The Return of Purple Straw, an Iconic Southern Wheat

It has a whole team of champions working on its comeback.

After the American Revolution, the newly-formed United States faced yet another battle. Goods on British ships harbored the notorious Hessian fly and rust disease. Both spread quickly, obliterating most East Coast wheats. At the same time, farmers began noticing that their soil had been exhausted from excessive tobacco and corn growth. But a certain strain of wheat came to the rescue: purple straw.

This grain, from the Virginia Piedmont region, was both pest-resistant and grew quickly, making it extremely reliable. According to Dr. David Shields, a Carolina Distinguished Professor and food historian, “purple straw was a wheat a farmer could trust year after year.” Many also found its honeyed, nutty taste to be perfect for whiskeys and pastries, especially biscuits. In fact, purple straw is believed to have been one of the first biscuit flours.

Until fairly recently, purple straw was a star Southern wheat, known far and wide for its stunning lavender-tinted stalks and delicious baking characteristics.

But the farmers of yesterday would be astonished to learn that their precious grain has since become nothing more than culinary lore. This grain lost its flair during the 1970s when hybrids that promised to produce higher yields took over. While not fully extinct, purple straw became extremely hard to come by. That is, until Shields and Glenn Roberts, the founder of heirloom grain grower Anson Mills, set out to restore this precious purplish crop.

The duo had previously worked together to restore the once-famous Carolina Gold Rice to prominence, and decided to combine their knowledge of heirloom grains once more to locate this fascinating variety. Shields, who was researching traditional Southern biscuit flour when he first learned about purple straw, was particularly intrigued by it due to its historical longevity. “Purple straw was one of the longest enduring wheats and one of the only durable commodity grains that shaped the cuisine of a region,” he explains. “It was the standard for the longest period of time.”

During their search, they found a few Amish farms that had seeds stored away, but even the farmers only owned a minuscule amount of the grain. Their quest was also complicated by the fact that purple straw went by several different names depending on the region. In Alabama, it was called Alabama bluestem, whereas James Anderson, the 19th-century farm manager at George Washington’s Mount Vernon estate, called it “red straw.”

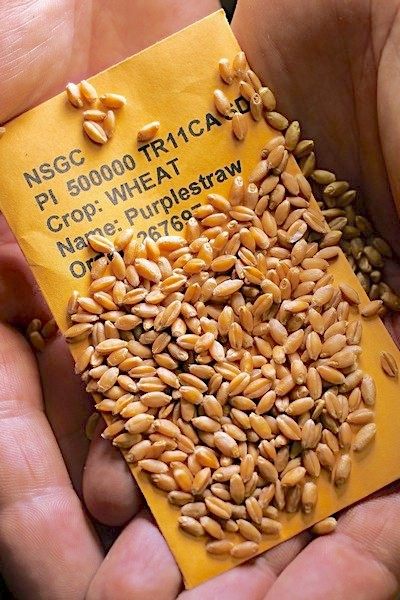

Their efforts finally led them to Idaho, where the U.S. National Plant Germplasm System (NPGS) had quietly stored away several purple straw seeds from the early 20th century. Some seeds were also acquired from California’s Sustainable Seed Company’s heirloom collection. In 2015, Shields and Roberts planted the seeds at South Carolina’s Clemson University, where they have been monitored ever since.

One Clemson scientist rigorously testing purple straw is Richard Boyles, a plant breeder and geneticist. Boyles notes that purple straw was very resistant to 18th-century diseases but succumbs easily to a variety of modern issues, particularly leaf rust. By crossing it with soft winter red wheat cultivars that have similar traits, he’s hoping to provide purple straw with protection from these current problems.

Boyles explains that the five-foot stalks require little care once planted, but desperately needs one thing. “Vernalization is very important,” Boyles emphasizes. “There needs to be enough chilling hours.” The future may not be cold enough to give the seeds energy to produce flourishing blooms. And while purple straw will still grow if vernalization is unsuccessful, the stalks will end up looking like long grass blades and won’t produce any grain.

There’s a lot of interest in a successful purple grain industry, especially in the South. Some distilleries are hoping to blend the grain in their whiskeys, thanks to its low gluten content. And numerous chefs aspire to use the flour for pastries. One such chef is biscuit-making icon Scott Peacock, who has been captivated by the wheat’s potential since 2014.

Peacock, who also has a strong interest in horticulture, wanted to join the restoration effort. In 2015, Roberts entrusted three tablespoons of seed to him, a substantial quantity seeing that this was an almost vanished strain.

Peacock planted about two teaspoons on a local organic farm near his home in Marion, Alabama, and harvested eight cups of grain to keep planting. Peacock fondly recalls the wheat having a fragrant, nutty aroma that drifted through the field each afternoon. He also observed that the birds oddly adored purple straw. During the first year, Peacock would see countless avians happily pecking away at the grain—so much so that he had to use cages and nets to protect it.

After three years of work, Peacock’s purple straw project came to a quick end after a neighboring farm spent a day crop-dusting their plants. The pesticides drifted over and within minutes, the toxins overwhelmed the delicate stalks. Peacock wasn’t deterred and tried planting the seeds once more in his backyard, only to get a phantom harvest—where the stalks appear to be bountiful but instead have empty heads without any grains.

Peacock has yet to try purple straw flour. His dream is to someday grow just enough to make at least one batch of biscuits with it. “Purple straw has shifted my appreciation for what it takes to have a cup of flour,” he says.

Demand is steadily rising, but you still won’t find purple straw in grocery stores. If you truly desire some, there’s limited 2.5-pound flour bags available from Barton Springs Mill in Texas, which has grown purple straw for the last three years. Only recently did Barton Springs begin producing enough seed to sell small batches of this Colonial-era flour. But both flour and the grain itself remain rare. “Seed availability is an issue,” explains Shields. “When there’s a commercial seed supplier, then purple straw will have a steady future.”

Justin Cherry, owner of Half Crown Bakehouse and Mount Vernon’s resident baker, is eager to use the flour once it’s widely available. “The milled flour has a lovely white color and the flavor tastes earthy and golden,” he says, also noting that its low gluten content and texture make purple straw perfect for cakes and 18th century-style shortbread. “When baked, there’s a very aromatic malty note released.”

There are even hopes that this heritage grain will grow at Mount Vernon once more. In 2021, with the help of Roberts of Anson Mills, Cherry and Mount Vernon’s horticultural staff planted a small plot of the wheat on the historical estate, maybe the first in over 200 years. The grain will likely be harvested this month and its seeds will be saved for future plantings.

As more become acquainted with the grain and its distinctive qualities, there’s hope that purple straw could make a comeback where it was once cherished the most. Considering how passionate its champions are, though, it’s only a matter of time. “It’s deeply rooted in Southern culture, but many just don’t know it,” says Peacock. “Everything about it is beautiful.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook