Was This Letter Written by Sherlock Holmes?

If you are “Playing the Game,” the answer is elementary.

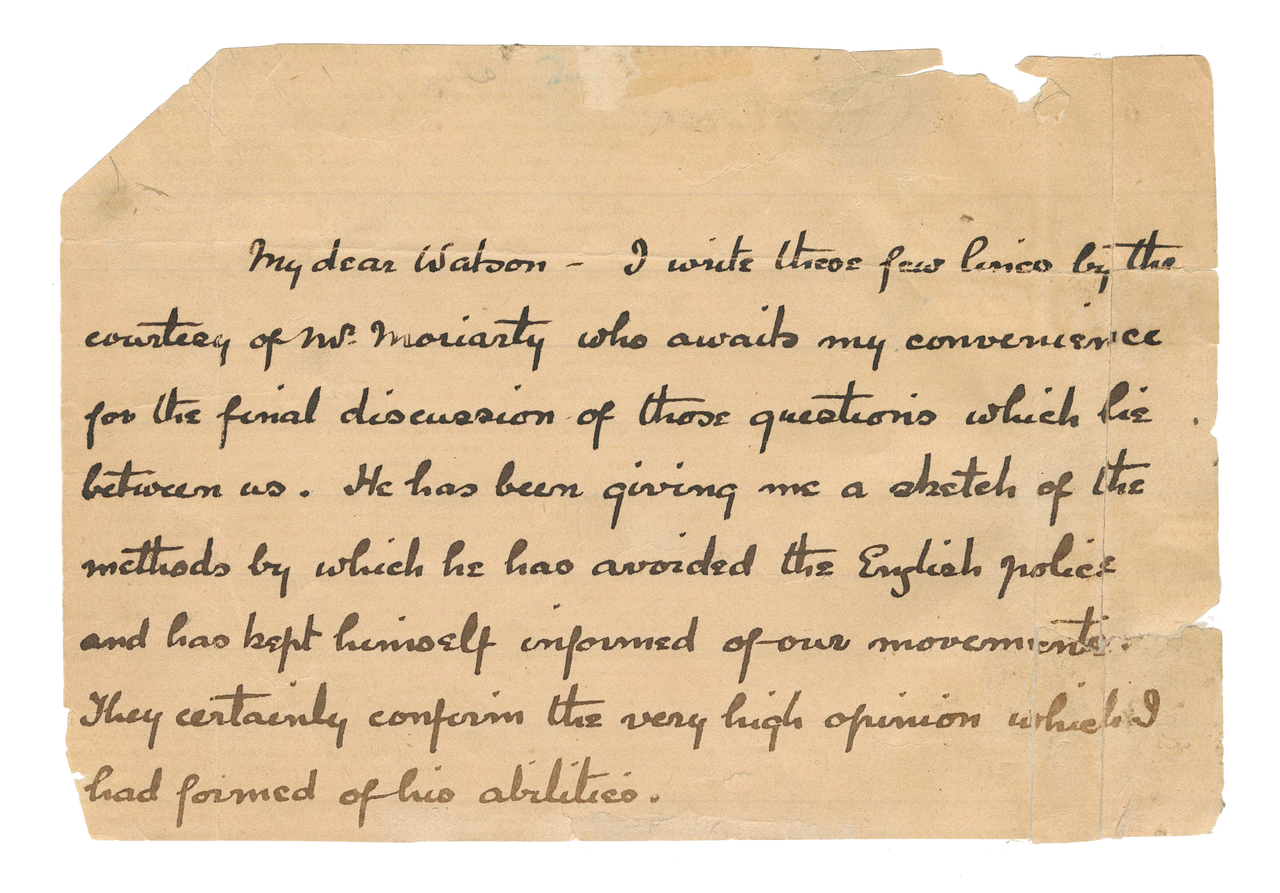

In the archives of Indiana University’s Lilly Library there is a small scrap of paper, no bigger than an index card. The century-old fragment is yellowed and battered, but the handwriting remains firm and clear. “My dear Watson,” it reads, “I write these few lines by the courtesy of Mr. Moriarty who awaits my convenience for the final discussion of those questions which lie between us.” Though the letter is undated and unsigned, one doesn’t need to be Sherlock Holmes to deduce the author and his predicament: It is clearly meant to be the famous detective himself, in the last moments before his ultimate confrontation with his nemesis.

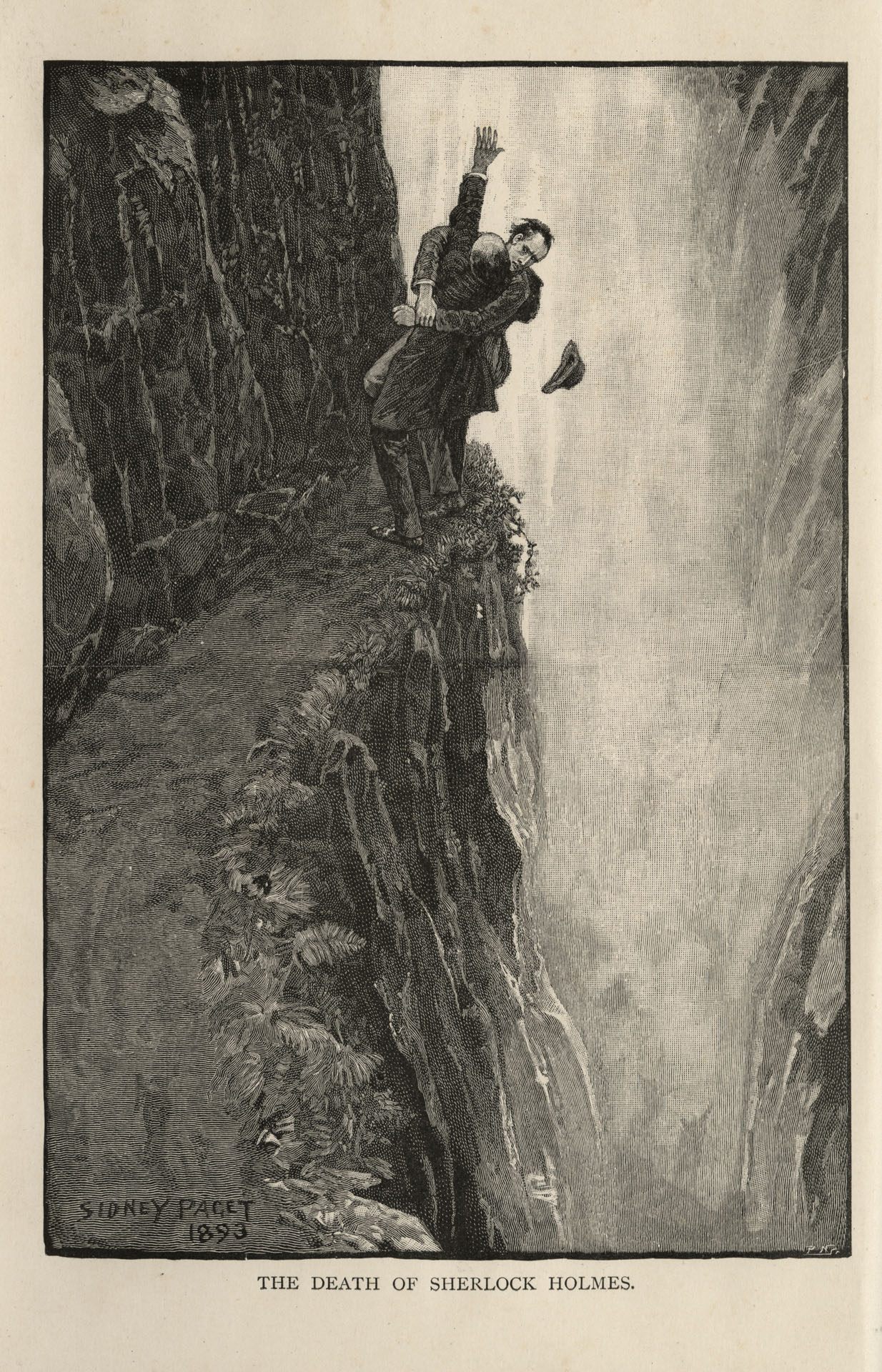

“It looks like a surviving fragment of an actual letter, right?” says Erika Dowell, Lilly Library’s curator of modern books and manuscripts, as she examines the paper. In an 1893 short story called “The Final Problem,” John Watson quotes from the letter and explains how he found it on a narrow mountain ledge in the Alps outside Meiringen, Switzerland. It was there, he concluded, that Holmes tumbled to his death in the rushing waters of Reichenbach Falls.

Dowell knows, of course, that Sherlock Holmes is a fictional character created in 1887 by Arthur Conan Doyle. She knows, too, that this is Doyle’s bold and precise penmanship; the Lilly Library owns numerous letters written in his hand. And although the full provenance of the letter fragment, which has been in the collection for decades, is unclear, she knows that it did not pass through Watson’s hands. He’s not real, either—unless, that is, you are “Playing the Game.”

“A lot of Sherlockians would consider this—in a tongue-in-cheek way—to be a fragment of the actual letter that was found at Reichenbach Falls,” Dowell explains, using the nickname Holmes aficionados have adopted for themselves. “When Sherlockians ‘Play the Game,’ they are basically pretending that Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson were real people, and that Arthur Conan Doyle was their literary agent.” This belief in a living, breathing Holmes has been around almost as long as the stories of his crime-solving adventures have been; Doyle was regularly asked where to find 221B Baker Street, the address of the London flat where his fictional detective resided (which didn’t exist then, but does now, as the Sherlock Holmes Museum). The idea of “Playing the Game”—embracing and building on the world Doyle had created as a pseudo-reality—emerged not long after and was formalized with the creation of the Baker Street Irregulars in 1934.

“It was the first official fandom in the world,” says Maria Fleischhack. “I don’t think there was any kind of group that was dedicated to this kind of engagement with a literary text before that.” Fleischhack is a lecturer at Leipzig University in Germany, where she studies Victorian literature, including the stories of the iconic detective. She’s also one of the founders of the Baker Street Babes, an all-woman group of Sherlockians bringing a new perspective to “the Game,” which got its start in predominantly older, white, male circles.

“Playing the Game” is ultimately about connection, Fleischhack says: “There’s quizzes, there’s toasts, there’s drinking—a lot of drinking—and a lot of socializing. Interestingly, one of the elements that is so important is this friendship between Watson and Sherlock Holmes, which translates into friendship between the people who meet up to talk about these stories. This is not an academic society. It’s people who meet to talk with friends about their favorite friendship couple.” (But you will also find many of the same academics who attended serious literary conferences on Arthur Conan Doyle gathering to “Play the Game.”)

Though Doyle may not have anticipated that readers would form such an attachment to Holmes and Watson, Fleischhack believes the author’s writing style fostered this fandom. Doyle’s imaginary detective tales were set on the real streets of London and were often almost contemporaneous with their serialized publication. A 19th-century reader might discover she had walked on the same street Doyle described Holmes strolling down—on the same day he did. Doyle also—intentionally or accidentally—introduced unexplained inconsistencies in the fictional world, and hinted at untold stories. Was Watson’s war wound in his arm or in his leg? (Or both? Or neither?) What was the deal with the “giant rat of Sumatra,” a story, Holmes says in The Sussex Vampire, “for which the world is not yet prepared”? It’s like Doyle was seeding a modern form of fandom, and these are the types of things Sherlockians still debate today.

To explain the enduring appeal and countless adaptations of the detective’s stories, Fleischhack likens Holmes to another fictional creation that has inspired widespread obsession: The Avengers. “He’s like a superhero,” she says. “But he’s just human enough. He’s someone that you want to exist in the world.” Though the letter in Lilly Library is, correctly, credited to Doyle, Sherlockians want it and the sentiment—bidding adieu to dear Watson—to have come from the hand and mind of Holmes himself.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook