The Center of the Earth Has an Imaginary Island and One Floating Soul

Fact and fiction blend together at zero latitude and zero longitude.

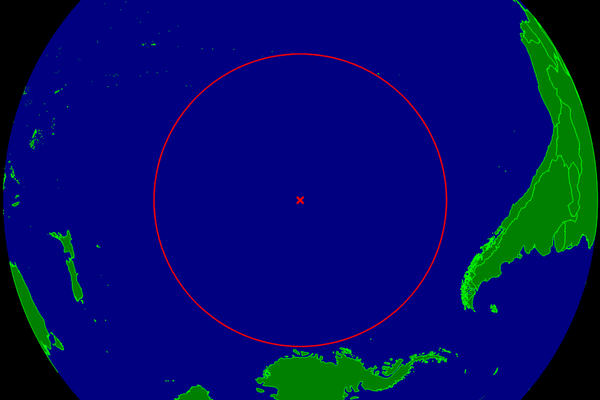

You’ve got a list of geocoded data points, but due to error or omission, one of them has nothing set as its location. It may still show up on a map. If so, look for its pin to drop on a very specific place in the international waters off the Gulf of Guinea: Null Island.

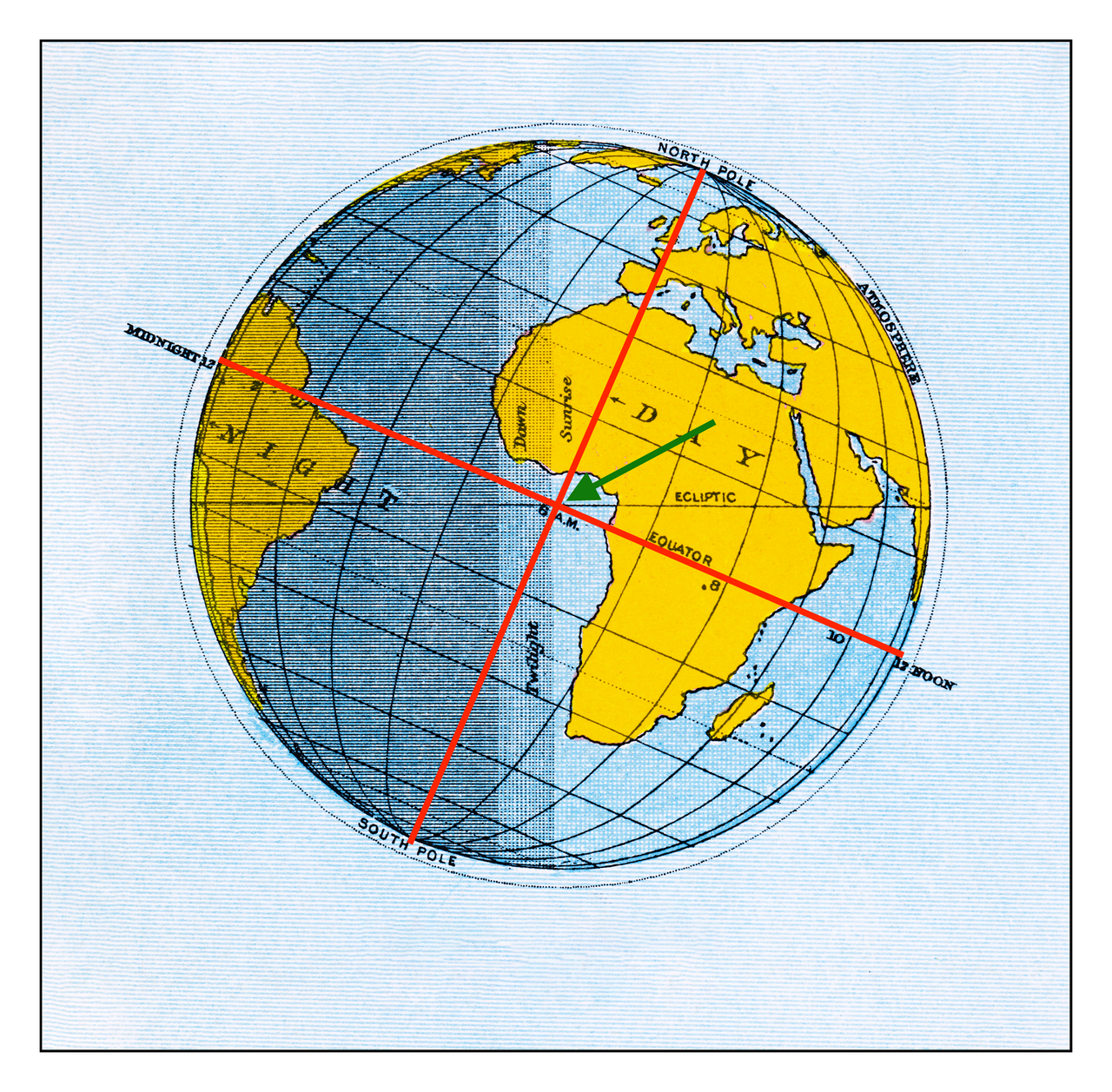

Think of the Gulf of Guinea, part of the South Atlantic Ocean, as Africa’s armpit. It’s the body of water just off the coast of where West Africa bends south to become Central Africa. The Gulf is right in the middle of your standard world map, and that’s no coincidence. It is the meeting point of the two baselines of geodetic measurement, the prime meridian and the equator. Or, expressed in longitude and latitude: 0°N, 0°E.

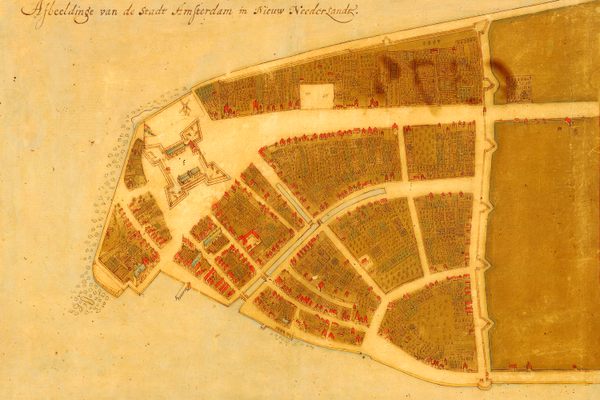

You guessed it: this is Null Island—the perfect anchorage for non-geolocated data. But don’t go rent a boat on the coast of Ghana or the island of São Tomé, two of the nearest bits of dry land. After crossing about 400 miles (650 km) of open water, you will find more of the same upon arrival. Because, true to its appellation, Null Island is not an island.

Null Island is merely the colloquial name for the intersection of these two prime orthodromes. In mathematics, and by extension also in geodesy, an orthodrome (or great circle) is the longest possible line drawn around a sphere, thus dividing it into two perfectly equal halves, or hemispheres.

The Equator, equidistant from the poles, gives us the northern and southern hemispheres. The Greenwich meridian, which divides the world in eastern and western hemispheres, is a more arbitrary line. Its status as the world’s prime meridian was established only in 1884, at the International Meridian Conference in Washington D.C. The French abstained from the final vote; they had campaigned for the Paris meridian.

So 1884 is year zero for our point at zero north, zero east. Because of its remoteness, the location remained culturally insignificant until 2011, when it showed up in the public domain map dataset of Natural Earth as “Null Island.”

That naming started off a remarkable process: it turned something non-existent into something imaginary, which is not quite the same. Suddenly, maps were drawn of Null Island, flags designed, fake backstories conjured up.

Squint, and you can almost see the island now. A small, tropical purgatory, far away from anywhere that matters, home to uncountable damaged and incomplete data points, stranded until they are fixed or erased. The weather is always humid, and there’s never a ship on the horizon.

An entire island has been given over to the world’s untethered data. The idea almost makes you wish that Null Island was real. But wait, there actually is something other than nothing at Null Island.

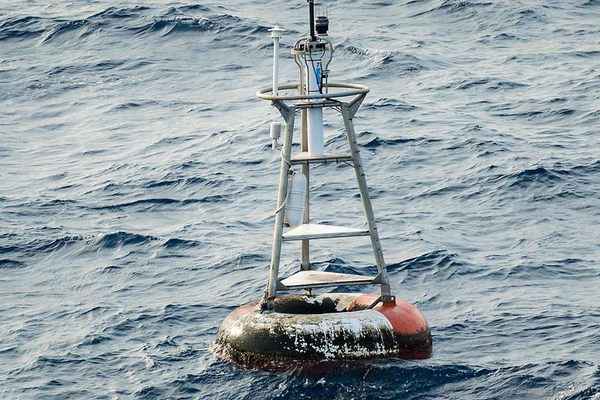

In 1997, the U.S., France, and Brazil installed a set of 17 weather and sea observation buoys in the South Atlantic, called the PIRATA system. One of these is moored to the seabed (about 16,000 ft or 5 km deep) at exactly 0°N, 0°E. This is station 13010—also known as “Soul Buoy”—measuring air and water temperature, wind speed and direction, and other variables at zero zero point.

All of the 17 buoys, each named after a different music genre, are inspected annually, as the buoys attract fish, hence also fishing boats, whose visits can cause damage to the equipment or the buoy itself.

It would appear that, as non-existent places go, Null Island is more solid than most.

This article originally appeared on Big Think, home of the brightest minds and biggest ideas of all time. Sign up for Big Think’s newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook