Our Sewers Speak Volumes. These Robots Are Ready to Listen

Sewer robots named Mario and Luigi are collecting data to analyze our health.

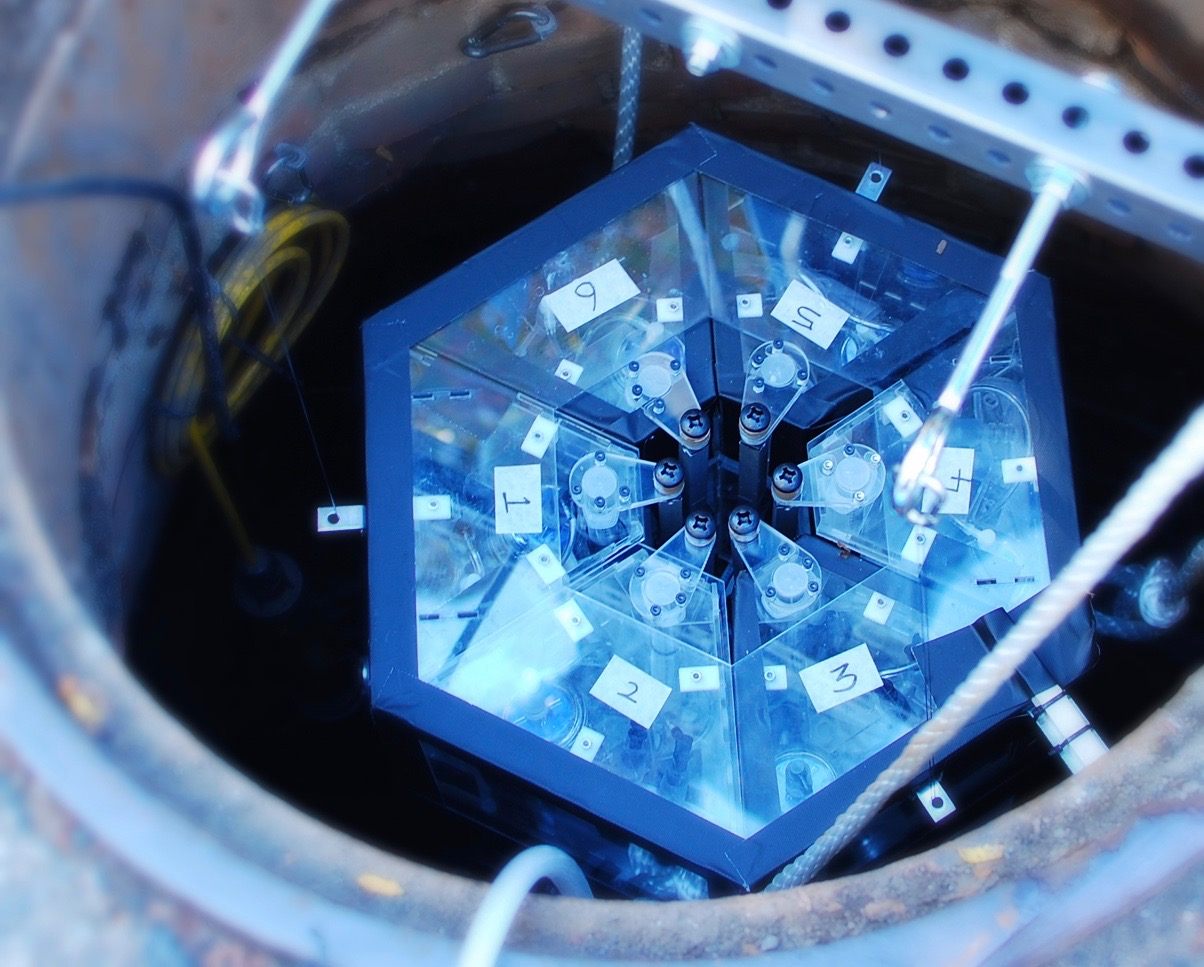

Mario, a sewage sampler robot descending into the underworld. (Photo: MIT Senseable City Lab)

When you think of the Super Mario Brothers, you might think of little mustachioed men shimmying up and down pipes.

Now think of Mario and Luigi shimmying right down into the sewers, to collect samples from the hodgepodge of waste that accumulates underground–sewers brimming with the tens of thousands of viruses and bacteria that make up a city’s collective microbiome.

Instead of pixelated plumbers, these Marios and Luigis are robots who descend into Boston’s sewer system to try and capture data on health and disease by sifting through the run-off from showers, toilets, and rain. The two robots are part of Underworlds, a project at MIT that is taking a closer look at the rich abundance of personalized waste that goes overlooked, sloshing out of sight beneath our feet every day.

The dark bowels of a city may have a lot to tell us. (Photo: Erik Mauer/CC BY-ND 2.0)

Yet Mario and Luigi and the team at Underworlds are aiming to turn “smart sewage” into a tool to predict outbreaks of viruses and disease (think influenza, gastroenteritis, dysentery) by collecting and analyzing biochemical information. By scrutinizing the refuse in our sewers, we can keep a finger on the pulse of entire populations.

The hope is that in the future, a community’s sewage will be able to inform us of the presence of illness, provide demographic data, and keep everyone one step ahead—predicting infections or pandemics before they break out.

The robots, designed and built at MIT’s SENSEable City Lab, replaced the team’s initial sampling method, which involved lowering a 20-foot pole with a bottle taped to the end into a manhole to scoop out sewage samples. It was messy, involving a pump connected at street level to a car battery to push the sewage up from below, according to Carlo Ratti, Director of SENSEable City Lab, and Newsha Ghaeli, a research fellow.

The team used a large peristaltic pump and car battery to manually collect samples before Mario and Luigi came along. (Photo: MIT Senseable City Lab)

The old collection method was then followed by a lengthy process in the wet lab, where the raw sewage was passed through a series of biograde filters to capture the DNA. “Playing with sewage was not that fun,” Ratti and Ghaeli explain over email. “Even when the sewage is flowing quickly you get a particular smell all the way to the street level!”

Hoping there was a more efficient, less smelly way to collect the data, the Underworlds team decided to check in with their colleagues in the computer science lab for help—and thus the sewer robots were born. Mario, the first prototype, and later Luigi, a second faster and slimmer prototype, were designed with the ability to preprocess any amount of raw sewage by filtering it on the spot.

This summer, the team is deploying 10 sewer robots across Cambridge and Boston in order to sample the sewage of multiple neighborhoods simultaneously. They are operated with a simple, battery-powered micro-controller, and will soon function within a GPRS system that will allow the bots to communicate with and be controlled by a central decision maker. They will relay real-time sewer data, such as flow and temperature, through a wireless cloud.

A closer look at Luigi—slimmer and more cost-effective than his brother Mario. (Photo: MIT Senseable City Lab)

Underworlds is planning to dispatch more Marios and Luigis to its planned operations in Kuwait, where they recently received a $4 million grant. Ultimately, cities can decide how many samplers they’d like to have in place. The team is constantly improving the prototype, and they’re far from finished. They’re still looking for ways to detect particular pathogens in real time, and will be continuing the pilot project through 2017.

They are also thinking about time-sensitive sampling—collecting data during “peak poop hours”—and they are continuing to filter, analyze, and decode all sorts of waste. Detecting organisms and viruses is not simple, nor always successful, but the team is feeling optimistic about its progress.

Our collective bowels clearly speak volumes. Mario and Luigi are ready to go out and listen.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook