The Precious, Precarious Work of Queer Archiving in the Pacific Northwest

Local legacy-keepers are working to ensure that the histories aren’t lost or forgotten.

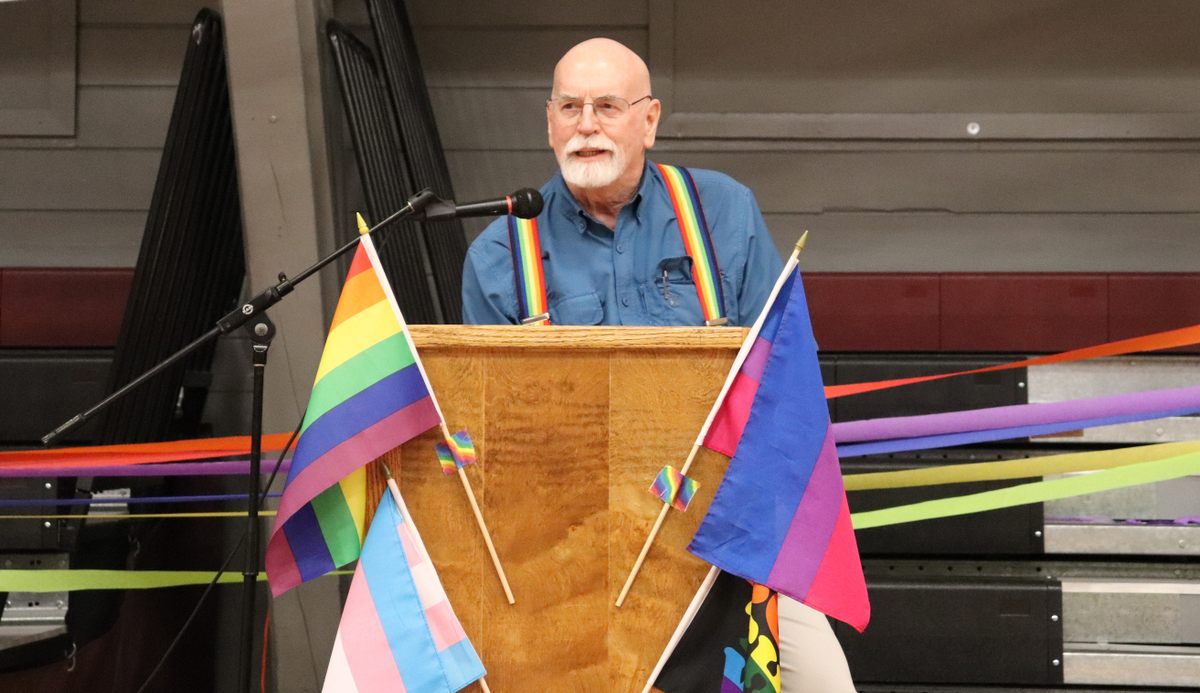

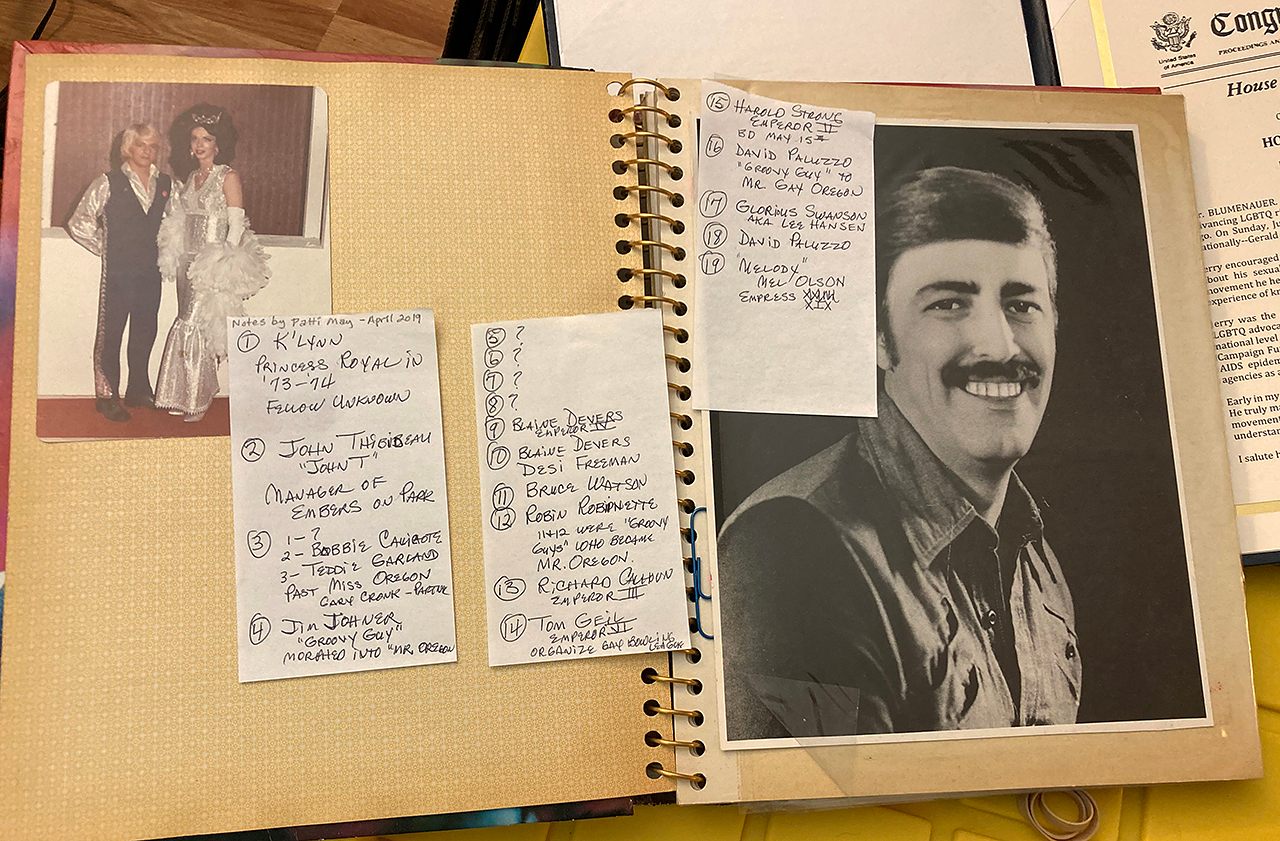

On a spring evening in 2019, Robin Will arrived at the Q Center, an LGBTQ+ community space in north Portland, with two heaping armfuls of scrapbooks from Jerry Weller, the late activist who helped spearhead the 1970s movement for gay liberation in the Pacific Northwest. Will was meeting up with four other community elders, all of whom witnessed the movement firsthand and many of whom appear in the photos tucked into the books as friends or co-conspirators of Weller. Slowly, the group began to chip away at a monumental task: identifying everyone pictured in the pages, preserving their legacy for generations to come.

Fueled by coffee and cookies, the five of them spread Weller’s scrapbooks across a huge wooden table and started poring over the images: local drag show snapshots; a smiling winner of Mr. Gay Oregon; scenes of queer folks marching arm in arm; faded portraits of friends and lovers long past. The photographs were a window into a history only partially documented, and it was now time to rescue each face from obscurity. “It’s time-consuming,” Will says. “It’s like if you were to sit down at grandma’s house with five of your great aunts and ask them to identify who’s in this picture, who’s in that picture, and then transcribe their conversation and make sure your text matches each photo.”

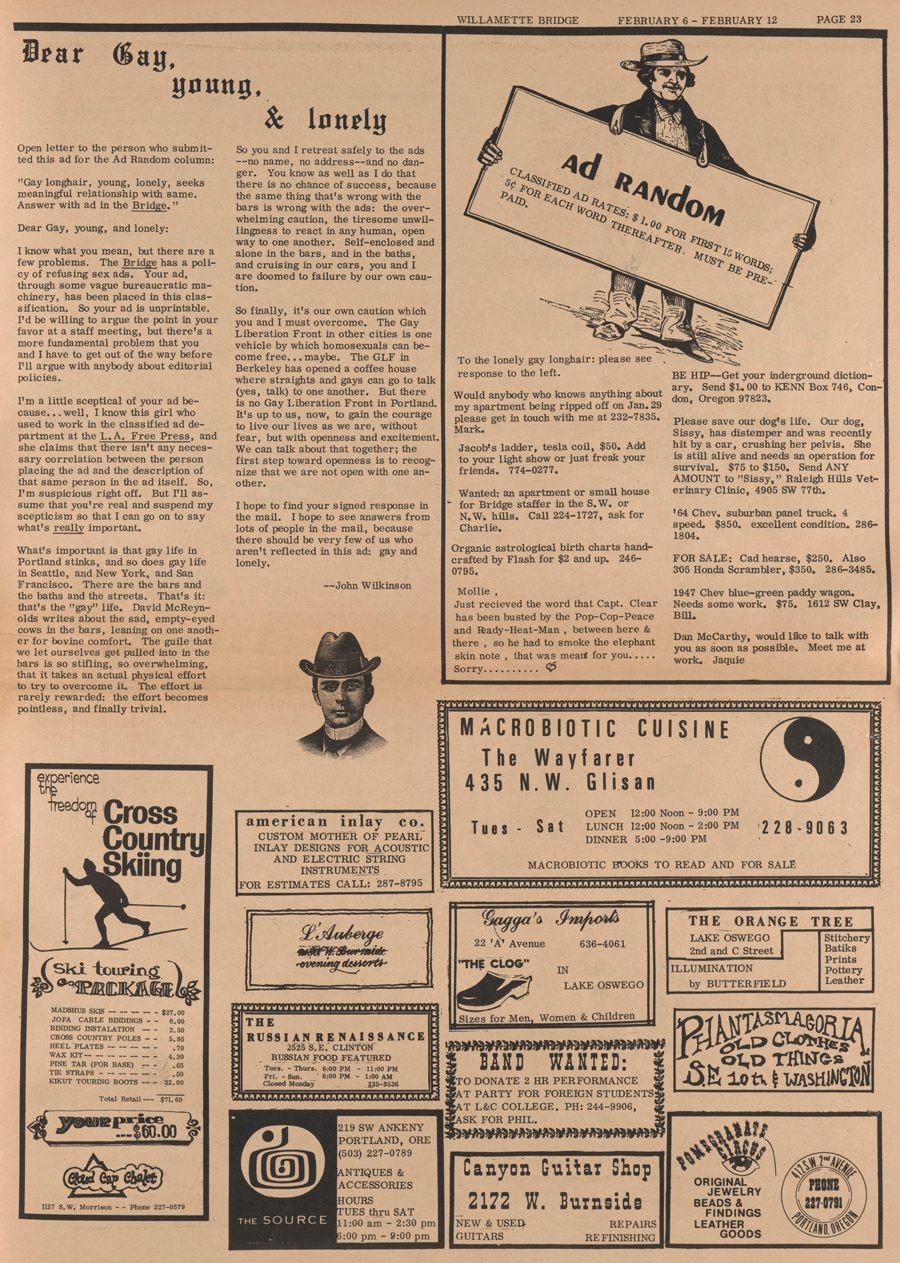

Weller’s scrapbooks span decades and document events both commonplace—like local drag shows—and extraordinary—such as founding of the Gay Rights National Lobby, which merged with the Human Rights Campaign in 1985. This is typical of Will’s work as president of the Gay and Lesbian Archives of the Pacific Northwest (GLAPN). The process of contextualizing these artifacts is intimate and painstaking, and often relies on the deep knowledge that can only come from folks who were physically present way back when.

Will doesn’t leave his work at work—his condo is a treasure trove of memorabilia that has been salvaged, but not yet catalogued or shared. He has boxes of ephemera tucked away in closets, and his desk and kitchen table are often covered in old photographs and scrapbooks. He lives alongside the physical archive, or whatever portions of it he hasn’t yet handed over to the Oregon Historical Society, which manages the collection.

Will is particularly precious about these objects because they are tangible proof of a history he lived through—one at risk of being lost over the next few decades, when there will be few people left who witnessed it firsthand. This is the inherently precarious nature of grassroots queer archiving: Much of the gay liberation movement of the 1960s, 70s, and 80s was sparsely documented by mainstream institutions, so unless organizations like Will’s capture it and describe it while the stewards are still alive, the history could very well disappear.

“If we don’t at least make an effort, a certain amount of this stuff is never going to see the light of day,” Will says. “People are going to throw it away because they’ve got no idea what it is. Or, even worse than actually looking at it and throwing it in a dumpster is just clicking on a folder and saying, ‘Delete,’ and then it’s gone forever.”

Archivists are always racing the clock and crossing their fingers, hoping that they encounter artifacts in time and that they’re able to access what they find. Technological barriers can sometimes get in the way. “I have an old WordStar terminal with someone’s thesis on it that people consider lost because only serious tech geeks know how to translate that,” Will says. “Most companies threw the terminals away, and I think in general the shelf life of technology is not long—they deliberately make it obsolete so that you have to update it. It’s like the Tower of freaking Babel or something.”

Queer archives are uniquely vulnerable in several other ways, too: Most operate on a shoestring budget, many with facilitators who are understandably skeptical of help from the government or mainstream institutions, both of which could potentially provide financial support. Queer archivists also confront the problem of erasure—materials being discarded out of bias, or because the current custodians simply don’t recognize the objects’ value. The family of Will’s high-school girlfriend encountered that problem: After the death of an aunt and her “friend,” the family found documentation that the pair had been underground leaders in their lesbian community of the 1940s and 50s—but, having no use for the papers, the relatives threw them away.

Apart from GLAPN, there are other stewards of queer history in the Pacific Northwest. In Seattle, the University of Washington Libraries’ Special Collections is home to oral histories from the Northwest Lesbian and Gay History Project, and some of their artifacts also live at the Museum of History & Industry. Anne Jenner, the Pacific Northwest Curator for Special Collections at the University of Washington, hopes to establish an official LGBTQ collection. That hasn’t happened yet, but there is an archival resource page. Queer history is “a challenging history to capture—it’s so vast, so multigenerational, and there’s no one single entity that represents all of it,” Jenner says. She also sees the present moment as a particularly important time for archives that collect these histories. “In the past eight years since I’ve been here, more and more collections are coming in, as LGBTQ folks are aging and moving out or downsizing. Also, many people in the community feel that it’s safe to share now in a way that it wasn’t before; making their stories accessible to the public doesn’t necessarily pose the same risk as it did in the past.”

The painful irony is that, even once these histories are successfully rescued and archived, there still isn’t much of a place for them in mainstream history books. Many kids aren’t learning this stuff in school, and pop culture glosses over much of it, cherry picking details for ad campaigns and movie scripts while ignoring larger contextual details. (Amazon’s Transparent, for example, exposed viewers to some trans talking points but failed to cast a trans character or diversify its depiction of queerness, and ultimately collapsed amidst sexual harassment allegations against its lead actor, Jeffrey Tambor.)

That’s not to say, however, that some young folks don’t understand the importance of a collective queer history: Many do, and organizations like the Lesbian Herstory Archives (LHA) exemplify how to successfully share it. The LHA has scads of volunteer opportunities, events, and a collection that prioritizes accessibility. And its physical location in Park Slope, Brooklyn, feels like a home away from home, suffused with the smell of brewing coffee and old books. “To stand there and be able to say, I’m surrounded by lesbian history—it’s a really singular experience,” says Julia Rosenzweig, who volunteers at the LHA and works for the Curve Foundation, which publishes Curve, America’s best-selling lesbian magazine. “I think if you ask the average person, they might say, ‘Oh, [archives are] only for researchers.’ But I think that the LHA are really approachable. It’s nice to have a space that’s just for us and our history. It has so much enduring value.” The community that Rosenzweig describes is exactly the kind that Will, Jenner, and other organizers like them hope to foster.

Much like New York City, the Pacific Northwest is home to some of the richest queer history in the country—and that means that, for Will, there’s a lot on the line. Back in his apartment, some of the people in Jerry Weller’s scrapbook pages will forever remain unidentified, and thus lost to history. Other figures won’t make it into Will’s stewardship at all. Their photos, and the stories they hold, will end up in the dumpster. But Will’s doing the best he can to rescue them. His efforts are emblematic of the kind of scrappy, DIY ethos that is the backbone of queer archiving—and through them at least a partial queer history continues to be saved.

This story originally ran in 2021; it has been updated for 2023.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook