The Thorny Tale of America’s Favorite Botanist and His Spineless Cacti

Luther Burbank dreamed of deserts filled with cow food.

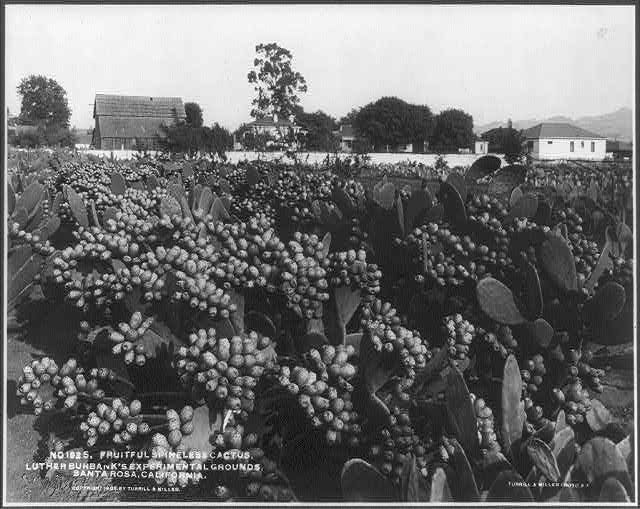

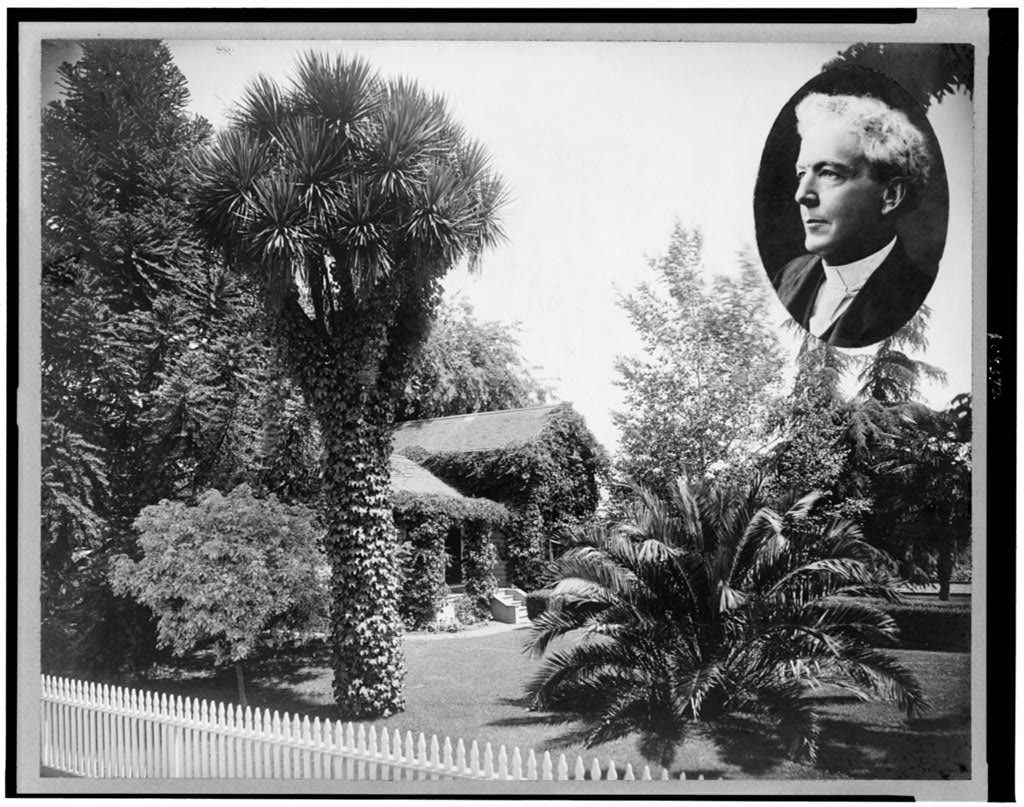

In the early-20th century, Luther Burbank was a botanical superstar. Tourists, foreign envoys, and celebrities flocked to his home in Santa Rosa, California, clamoring to see the marvels the “plant wizard” developed in his garden. For years, they watched in awe as Burbank rubbed his face on large, fleshy cacti pads that were seemingly smooth as silk. It was a demonstration of one of his proudest achievements: breeding cacti to have no spines.

Burbank seemed to possess “the uncanny ability to bend nature to his will,” writes Jane S. Smith, author of The Garden of Invention: Luther Burbank and the Business of Breeding Plants. For the man who had created a stoneless plum and bred the progenitor of the world’s most popular potato, making a spineless cactus must have seemed a matter of course. The Opuntia prickly-pear, which bears fruit and has edible pads, had long been a Central American food source. Burbank, though, dreamed of using it to produce cattle feed in the world’s deserts. If cows could munch on his thorn-free cacti, it would free up rich agricultural lands for human use.

But due to his massive fame, his unfortunate tendency towards showmanship, and wild speculation, Burbank ended up selling not-so-spineless cacti, tarring his reputation until the end of his days.

Rachel Spaeth, curator at the Luther Burbank Home & Gardens, calls it “the cactus folly.” Burbank, she notes, had a special affinity for cacti even as a child in Massachusetts. “When he was a kid, maybe five or six years old, he had a pet cactus,” Spaeth says. It was a relatively spineless, night-blooming cereus.

A hard worker and keen observer, Burbank experimented as a young man with cross-breeding plants, developing the slapdash methods that would later drive other botanists wild as they tried to unravel his work. The fruits of his labor literally bore fruit, though. At age 26, he sold the rights to the Burbank potato for $150 dollars. (A future mutation of this potato, the Russet Burbank, is now the world’s most-grown spud.) With the money, he moved to the perfect plant-growing region of Santa Rosa. His love of cacti followed.

There, Burbank bred wonders, from a white raspberry to a red California poppy. His fame surged, largely due to the many admirers, journalists, seed companies, and California boosters who upheld him as a botanical star. But he struggled to profit from his work. At the time, which was something of a golden age for American horticulture, the unscrupulous stole and sold seeds and cuttings with impunity. Creators such as Burbank never saw much of the money. He considered this bitterly unfair, and after his death, Thomas Edison testified in Congress to encourage a bill that would allow for the patenting of plants.

Burbank’s challenge, then, was to simultaneously release new plant varieties and promote them. Breeding a spineless cactus for the enormous cattle industry must have seemed like the perfect solution. In the late-19th century, ranchers in arid areas sometimes fed cacti to their cattle, especially during droughts. When cows ate spiky cacti, they typically ended up with painful wounds on their gums and mouths. According to Smith, in Luther Burbank’s Spineless Cactus: Boom Times in the California Desert, ranchers had to burn off spikes with gasoline torches.

So Burbank and his supporters imported cacti from around the world for experiments. Crossbreeding cacti is fairly straightforward, Spaeth says, often simply requiring transfer of pollen from one flower to another. But Burbank devoted more effort to breeding cacti than to any other crop, and his experiments spanned 20 years. By working mainly with the Opuntia ficus indica and the Opuntia robusta, which have reduced spines to begin with, Burbank released dozens of new prickly-pears varieties.

Excitement simmered for years, even in places nowhere near the desert. One 1904 New York Tribune article rhapsodized about the food possibilities for both humans and cattle, stating that Burbank’s cacti were “capable of growing on the [driest] desert” and “may mean to some districts more than the introduction of the potato meant to Europe.” The next year, the Los Angeles Times dreamily wrote that “this wonderful man” was paving the way for “big cactus farms.” The cactus, Burbank imagined, would be harvested and then fed to cattle, to keep them from chewing the plants to the ground. But others envisioned cattle grazing on cactus in formerly wasted deserts, eating straight from the source.

In 1907, writes Smith, Burbank released a catalog announcing his “improved” spineless Opuntias to a public primed for wonder. But there was a problem. Burbank’s spineless Opuntias didn’t really like the desert. To grow at the promised rate, the cacti needed water, which meant irrigation. In too-harsh conditions, they could even regrow their spikes as a defense mechanism. Worst of all, both cows and wild animals devoured them eagerly, not minding any of the tiny glochid prickles still present.

That last part might not seem like a problem, but the cacti simply could not grow quickly enough. (Ironically, in one pamphlet advertising his spineless cacti, Burbank lyrically mused that the Opuntia, with its “rich stores of nutriment and water,” must have developed fearsome spikes to protect itself from hungry critters.) Putting up fences in the desert and providing irrigation wasn’t the plant-it-and-forget-it solution to cattle feed that American farmers wanted, Spaeth says. Burbank even noted several of these limitations himself, yet both he and the press continued to market the spineless Opuntias as something of a miracle. Orders came in from around the world, and developers sold arid land with the promise that it could be planted with green gold.

There was some pushback. Government publications pointedly noted that spineless cacti existed before Burbank, which spurred him in 1910 to cable the New York Times and protest that he had never claimed to have invented it. Yet he also planted a relatively spineless Opuntia ficus indica amidst a thicket of extremely spiny cacti at his home, a visual suggestion for visitors that one botanist called “misleading to the uncritical.” For his face-rubbing demonstrations, he used a pad that had been worn to smoothness by repeated use. Sometimes, Spaeth suspects, he had to shave glochids off his face.

But Burbank’s most foolish decision was whom he entrusted with his reputation. He never had a head for business. Often, Burbank left marketing and distribution up to others, and “that came back to bite him,” says Spaeth. In 1913, Smith writes, some enterprising businessmen “who knew nothing about plants” paid Burbank $30,000 and an annual fee for the right to sell his creations under his name.

Disaster ensued. Any order that came in, the Luther Burbank Company filled, even when there was no supply. Using blow torches, they seared the spines off normal Opuntias and shipped them. But even this deceit couldn’t save the company. It went out of business in 1916, and Burbank’s reputation, writes Smith, “among growers and [in] academic circles, never fully recovered.” When he died in 1926, Spaeth says, his cacti plants were “an incredible mess for his widow to clean up.” In the end, Elizabeth Burbank saved and replanted only seven cultivars.

“Time and again,” Burbank wrote in 1914, “I have declared from the bottom of my heart that I wished I had never touched the cactus to attempt to remove its spines.” This sentiment was inspired by Burbank’s frustration with tiny, painful glochids. Yet it also seems prescient of his looming stumble.

These days, many of Burbank’s cacti are referred to as “mostly” spineless. Spaeth, who prunes the two-story-tall Burbank cacti still growing at the Home and Gardens, notes dryly that they’re definitely not completely spineless. But one kind, Florida White, has peachy, nearly spineless fruits, while another, Pyramid, makes for excellent fodder. Despite a brutal freeze that nearly killed them off in 1996, they’ve proven remarkably resilient. It’s probably because there are no cows around, who would likely devour them, glochids and all.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook