How It Came to Be That a Shark Dined on a Pterosaur

It’s fun to imagine it leapt out of the water like a torpedo—but unlikely.

The Pteranodon could be imposing, majestic creatures: flying reptiles with pointy skulls, wingspans of up to 18 feet, and, well, lean frames that typically weighed in at about 100 pounds. Not hefty, but you wouldn’t want to run into one in the Late Cretaceous equivalent of a dark alley. Unless you were a shark, like the one that somehow lodged a tooth in a Pteranodon neck about 70 million years ago.

The finding is detailed in a new study, published in the journal PeerJ. It offers a surprising entry in the well-stocked Pteranodon fossil record. Though more than 1,100 Pteranodon specimens have been documented, only seven of them bear marks of predation. This is the first case in which the predator is the Cretoxyhrina mantelli shark, a species roughly comparable to today’s great whites, says Mark P. Witton, a research fellow at the University of Portsmouth and an author on the study.

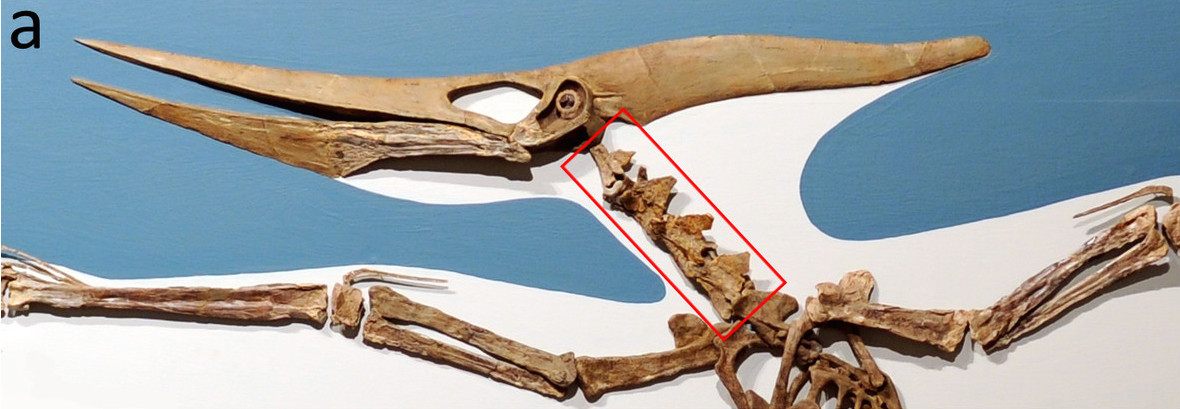

These sharks were no less impressive than the Pteranodon—big and fast, with sharp teeth and a big appetite. What makes the discovery more remarkable is that this shark appears to have been quite young (about eight feet long) at the time it bit into the flying reptile. Its tooth, says Witton, is about an inch long, and usual Cretoxyhrina teeth can be three times as big. The fossil itself is not a new find—it was excavated in the Smoky Hill Chalk region of Kansas in the 1960s, and has been on display in the Los Angeles County Natural History Museum for years—but the novelty of the tooth inspired the researchers to take it back out for further study.

It’s clear that this was the result of a bite, and that the tooth and neck did not randomly end up together in the ground, because the tooth is wedged neatly between the vertebrae. Contrary to other reports of the study, however, there is no evidence that the shark leapt from what is called the Western Interior Seaway (the inland sea that used to split North America down the middle) and grabbed the pterosaur in mid-flight. Far likelier, says Witton, is the possibility that the reptile was hovering close to the water, or maybe even swimming, when the shark grabbed it. It’s also possible that the pterosaur was already dead, and the juvenile shark just scavenged a free meal floating on the surface.

There’s no way of knowing for sure how it happened, but it’s pretty exciting even without a dramatic, teeth-out leap from the water. Any meeting of these prehistoric behemoths—with fossil evidence to prove it—is exhilarating to imagine.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook