The 19th-Century Black-Owned Pottery That Changed American Ceramics Forever

H. Wilson & Company, founded by a group of formerly enslaved potters, made an indelible mark on American craft—and American branding, too.

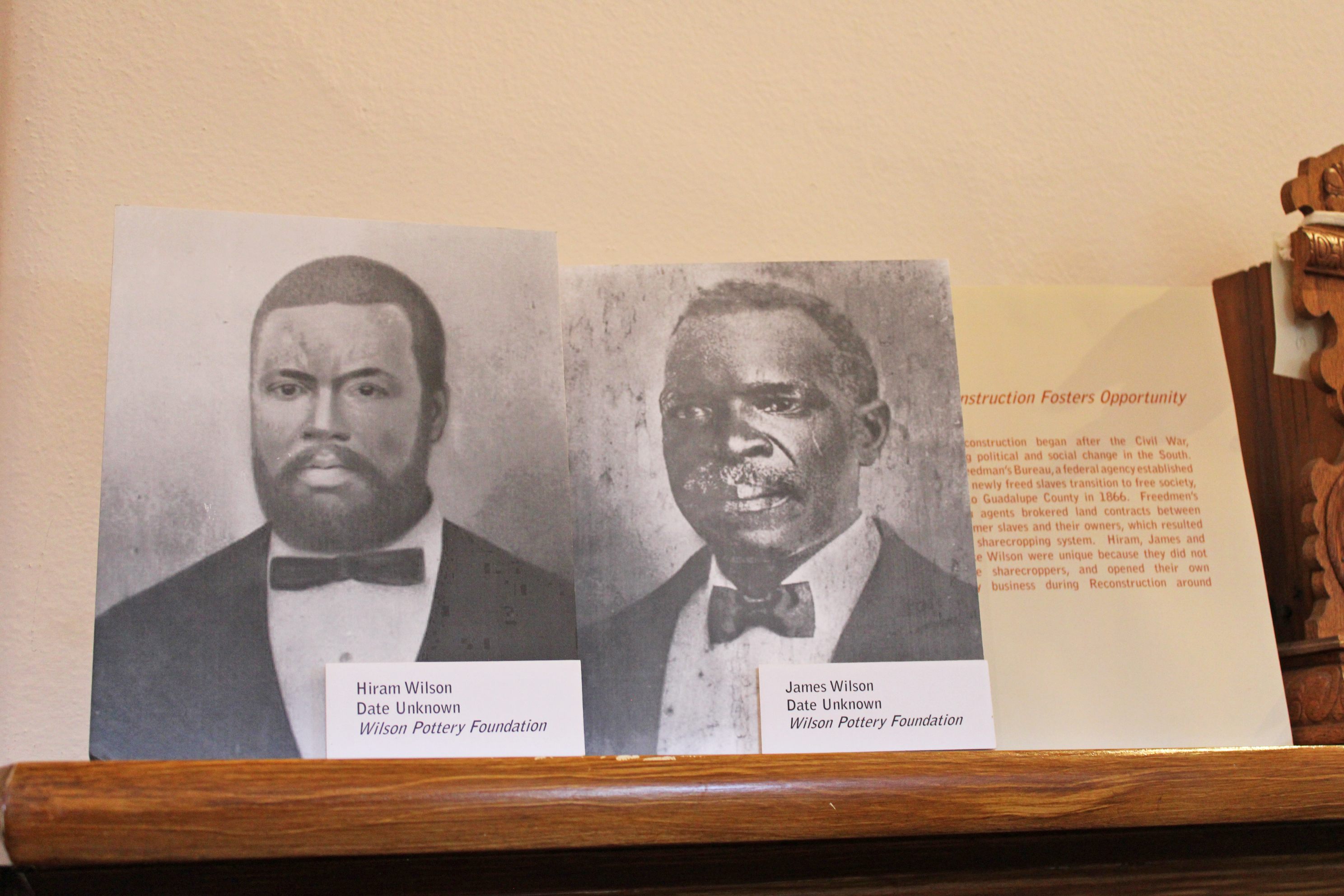

In 1869, a formerly enslaved man named Hiram Wilson did something remarkable: Along with several other Freedmen who’d been brought to Texas as slaves by the Presbyterian minister John McKamie Wilson over a decade prior, he formed what is widely considered Texas’ first Black-owned business.

The men had arrived in Guadalupe County eight years before the end of the Civil War, roughly a decade before a Union general announced news of the Emancipation Proclamation to the people of Galveston. Upon their arrival, they’d been labored in the business the Reverend Wilson took up after arriving in Texas—a pottery, which produced alkaline-glazed and salt-glazed stoneware. Like other enslaved potters working throughout the south, Hiram and the other men grew incredibly skilled in the craft. Hiram even managed parts of the enterprise when the Reverend could not. Following the men’s manumission, they went into business under the name H. Wilson & Company, having taken on their former enslaver’s surname as was customary at the time.

The Wilsons quickly transferred the skills they’d learned into maximizing the products of their labor. “Hiram was more than just a potter. He was an industrialist—he used salt glaze to turn out a great deal of pots at a time,” says Robert Gray, a historic site guide at Seguin’s Sebastopol House, where many works from the Wilson Pottery Foundation are on display. “Salt glaze is thrown in a kiln, so you do however many pots can fit in a kiln—a hundred, a couple hundred. He was really turning them out.”

This speed and efficiency was not the Wilsons’ only technical innovation. They also created an altogether new style of pottery, diverging from the techniques they’d been taught while enslaved. They formed their wares with horseshoe-shaped handles, which were closer to the pots themselves than the older cup-shaped varieties (and therefore much less likely to break off). Fashioning a rim atop each jar provided a space for their lids to sit securely, a design that better preserved food and greatly improved upon the tie-down tops that could easily grow loose and cause unwanted spillage.

Perhaps the most surprising change the potters of H. Wilson & Company made to their work in the late 19th century may sound like a commonplace business detail now: they marked them with the company name. “A lot of people don’t understand how significant that was,” Gray says. “That was branding; there wasn’t branding at the time, [except among companies] like Nabisco and General Mills cereals.”

Unlike the nascent branding at large industrial operations, the H. Wilson & Co signature communicated something beyond promotion or commercial ownership. When the Wilsons marked their works, they transformed each piece into a testament of their labor, artistry, and determination. They imbued their work with the ability to convey the resilience and ingenuity of newly freed Black people in Texas and beyond—Wilson vessels reportedly traveled throughout the south, and as far west as California. That affirmation of Black craftsmanship, perhaps more than even the substantive tactile modernizations they pioneered, made the Wilsons a foundational influence in 19th century pottery.

Hiram Wilson ran his pottery until he died in 1884, at the age of 48. By then, he’d also amassed a staggering array of accomplishments. He’d gone to college, become a Baptist minister, started several schools, and purchased over 6,000 acres of land to be divided among recently emancipated families.

The identifiers on the Wilson wares are part of what made it possible for LaVerne Lewis Britt, who traces her lineage back to the Wilson potters, to recognize the stunning contributions her ancestors had made to their community—and to the craft of pottery throughout the whole region. In 2005, a few years after some of the Wilsons’ descendants formed the Wilson Pottery Foundation, Britt published a book about her great-grandfather, In Praise of Hiram Wilson: The Story of a 19th Century Guadalupe County Potter. “We feel it isn’t just our legacy, but everyone’s in Texas,” Britt told MySanAntonio in 2011. “And we want to share it with everyone.”

Now, many of the Wilsons’ works are on view at the Seguin-Guadalupe Heritage Museum, as well as the Wilson Pottery Museum located in Sebastopol House, which also showcases the many tools that enslaved people used to construct the site itself prior to Emancipation. Prior to the onset of the pandemic, the Wilson Pottery Museum also hosted an annual pottery show in the fall.

The Sebastopol House Historic Site will be hosting a pottery show on October 29, 2022, in conjunction with Seguin’s Pecan Fest.

This post is sponsored by Visit Seguin. Click here to explore more.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook