in their successful quest for independence from Britain.

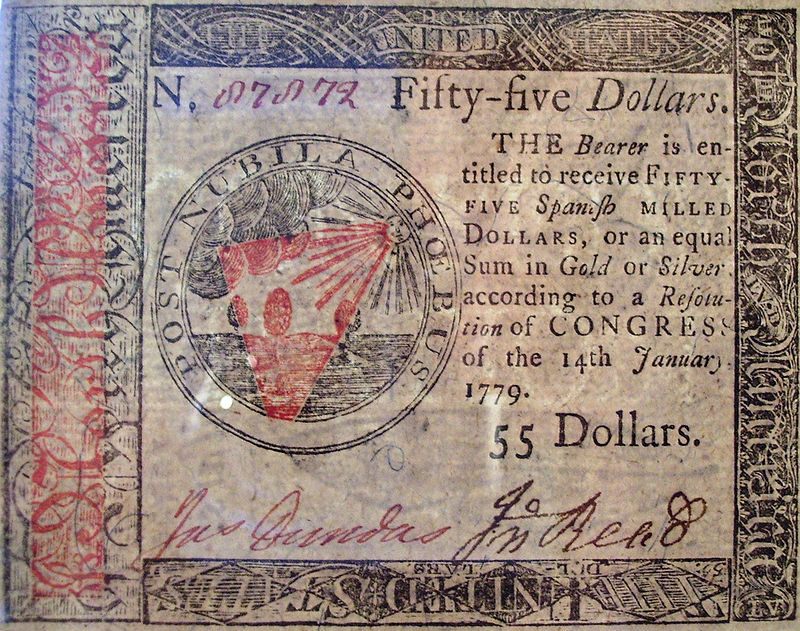

Fifty-five dollars issued in 1779. (Photo: Beyond My Ken/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

It wasn’t until 1791 when Congress finally discharged Pollock of his debts. He moved to Cumberland county, an Irish immigrant enclave in Pennsylvania, where he ran for Congress –and lost–three times. When his second wife died in 1820, he went to live with one of his daughters, who had married a plantation owner in Pinckneyville, Mississippi, which is where he died in 1823.

In one final ignominy to his memory, a gunboat shelled the property during the Civil War and all of his personal effects were destroyed in the ensuing fire. All that remains of him is a single gravestone in the defunct Pinckneyville Episcopal Church cemetery, which his sole depiction in the U.S. is an impressionistic bronze sculpture on display since 1979 in Galvez Plaza in downtown Baton Rouge.

Oliver Pollock is proof that while money can buy many things–from victorious armies to powerful connections–it can’t guarantee what sometimes happens by accident: a legacy.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook