The World’s Most Mysterious Medieval Manuscript May No Longer Be a Mystery

But we’re not reading the Voynich manuscript quite yet.

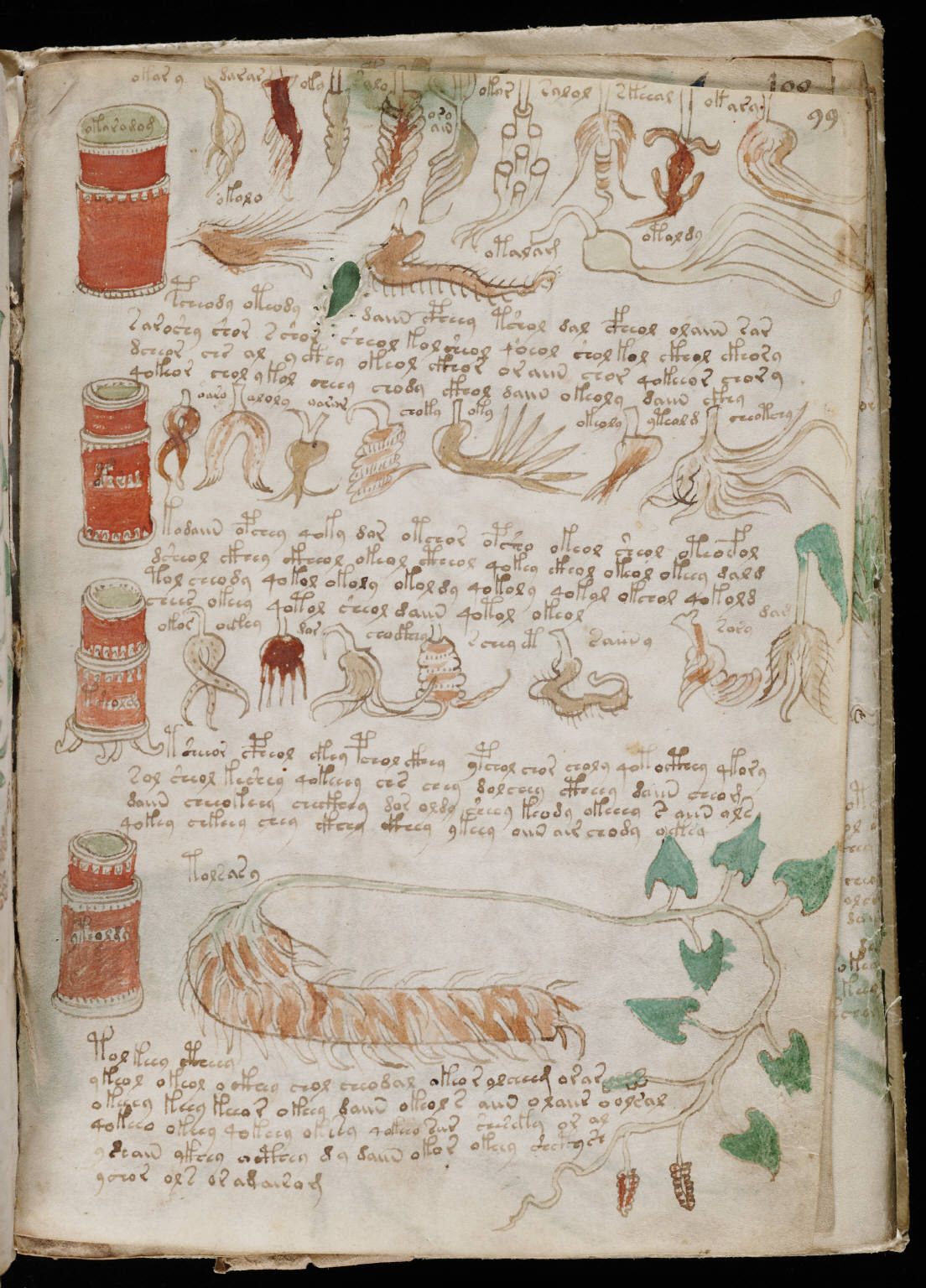

The Voynich manuscript, a 15th-century document full of undeciphered writing and a variety of cryptic illustrations, has invited its fair share of conspiracies. Named for 19th-century Polish bookseller Wilfrid Voynich, it has been suggested to be a Victorian forgery, the guide to the philosopher’s stone (real or scam versions), and even the work of a lonely alien adrift on Earth.

But Nicholas Gibbs, an expert on medieval medical manuscripts, says the answer may be far more prosaic than any of that. In an article in the British Times Literary Supplement, Gibbs explains that the manuscript seems to be made up of Latin ligatures—a kind of shorthand. “Ligatures were developed as scriptorial short-cuts,” he writes. “They are composed of selected letters of a word, which together represent the whole word, not unlike like a monogram.”

The ampersand (&) is a common example. Its design incorporates the letters “e” and “t,” which spell the Latin “et,” meaning “and.” Each symbol in the text represents a whole word rather than a single letter, Gibbs says. Challengingly, however, any possible index to these abbreviations is missing, making the script “resistant to interpretation,” at least for now.

The Voynich manuscript appears to be some kind of medical encyclopedia, with detailed information on which herbs in what quantities can cure gynecological conditions. Its information, Gibbs writes, seems to be drawn from standard treatises of the medieval period, to form “an instruction manual for the health and well-being of the more well-to-do women in society, which was quite possibly tailored to a single individual.” So much for the conspiracy theories, which may date back to its eponymous owner, who claimed it had previously belonged to 13th-century friar and philosopher Roger Bacon. Bacon had a history of using a cipher in his work to hide it from the watchful eyes of the Church. This all led to the belief that the manuscript had deliberately been written in a secret code, and was hiding something important.

This, in turn, made it very popular with cryptographers. During World War II, prominent codebreakers spent time trying to unlock the work, but failed to find any meaning. Some people concluded that it is just “gibberish.” As recently as 2013, researchers believed that it was mostly likely a hoax. “There have been numerous encrypted texts since the Middle Ages and 99.9 percent have been cracked,” Klaus Schmeh, a cryptographer, told the BBC. “If you have a whole book, as here, it should be ‘quite easy’ as there is so much material for analysts to work with. That it has never been decrypted is a strong argument for the hoax theory.”

But Gibbs told The Times of London that it is extraordinary that such an easy solution had not previously been suggested. “Human beings are not naturally complicated,” he said. “They look for short cuts all over the place. If you are writing something, you don’t want to spend your time [writing the same thing repeatedly], so you have indexes. The manuscript needs an index to work.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook