The Mysterious Norwegian Art of Painting on Dead Fish

No one knows how artists pulled off a trick over 100 years ago.

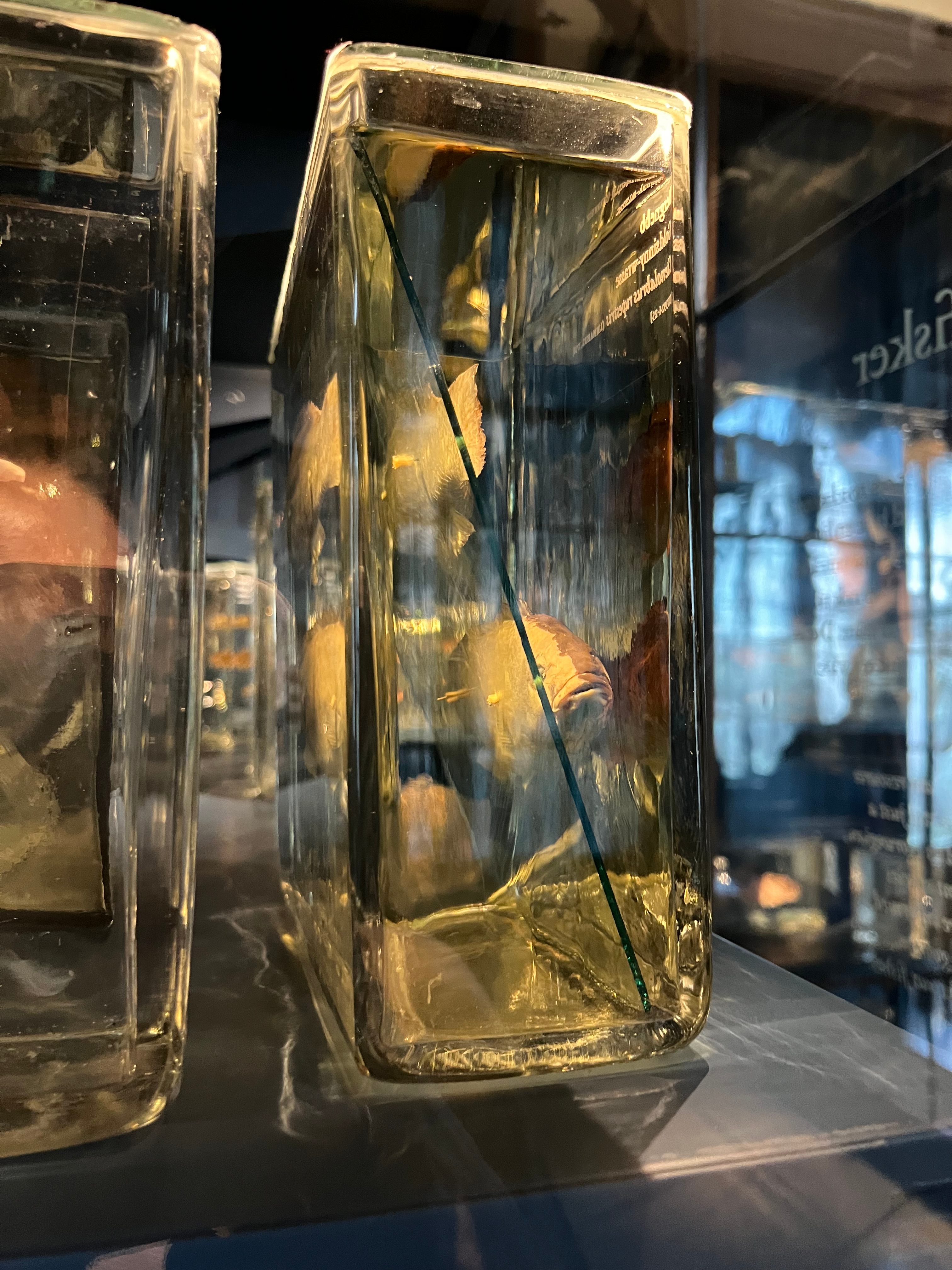

An Atlantic cod is suspended in alcohol in a clear, rectangular container. It’s one of a smattering of specimens, all floating on shelves beneath the massive ribs of long-dead whales. This room in the University Museum of Bergen, a natural history museum on Norway’s western coast, is purpose-built to hold marvels from the sea. Cod isn’t as startling or unfamiliar as the fish that dwell in the ultra-dark deep and look alien to our landlubbing eyes. Yet something about many of the fish on these shelves is wondrously strange and enduringly mysterious.

For fish in museum collections, the cost of an afterlife on land is a squandered splendor, since the colors of their scales fade over time to a dirty gray or white. But many fish in the University Museum of Bergen are orange, brown, striped, or speckled—vibrant and vivid, as if the creature had only recently stopped swimming. Only on the other side, the part facing the wall, are the scales a pasty white. That’s not a coincidence. Around a century ago, someone painted the visitor-facing portions to look lifelike. But no one seems to know how the artist pulled it off.

When Terje Lislevand, an ornithologist in charge of the museum’s zoology collection, arrived at the museum in 2009, many of its creatures and crannies were in need of repair. Upon beginning the gig, Lislevand met a menagerie of taxidermy animals dirty and bleached from the sun, and whale skeletons cloaked in dust and debris. The main means of climate control had been opening and closing the building’s windows; over the years, little bits of rubber blew in from the street and settled on the bones.

The staff got to work cleaning and renovating the display spaces, offloading the sorriest-looking specimens, cataloging holdings, and combing through papers or deciphering labels on jars to figure out when and where the creatures were collected. But there was vanishingly little information about the fish.

“Even people who had been working at the museum and with these collections, they didn’t know what kind of paint they had used,” says Lislevand. “I don’t even think they knew who did it.”

Some alcohol had evaporated, and the liquid that remained had begun to yellow—still, many of the fish specimens looked great. “They are good representations of what the fish look like in life,” Lislevand says.

Lislevand suspects that the fish were painted soon after they died. The painter would probably have had access to color plates in natural history books, but Lislevand wagers that the artist was simply committed to close looking. “I think they tried to just repaint almost scale by scale the colors of that particular fish,” he says.

Whoever the artist was, however they did it, the project was brilliant. Pigments are finicky, susceptible to suffering in light and alcohol. Unfortunately for dead fish, museums have both. It’s simple enough to subdue the lights in display areas and keep fish that aren’t receiving visitors submerged in total darkness; those resting in storage facilities may be sealed, for instance, inside shadowy metal tanks. But in a museum, there isn’t a good way to avoid the risks posed by alcohol.

Many natural history museums preserve wet specimens in a two-step process. First, each fish is fixed in formalin (a formulation of formaldehyde), which binds to tissues and prevents them from breaking down. Next, the fish are plunged into alcohol, which staves off bacteria and fungi. With this double whammy, fish can last “for decades, 100 years or more,” says Todd Clardy, the collections manager of ichthyology at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, which uses this method for its three million fish.

The combination of formalin and alcohol keeps the fish intact, but contributes to the leaching of their colors. Museums often “sacrifice color so we have the specimen in good condition,” Clardy says. “We can’t have everything. I wish we could.”

Terrestrial creatures are no strangers to a postmortem zhuzhing. In natural history museums, conservators occasionally spruce up decades-old dioramas by applying airbrush dye to dulled fur. But there is no close equivalent for fish, and specimens start to dim pretty quickly; on some reef fish, hues begin to fade hours after death.

To capture data about color, museum teams often try to photograph collected fish as soon as possible—ideally, while the animals are still alive. This sometimes entails setting up a mini digital photo studio in the field, plopping a fish into a light box against a white or black background. “We don’t want to waste any time,” Clardy says. Time is precious because once color starts to go, there’s not a way to slow down its disappearance, Clardy adds. “The tropical fish that looks beautiful on the reef is just going to look brown when it’s in our collection,” he says.

The painter in Norway sidestepped these problems, even as they left a bunch of questions behind. Who did the work? It would be possible to hazard some guesses by determining who worked in ichthyology at the museum when the fish first went on view, but as far as Lislevand knows, no one has taken up this detective task. What paints and processes did they use? “It might have gotten lost, or it could be that they never thought it was interesting to write it down,” Lislevand says. “It seems like they thought, ‘Oh, everyone will know how to do this in 100 years, this is the only way.’” That hasn’t proved to be true.

Ruth Murgatroyd, a conservator at the museum, has wondered about whether these fish have kin in other collections. “It is not something I have ever come across at other museums and have reached out to a few colleagues and they also seem to find it to be something novel to Bergen,” Murgatroyd writes in an email. But recently, a colleague in Wales mentioned that they have some painted fish, too, and that they might exist elsewhere. For Lislevand, the mini mystery is a reminder about the importance of leaving a trail for future staff members. “It illustrates the point of documenting how you do things.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook