The Small Script-Copying Service That Powered NYC Entertainment for Decades

Among many other jobs, Studio Duplicating staff did frenzied, last-minute typing for Saturday Night Live.

In 1957, playwright Tennessee Williams received an offer he couldn’t refuse. Recommend Studio Duplicating Service to your friends, said its founder, Jean Shepard, and we’ll print your scripts for free.

So begins the story of a copy shop that opened on 9th Street in New York’s East Village that year, and for the next four decades printed the lion’s share of scripts for the city’s entertainers in film, television, and the theater.

The story of the shop and the paper it churned out is the secret history of the printed archive of the New York entertainment industry for almost half of the 20th century, sitting squarely at the intersection of the history of drama, printing, and labor. It’s also the story of a woman entrepreneur whose working life was designed to maintain her life as a creative person, and how the business helped her employees do the same along the way.

Everybody from Edward Albee to Spike Lee went to Studio Duplicating. From 1975 to 1997, NBC’s Saturday Night Live was one of Shepard’s biggest and most demanding customers. A first draft of an episode’s script came into the shop on Friday evening, and Studio staff worked through the night to get it printed by Saturday morning. A round of revisions came back Saturday afternoon, and new pages were delivered to NBC Studios in time for evening rehearsals after a frenzied round of proofing, typing, and printing. ABC was another major client, hiring Studio Duplicating for soap operas like All My Children and Dark Shadows. Typists got hooked on the stories and fought to type the soaps to get a sneak-peek at new episodes before they aired.

These three shows were a few of many loyal clients that helped the business grow. Scripts for movies shot in New York were constantly coming in, and a lot of play- and screenwriters were repeat customers. Woody Allen was a major client, and Jean’s son Grey Shepard, who I interviewed for this article, recalls reading his newest scripts over the dinner table with Jean.

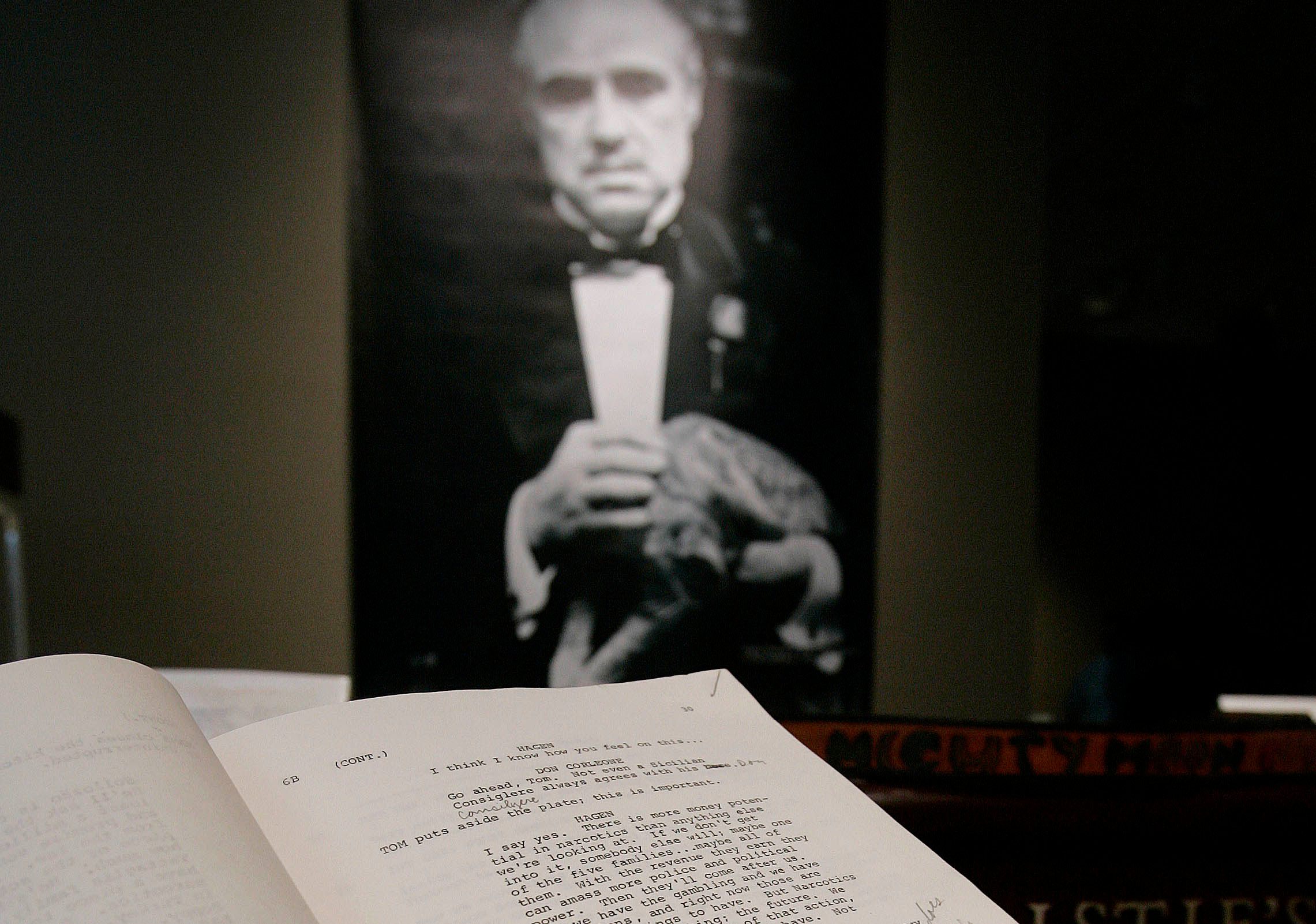

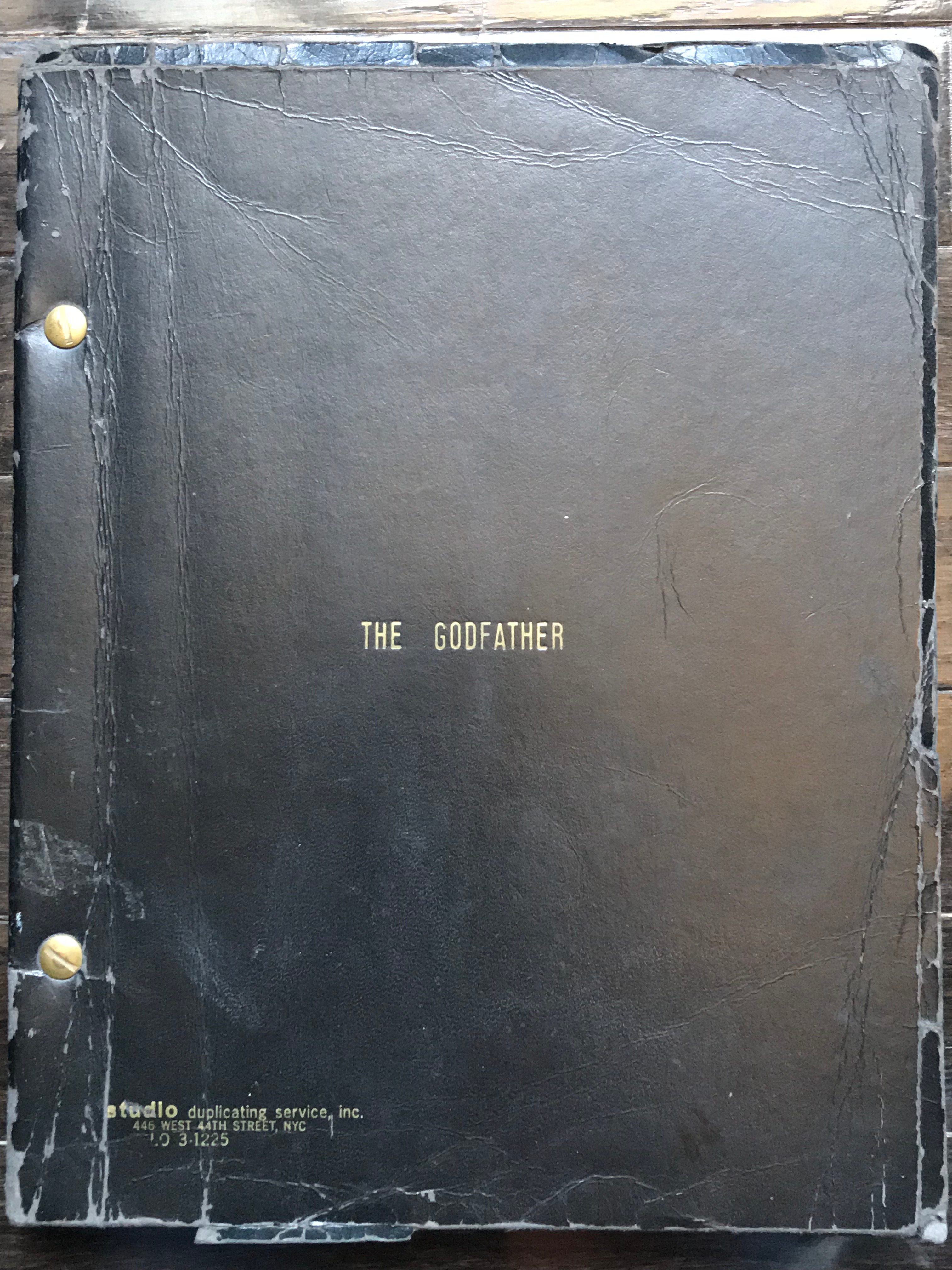

Allen often edited his work in person at a desk reserved for writers in the shop. Elaine May, Terry Southern, William Goldman, and Spike Lee were just a few of the screenwriters whose scripts were printed there. One of Grey’s summers off from school was spent mimeographing, collating, and binding shooting scripts for Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather.

Major work for television signaled the height of the Studio Duplicating Service, which was by then an all-night operation that employed around 30 people in a brownstone on 44th Street between 9th and 10th Avenues. Studio Duplicating took up the ground floor, and the Shepards’ home—which featured an indoor badminton court and art studio—was on the upper floors. The shop’s beginnings, however, were humbler. Shepard and her founding business partner, Patricia Scott, rented a tiny office in the back of a dry cleaner’s shop on East 9th.

In those early years, most of the work they printed was for theatrical productions on and off Broadway. Among the nearly 600 scripts printed by Studio Duplicating in the New York Public Library are scripts by Tennessee Williams, Aldous Huxley, Irving Berlin, Eugene O’Neill, Arthur Miller, Lillian Hellman, and Truman Capote. Scott sold her share in the business in 1961, and that year Studio Duplicating relocated to larger quarters on West 43rd Street. Six years later, Shepard purchased the 44th Street brownstone. Grey remembers how rough the block was in those days. His mother, however, loved dogs and they always kept two German shepherds that went with them almost everywhere. Nobody messed with the Shepards because nobody wanted to mess with their dogs.

Grey also recalls that most of Studio Duplicating’s employees were men—he remembers only five women who worked there—and that they were working actors. There were a handful of writers, too, and anyone who wasn’t working yet was trying to make it. One employee to go onto a successful acting career was Marcia Wallace (1942-2013), who played receptionist Carol Kester on The Bob Newhart Show and voiced Edna Krabappel on The Simpsons. Joel Parsons, an actor traceable to productions of Shakespeare’s As You Like It and Henry IV, worked as a mimeographer at Studio when the business opened, and stayed on for 30 years.

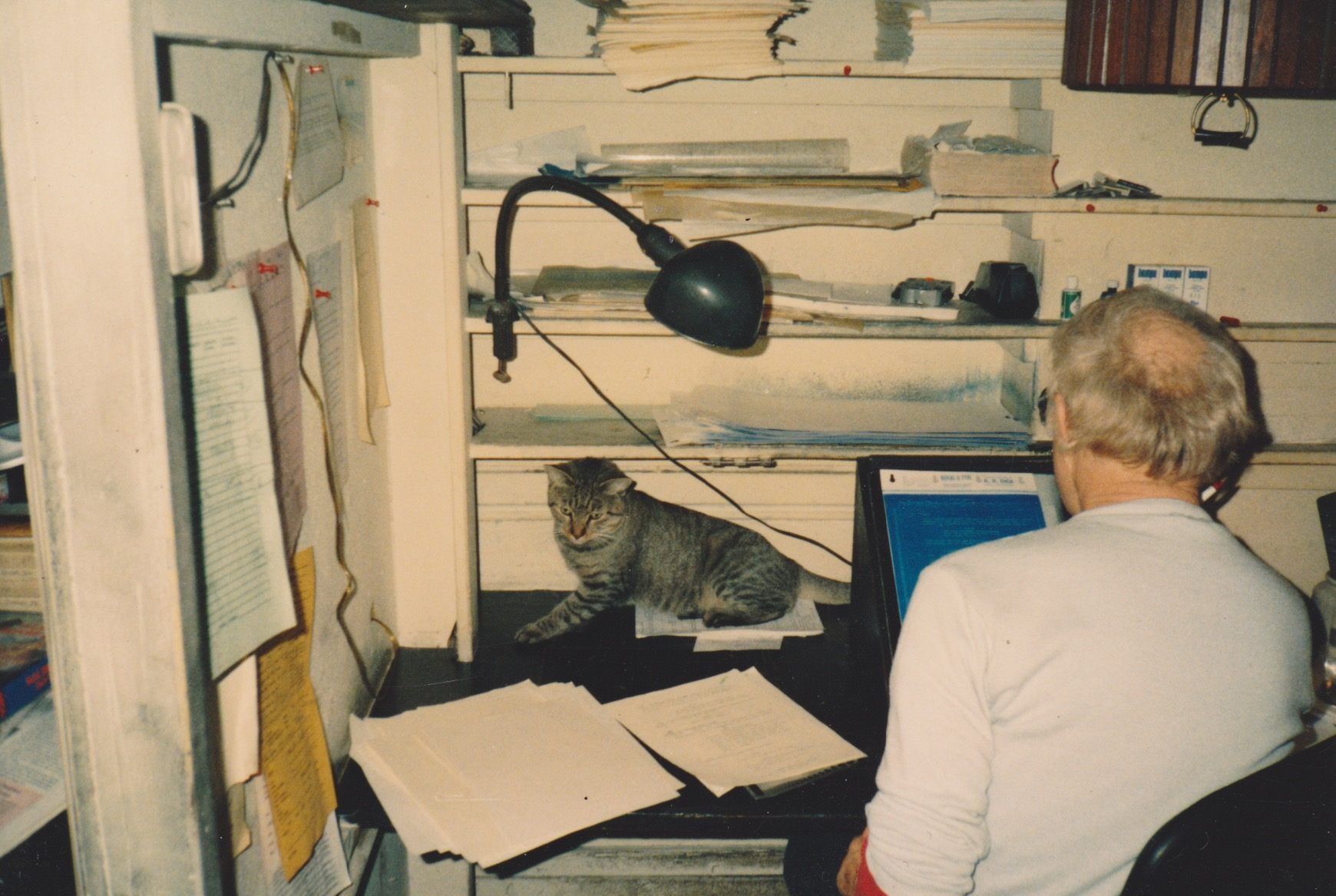

Working at Studio Duplicating was a great gig for actors because their boss understood the ebb and flow of the profession. Shepard readily gave time off for performances and auditions, and if someone got a part in a touring company, he could hop on the bus for three months and his job would be waiting when he returned. Shepard gave herself the same flexibility. She hated mornings and refused to take calls before noon, and also spent part of each day writing, painting, or at her pottery wheel. She devoted time in the afternoon and late at night to the business, keeping up with orders, billing, and bookkeeping in the wee hours.

Shepard was well connected to the theater world partly because she trained as a lighting designer at Northwestern University in Illinois, where she met her actor-husband, Richard Shepard. (They divorced in the early sixties but remained close friends.) Co-founder Patricia Scott was a singer and actress, and her actor-husband was George C. Scott, a.k.a. General Patton and General Buck Turgidson. Their social and professional network was the New York theater world, and they ran a business that never advertised to attract new clients or staff. Hiring actors to work at Studio Duplicating made sense because it was the first print shop in New York to specialize exclusively in scripts. Having a great American playwright vouch for your services is a pretty good way to get started in business, but Studio Duplicating lasted because they got scripts right, at least in part because everybody who worked there knew from experience what right looked like.

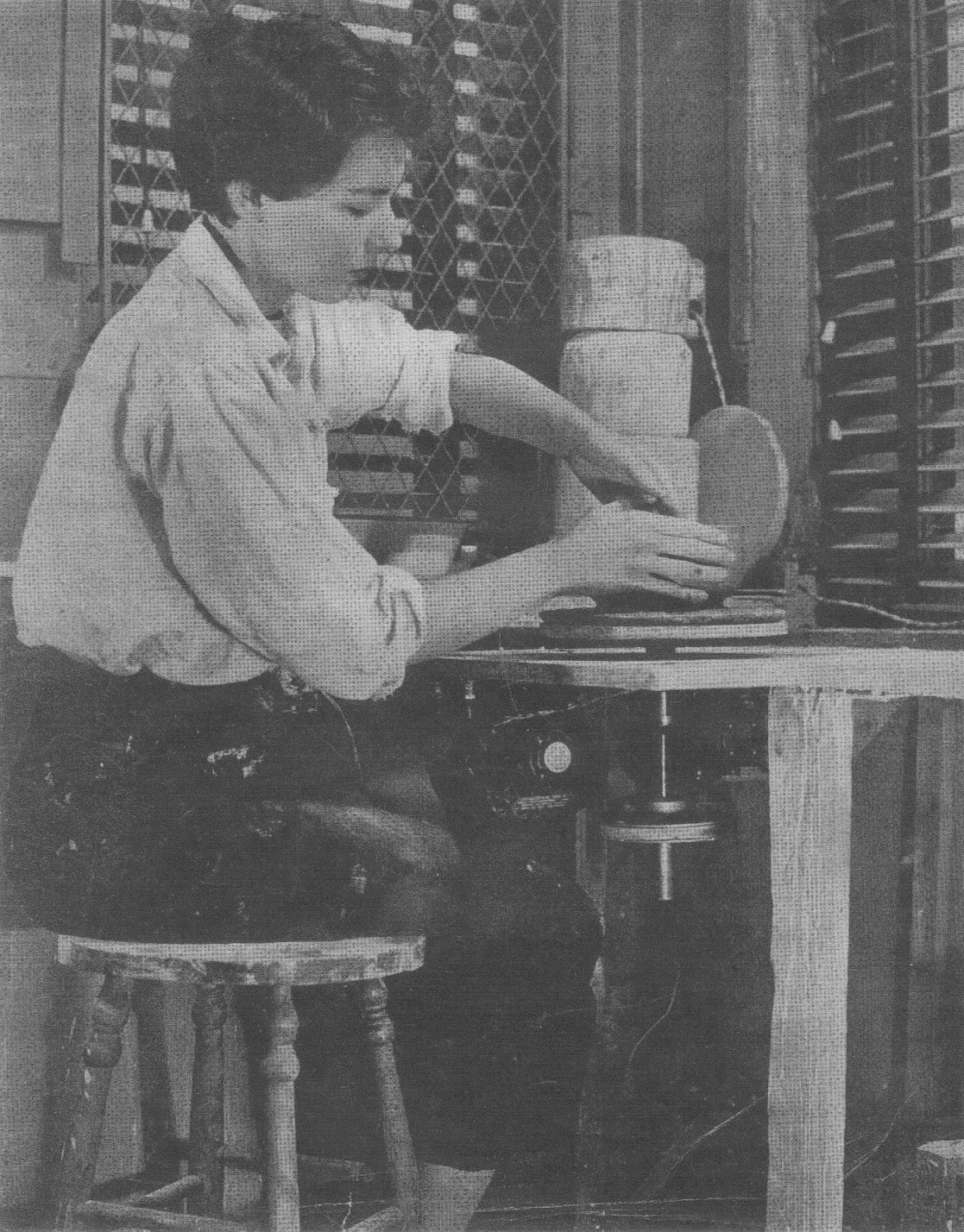

Studio Duplicating’s employees were proofreaders, typists, mimeographers, or binders, and scripts passed through their hands in that order. Proofreaders never interfered with the text, but read things through to regularize spelling and punctuation and make sure the script was complete. Some writers’ manuscripts always went straight to the only proofreader who could read their uniquely indecipherable handwriting. Corrected manuscripts next went to typists, who typed up one mimeograph stencil for each page of text.

The mimeographer would then affix the stencil to the cylindrical drum of the motorized machine, and power it on to turn the drum and stencil across an inked pad. Typed holes in the waxy surface coating on the blue mimeostencil absorbed the ink, and transferred it to blank sheets of paper. Scripts were printed and collated sheet-by-sheet, then hole-punched and bound in colored vinyl stamped with the title and the Studio Duplicating Service logo. In the early 1990s the shop bought a Xerox machine and word processor—mimeograph supplies were difficult to obtain, and by then the business served only a handful longtime, major clients—but their archive of mimeostencils stayed in storage in the shop basement until the doors closed for good in 1997.

Mimeo was a great technology for a small printing business. The machines required a relatively small investment, were easy to maintain and operate, and supplies were inexpensive. It worked really well for scripts because the typed stencils were easy to file and store. This meant that a writer, agent, producer, or director could order new copies of a script and expect a quick turnaround—no retyping required. It was also easy to keep scripts up to date with the latest revisions, and print either a full revised script or just revised pages. This was crucial, because in both the pre-production and production phases, screenplays and stageplays often went through multiple rounds of revisions. Many scripts also spent months or even years in development. An order might come in for just a few copies, and work on revisions and a larger print run would follow if and when production started. The stencils stayed in the Studio Duplicating archive for years, and even after they stopped printing new jobs with the mimeo machine they could still run off copies from a mimeostencil long after it was first created.

In the author bio in Nobody Home, the novel she published in 1977, Shepard alluded to her work with Studio Duplicating Service last, saying “Jennifer Lloyd Paul is the pseudonym of a writer, artist, and businesswoman.” Before publishing Nobody Home, which was warmly reviewed by the New York Times, her clay work stocked New York City’s first Pottery Barn when it opened in 1963. A play based on her novel called A Firehouse Bride opened Off Broadway in 1985.

Today we remember Shepard first as the brains behind the small yet significant printing operation that manufactured the printed matter essential to New York’s entertainment industry, much of which still survives in public and private collections across the country. But Shepard’s life and her business were supportive of one of the creative worlds she loved in more ways than one. Shepard’s understanding of her own need to make a living without sacrificing her life as a creative person gave her the perspective to make the same thing possible for the people who worked for her. The plays, TV shows, and movies that Studio Duplicating staff wrote or acted in may have never brought them fame and fortune, but they considered themselves actors first and their work in the shop made it possible for them to do what they loved when they could and still make rent.

Movies, television, and the theater need scripts and actors. Studio Duplicating gave them both.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook