The Most Amazing, Smelly, Deadly Fungi in North America

Handing out superlatives to some overlooked species.

Some fungi glow an eerie green. Some just reek to high heaven. Some are deadly, others save lives. (Consider, for instance, Penicillium chrysogenum, the golden fuzz that lab assistant Mary Hunt, nicknamed “Moldy Mary,” saw growing on a canteloupe in Peoria, Illinois, in 1943—and which could produce penicillin in far greater quantities than the species famously grown in Alexander Fleming’s lab.)

Despite their variety and range of uses, fungi get neglected, says Andrew Miller. A mycologist and director of the herbarium and fungarium at the Illinois Natural History Survey, Miller spends his whole life around spores, rhizomorphs, and sporocarps, so maybe it’s no surprise that he thinks they don’t get the love they deserve.

This is partly a numbers problem. “For every plant species, [it is said that] there are 30 botanists,” Miller says. “I would estimate that for every single mycologist, there are probably 100,000 species. The ratios are completely off the chart.” As a result, researchers haven’t always known exactly what lives where. Until mycologists recently began digitizing their collections, Miller says—long after botanists and other specialists had done so—specimens were gathering dust in cabinets, with handwritten or typed labels that were largely hidden from the rest of the world. It’s hard to spot an new species, emerging pathogen, or invasive pest if you don’t know what is there to begin with.

To help researchers get a handle on which fungi live where, Miller recently helped spearhead an effort to catalog them in a single, sprawling checklist. With collaborator Scott Bates, from Purdue University Northwest, and assistance from the Macrofungi and Microfungi Collections Consortia, Miller wrangled information about 44,488 species found across North America. The team published this who’s who in the journal Mycologia.

The 127-page paper is a behemoth, and Miller says it’s just the beginning. Earth is home to probably millions of fungal species, he says, and researchers are still in the kiddie pool. The list “is not the be-all, end-all, but it’s a good start,” he adds.

It’s also a good chance to get acquainted with all the kinds of fungus among us. The most common are Lycoperdon perlatum (or common puffball) and Schizophyllum commune (the split gill mushroom). Atlas Obscura asked Miller to introduce some of the other stand-out, superlative specimens.

Most stinky

When asked about the continent’s smelliest fungi, Miller offered an instant answer: It’s Mutinus caninus, known as the “dog stinkhorn” on account of its resemblance to a canine penis. “It’s nature, and I didn’t name it or invent it,” Miller says. “It just is.”

The mushroom lives primarily underground until it erupts, often from piles of wood chips or mulch, to expose its foul-smelling fruiting body. When it does, Miller says, “You might smell it before you find it.” The stink is, shall we say, lewd. “To be completely honest, it has a spermatic odor.”

It gets worse. The spores are contained in a slimy mass on the mushroom’s tip, or gleba. Flies land there and pick them up, dispersing them as they buzz along. The odor vanishes once the spores are spread.

Most sprawling

The so-called “Humongous Fungus” lives up to its name. Stretching across 2,200 acres in Oregon, an interlocked network of Armillaria solidipes (also known as Armillaria ostoyae) is possibly the largest living thing on Earth. It’s been growing in Oregon’s Malheur National Forest for at least 2,400 years, and with all of its fine underground filaments, it weighs considerably more than a blue whale (or three). “It’s by far the winner for oldest, largest, and heaviest,” Miller says. Even its smaller, younger cousin, a specimen in Crystal Falls, Michigan, is a whopper that covers 90 acres.

In terms of mass and footprint, Calvatia gigantea is not close to those leviathans, but it has the outward appearance of something particularly oversized. The giant puffballs, which are found in temperate forests and meadows, can grow to the size of a human head and hold a trillion spores, Miller says. If every puffball’s spores germinated and grew, he estimates, combined they could weigh more than the Earth itself.

Most minute

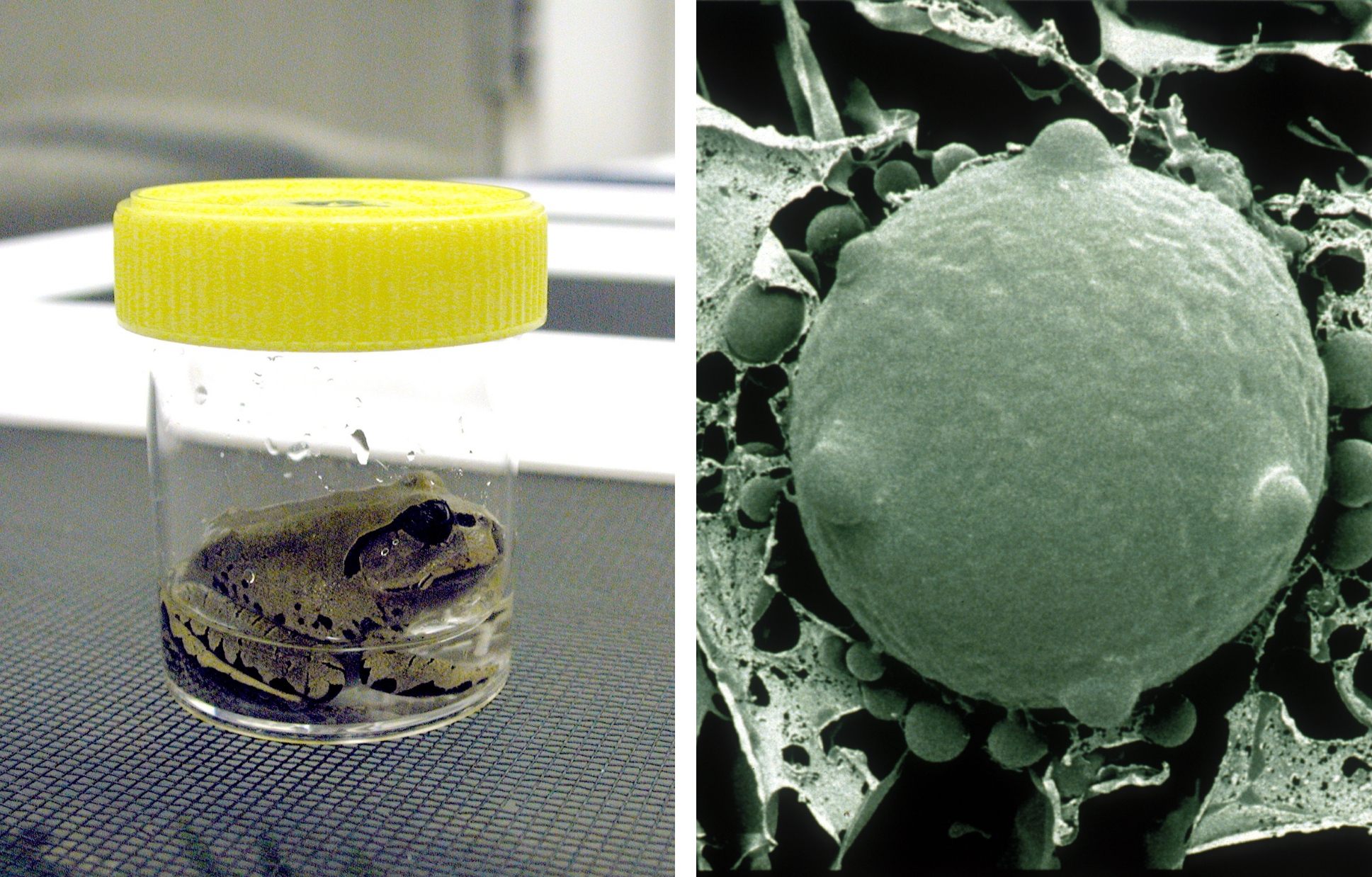

It’s tricky to pinpoint the very smallest of the small, since there are various species of unicellular fungi, but a strong contender is the members of the group Chytridiomycota. These aquatic fungi, also known as chytrids, are “the poster child for really small, tiny fungi,” Miller says. “I work on microfungi, but these are too small even for me.”

One chytrid, Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, is known for having decimated amphibian populations in Central America and Australia beginning in the late 1980s. (It’s also been present in North America for decades.) The species’ zoospores, which measure around 3 to 5 micrometers in size, use a much longer flagellum to wiggle into amphibians’ skin. Once lodged there, they can induce skin diseases, ulcers, and even cardiac arrest.

Most lethal

It’s always good practice to avoid nibbling on mushrooms that you can’t identify with absolute confidence. But whatever you do, don’t eat Amanita phalloides. It’s commonly called a “death cap,” and the name is well-earned.

These commonly sprout up and down the West Coast of the United States, often from live oaks and other hardwood trees. Eating just one could do a number on your liver and kidneys and ultimately lead to death, Miller says. “Other mushrooms can make you sick—vomiting and diarrhea—but this one kills you,” he adds. “It’s not good stuff.” The death cap contains alpha-Amanitin, one of the toxins most associated with deaths from mushroom poisoning, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The toxins aren’t tamed when the mushroom is cooked, dehydrated, or frozen, and three of the 14 people sickened by foraged death caps in Northern California in 2016 needed liver transplants. Stay away, Miller cautions. “It just takes a few bites.”

Most deceptive

This one is open to interpretation, but a number of fungi species have surprising lookalikes. The pink, fleshy Rhodotus palmatus looks a bit like a brain, or a wrinkled peach long past its prime. Fittingly, it’s also known as the “rosy veincap.” Species in the genus Hercium, on the other hand, recall the depths of the sea. Found in shaded deciduous or alpine forests, the branching spines look like terrestrial coral or anemones.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook