Eating Like an Explorer Once Called for Plenty of ‘Portable Soup’

Sailors relied on the ration for centuries.

When British explorer and Royal Navy captain James Cook set sail aboard the HMS Endeavour on August 26, 1768, for an expedition around the Pacific, he brought along 18 months of provisions. These included pigs, poultry, a goat for milking, and a large supply of portable soup.

Also known as “pocket soup” or “veal glue,” the latter became a breakfast staple—often reboiled with celery and oatmeal, or mixed with hot water and green pea flour to create an edible porridge—among the ship’s officers and crew. Each sailor would get a daily ration of the soup, though not because they enjoyed the taste. On long voyages characterized by tiny quarters and rampant scurvy (caused by a lack of Vitamin C), Cook believed portable soup to be one of the navy’s best weapons of disease prevention.

“Think of portable soup as the 18th and early-19th century version of bouillon cubes,” says Suzanne Corbett, co-author of A Culinary History of Missouri: Foodways and Iconic Dishes of the Show-Me State,“but probably with a lot more flavor than those little aluminum-wrapped packages.” Basically, the process involves slowly boiling down animal bones, such as leg of veal or beef shank, to create a broth, then removing the meat, cooling and straining the remaining broth, and reboiling it. Eventually, the broth becomes sticky and gooey like gelatin.

“You then dry it out further and it turns almost into a plastic,” says Corbett. The result is an intensely meaty and rubbery sort-of stiff jelly (one with a glue-like, almost adhesive consistency) that can be cut into pieces or sliced into “cakes,” then stored in a cool, dry place for months, if not years. “When ready you can just add water and it becomes soup or a base for other things,” she says.

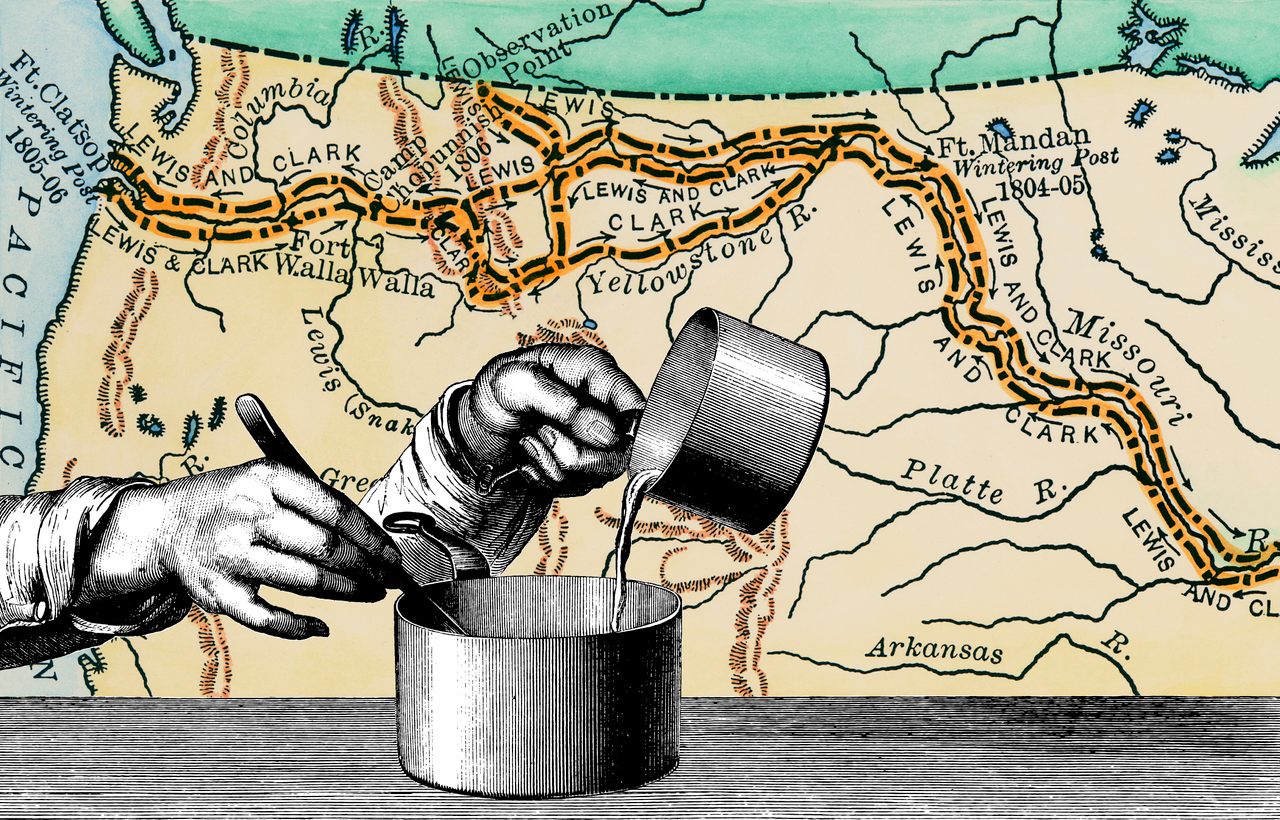

Portable Soup was once all the rage among American and European travelers, militaries, and seafarers—a compact and easy-to-preserve food that accompanied some of the most well-known explorers and expeditions of its era: from Captain William Bligh’s ill-fated journey aboard the HMS Bounty to Lewis & Clark’s early 19th-century expedition across the United States to explore the Louisiana Purchase. With the bulk of its calories from protein (a nutritional profile of Ann Shackleford’s 18th-century portable soup recipe, which appeared in The Modern Art of Cookery, lists 62 percent protein calories), portable soup could be eaten “neat” for substance or combined with vegetables or foods such as sauerkraut for added nourishment.

But it’s extremely time-consuming and arduous to make. In fact, the process of boiling down high-collagen cuts of meat into gelatin and then scooping out the meat, bones, and gristle before reboiling the broth (to reduce its volume) is an all-day procedure, one that can take up to 12 hours. Still, chances are that you’ve started the process of creating portable soup in your own kitchen without even realizing it.

“When you make a broth with a bone and you cook it long enough,” says Linda Duffin, a food writer and owner of Mrs Portly’s cookery school in Suffolk, UK, “what happens is all the collagen that’s in the bone marrow leeches out into the flavor liquid. All that collagen is actually gelatin. You’ve probably seen this if you put a roasted chicken in the fridge, and the next day you take it out and there’s jellied juice around it. That’s what it is.”

Duffin says that the same thing occurs with pig’s feet—a typical portable soup ingredient. “Calf’s foot jelly was a very popular food for sick people back in the day,” she says, “because it was packed with protein and easy to digest when you melted it back into a liquid.”

But while portable soup became something of a staple food by the 1700s, its origins are decidedly murky. In her 2010 book, Soup: A Global History, author Janet Clarkson writes, “There are many ridiculous claims as to the ‘inventor’ of portable soup, but it is most likely that it developed simultaneously in as many places as there are pots of broth to boil almost dry.”

One of the earliest written records of portable soup stems from the late 1500s, when the English agricultural writer and inventor Sir Hugh Plat scribbled down a recipe among some of his unpublished works: “[Portable Soup] is made from ‘neats feete & leg of beeff … boiled to a great stiffness.’” Plat then suggested adding a hint of isinglass—a form of collagen that comes from the dried swim bladders of fish—to make the dehydrated food stiffer, as well as rosewater for scent and saffron for color.

By the 1600s, portable soup was showing up seemingly everywhere. French scholar Antoine Furetière wrote about it in the pages of his Dictionnaire universel, published posthumously in 1690, while British recipe compiler Ann Blencowe included basic instructions for portable soup in her own 1694 cookbook, calling for “boiling two calves’ feet until they produced a sort-of ‘veal glue.’”

Several decades later, English culinary writer Hannah Glasse even tried elevating the dish into something a little more lively, enhancing her own portable soup recipe in 1747’s The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy with anchovies, cloves, mace, pepper, onions, marjoram, and thyme, not to mention “the dry hard crust of a two-penny loaf.”

Still when it comes to portable soup’s mass-production, perhaps no one was more instrumental in commercializing the dehydrated food than 18th-century London tavern keeper Elizabeth Dubois. Using what appeared to be an innate entrepreneurial skill set, Dubois took out advertisements in the city’s General Advertiser touting her portable soup as “useful on Journies or at Sea” and “not disagreeable to chew when Hunting.” Then in 1756, Dubois won a contract to manufacture portable soup for the British Royal Navy, where it became a staple on long-haul sailing vessels.

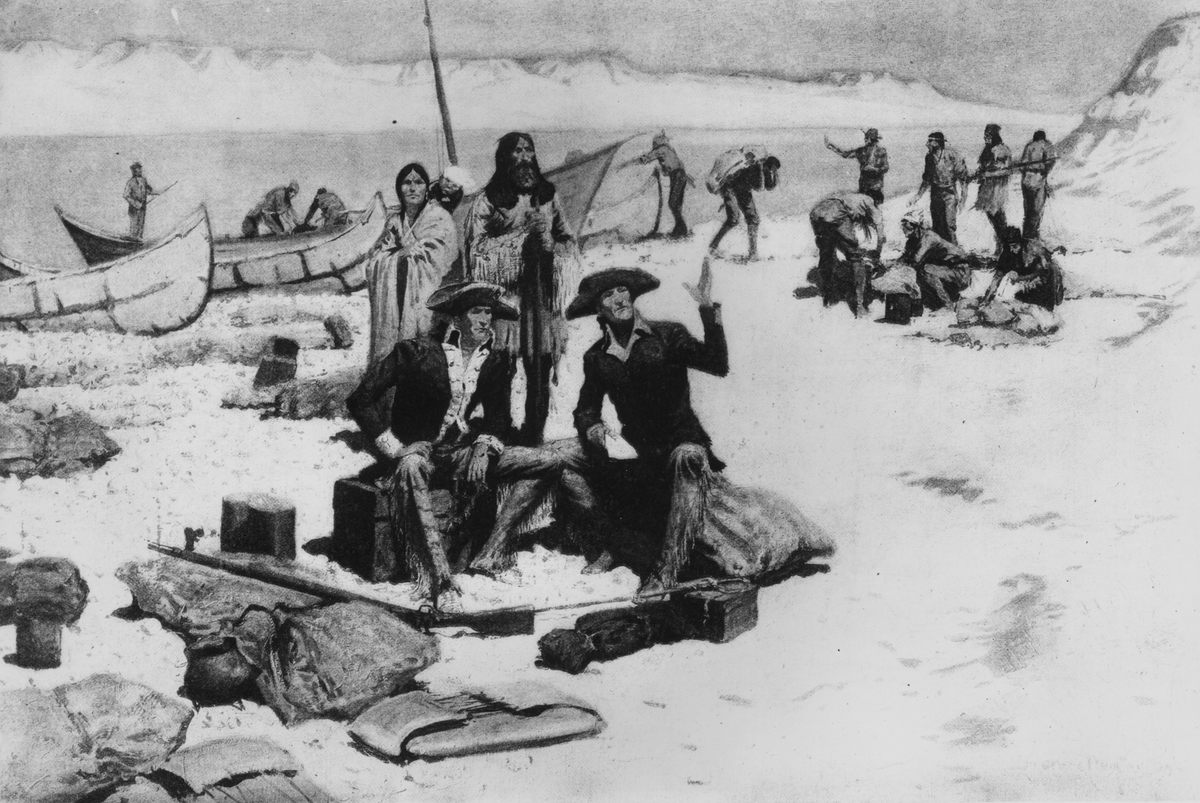

Despite its ubiquity, portable soup was hardly anyone’s favorite dish. For example, when American explorer Meriwether Lewis set about gathering supplies for his 1804-1806 expedition with William Clark, he considered portable soup an essential. Lewis secured 193 pounds of it, all prepared by a Philadelphia cook named François Baillet (and then stored in 32 tin canisters), for a total of $289.50. But the Corps of Discovery only ever consumed the soup when food was scarce: Most notably, during a grueling 11-day trek across the Bitterroot Mountains—more than 15 months into their journey.

With a less-than-desirable taste already prohibiting its popularity, portable soup was about to encounter a new series of hurdles.

In 1815, the senior medical official with the Royal Navy, Sir Gilbert Blane, wrote that portable soup’s effectiveness in preventing scurvy wasn’t so reliable after all. Around the same time, French chef Nicolas Appert perfected the art of airtight food preservation, and canned foods became the new go-to among sailors. Then came Baron Justus von Liebig, a German organic chemist who figured out how to concentrate beef solids into an extract. By the end of the 1800s, the Leibig’s Extract of Meat Company was manufacturing his industrialized bouillon cubes in bulk, usurping portable soup as the dehydrated stock of choice. Cubes from companies Maggi and Knorr followed right alongside them.

According to the Food Timeline, “Portable soup in its original form survived, at least in recipe books, into the 19th century.” However, its legacy lives on at Britain’s National Maritime Museum, which has a cake of portable soup that’s thought to be from Cook’s own provisions. While not on display, it can be viewed on the Royal Museums Greenwich website. Though cracked and leathery, the dried soup appears much like it might have more than 250 years ago. It’s a testament to the longevity that kept portable soup, and so many sailors, afloat for at least a half-a-century.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook