Long Before the First Thanksgiving, an Artificial Island in Florida Hosted a Cross-Cultural Feast

Decades before the Wampanoag and Pilgrims shared a meal, the powerful Calusa and their Spanish guests celebrated their new alliance. Spoiler alert: It didn’t last.

In 1521, Spanish conquistador Juan Ponce de León sailed his ship up the southwest coast of what is now Florida. He was looking to start a colony there, but when he and his men came ashore, Calusa warriors met them with shark-tooth war clubs and arrows and spears that were tipped with pointed bone and fish spines. An arrow landed in Ponce de León’s thigh, eventually killing him.

That pretty much kept the Europeans from bothering the Calusa for the next two centuries, except for a brief period of cordial relations, beginning in 1566. That was the year King Caalus hosted the governor of La Florida, Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, at a lavish event. Decades before the first “Thanksgiving” in Massachusetts, it was the second-earliest recorded meal to bring Native Americans and Europeans to the same table, and occurred just six months after the first, when Menéndez founded the town of St. Augustine on Seloy tribal lands. The feast shared by the Calusa and the Spanish is noteworthy for another reason: It included one of the earliest guitar performances on American soil.

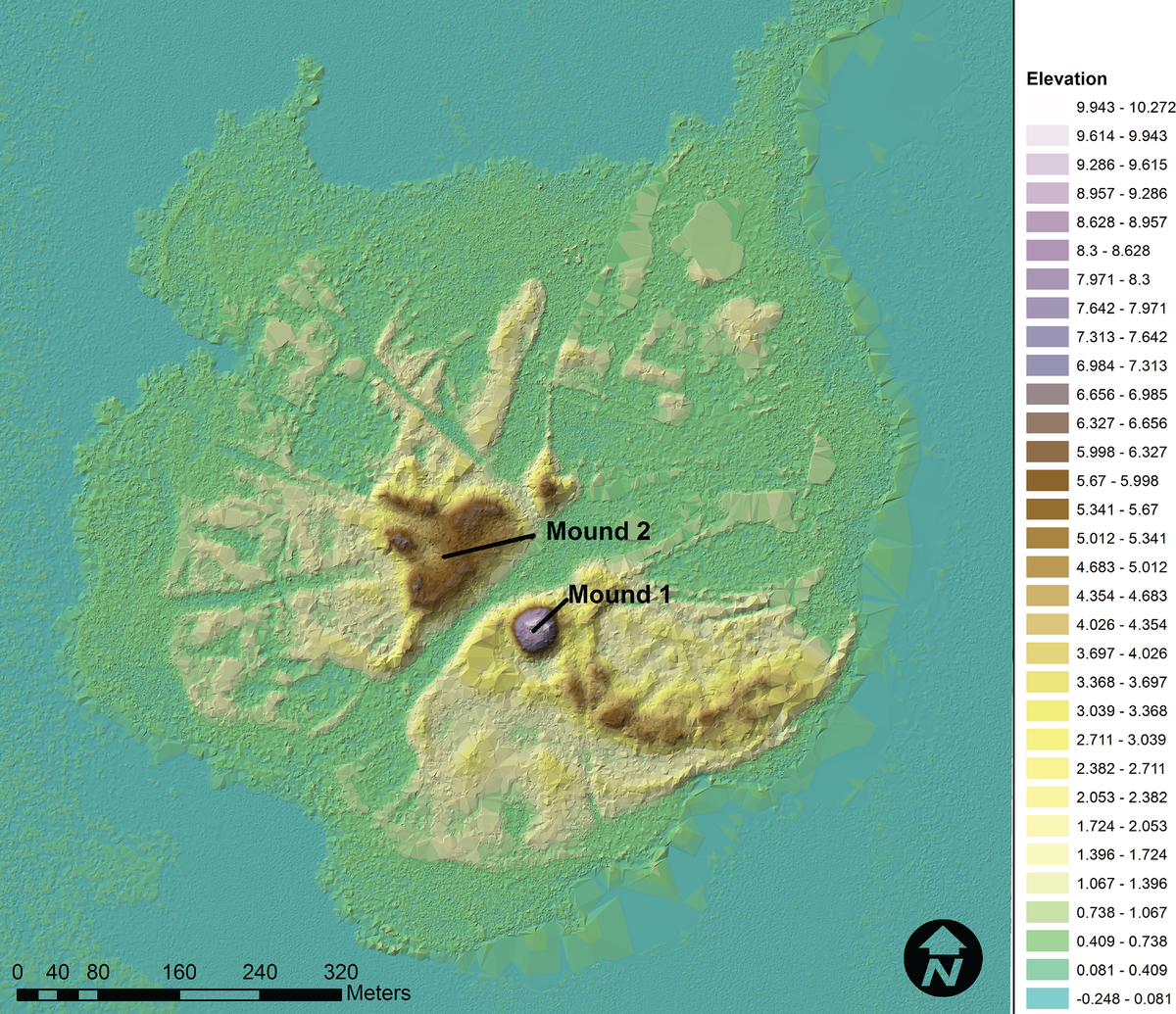

The event took place on the summit of an artificial island near present-day Fort Myers. Today it’s the archaeological site of Mound Key, but back then it was the seat of the powerful Calusa kingdom. That night, the Calusa and their guests dined in a grand hall built from wood with a thatched roof; it was large enough to fit 2,000 people. More than a meal, the event was a political summit, complete with speeches, gifts, the betrothal of King Caalus’s sister to Menéndez, and plans for an alliance that would lead to both a Spanish fort and mission on Mound Key.

The Calusa served up fish and oysters while the Spanish arrived with 100 pounds of biscuits, wine, molasses, and quince jelly. Looking to impress, the Europeans also brought an entourage of hundreds, including soldiers and musicians, as well as tablecloths and napkins.

The Spanish likely thought the linens might “civilize” the affair, but the Calusa were already quite sophisticated. In addition to smaller communities up and down the coast, about 4,000 people lived on and around Mound Key, a complex urban center that was on par with contemporary Aztec city-states. Mound Key, covering more than 125 acres, was itself created by the Calusa and has withstood at least a thousand years of storms. The island was built by layering shells, bones, and other material. It featured a network of canals, smaller mounds, and “water courts,” areas to raise and store live fish and shellfish.

“It’s not like a small village where every household makes their own pots and gets their own firewood,” says archaeologist Victor Thompson, who has studied the Calusa city-state for more than a decade. “There had to be an economy with a distribution of products. With urbanism, you have to engineer for public works like waste disposal, fresh water, and public transportation.”

The Calusa were in fact one of the most powerful political forces in Florida, with influence that extended from south of Tampa Bay to the Florida Keys. And what’s more impressive is that they did it all without agriculture, one of the only complex urban societies to do so, an accomplishment detailed by Thompson in a new paper published in the Journal of Anthropological Archaeology.

Thompson and fellow archaeologist Amanda Roberts Thompson, his wife, codirect the University of Georgia’s Laboratory of Archaeology. In 2017, they were part of a research team that definitively located the remains of the grand hall on Mound Key. Victor Thompson describes the scope of the Calusa capital as “mind-boggling,” and “one of the most well-preserved examples of Indigenous architecture in the southeastern United States.” But the story he’s most excited about actually concerns Menéndez’s musical diplomacy.

According to historical records, on the night of the feast, Spanish musicians played fifes, drums, trumpets, a harp, and a guitar. The Calusa reportedly loved the music, and it helped the two cultures bond. Imagining the guitar performance in particular delights Thompson, a guitarist himself: “I just love thinking about some Jimi Hendrix of the 16th century sitting there at the feast, [playing] this fantastic instrument that gives me so much joy.”

Unfortunately, and perhaps predictably, the alliance between the Calusa and the Spanish didn’t last. Within a year, the arrangement fell apart and King Caalus’s sister, who had been baptized as Antonia, returned to Mound Key. The Spanish assassinated Caalus in 1567, and also killed his successor, Felipe, in 1569.

“By that point, everyone’s like, ‘This is terrible. Let’s just burn the village and drive out the Spanish.’ And that’s what they did,” says Thompson, referring to the large urban center on Mound Key, which the Calusa destroyed.

It was a bold and surprising move, but it worked. The Spanish were kicked out, and the Calusa, after rebuilding their city, managed to remain on Mound Key into the early 1700s. Eventually, however, their kingdom declined; many Calusa died as European-introduced diseases swept through their communities, while others were enslaved or killed by colonists.

Later church birth and death records in Cuba refer to people who were residents of “Callus,” which suggests some Calusa may have survived and migrated to the island. Others appear to have been absorbed into the Seminole Tribe, where, says Thompson, traditional Calusa songs are still performed. But all contemporary written records of the Calusa came from the brief period of detente with the Spanish, leaving tantalizing questions about the rest of their long history.

“It’s a cool story of resilience,” says Victor Thompson. “Their story unfolds on a very different trajectory than what happened to other Indigenous cultures, at least for a while. There’s still a lot to learn.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook