Meet the ‘Comet Egg,’ Which Definitely Did Not Come From Space

Investigating the old myth that cosmic events can have a fowl impact.

The year 1986 was approaching, and earthlings were gearing up for a flyby from a long-awaited cosmic guest star. Anticipation was high, so much so that some people were wondering if the celestial visitor would wear out its welcome. “By the time Halley’s Comet swings past the sun … and heads back into the dim and distant reaches of its orbit, everybody on Earth may well be tired of hearing about it,” wrote Ruth S. Freitag, a senior science specialist at the Library of Congress, who compiled a bibliography of information about the comet a year prior.

That’s not the way it turned out. The comet, though predictable, has never failed to captivate. Named for English astronomer Edmond Halley—who analyzed its past visits and predicted its return around 1758—this particular “dirty snowball” is what’s known as a periodic comet, meaning that its orbit brings it around to us at regular intervals, leaving a bright, milky smudge across the sky. Sightings in 164 B.C. and 87 B.C. appear to have been recorded on on Babylonian tablets, and it was also embroidered on the 230-foot-long Bayeux Tapestry, which depicts the Battle of Hastings and England falling to the 11th-century Norman conquest. (There, it looks like a plucked sunflower cast on its side.) The comet has inspired generations of artists, chroniclers, scientists—and chicken owners.

Comets had long been associated with mysticism and maleficence—occasionally a bringer of luck, but more often a harbinger of war or misfortune. So there could have been an unsavory dimension to the more recent legend that whenever the comet shot past, some kind of extraterrestrial image would appear on the shell of a chicken egg.

This lore dates back at least to the 17th century, as Brian G. Marsden, late director of the Minor Planet Center at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, recounted to NASA. In December 1680, when a comet shot past overhead, a hen in Rome was said to have laid an egg spangled with a cosmic pattern. When word of the “wonder egg” spread, Marsden writes, the Paris Academy confirmed that “the event caused the hen to cackle extraordinarily loudly, that the egg was uncommonly large, and that it was marked … with several stars.” If the report was true, one French journal noted at the time, “it would not be the first prodigy of this nature that has appeared in Italy during eclipses or comets.”

The shape of a sun was said to have appeared on an egg in Bologna during an eclipse, and another “comet egg” reportedly turned up in Reno, Nevada, when Halley’s Comet soared by in 1910. When a county clerk, identified only as Mr. Fogg, stumbled out in his bathrobe at 3 a.m. to watch the comet, “he was puzzled to see his pet hen running around in the yard cackling and looking into the heavens,” the Reno Gazette-Journal reported. Fogg was, presumably, even more surprised the next morning, when he found that the hen had laid an egg “with a long tail on it,” seemingly modeled after the comet itself. This special egg was front-page news.

By the time 1986 rolled around, Thames Valley Eggs, a British producer, put out a call far and wide: Bring us your comet eggs. More than 350 people joined the publicity stunt, each claiming possession of an honest-to-goodness specimen. (No staining, drawing, or other shell-meddling was allowed.)

Officials from the United Kingdom’s Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food—tapped as judges—reviewed the entries, and weren’t convinced that any of the streaks or bands were cosmic, or even in any way remarkable. “Many of the markings on these eggs are fairly commonplace, resulting from excessive calcium deposits on the shell, or from irregularities in the chicken,” one said, in a press release.

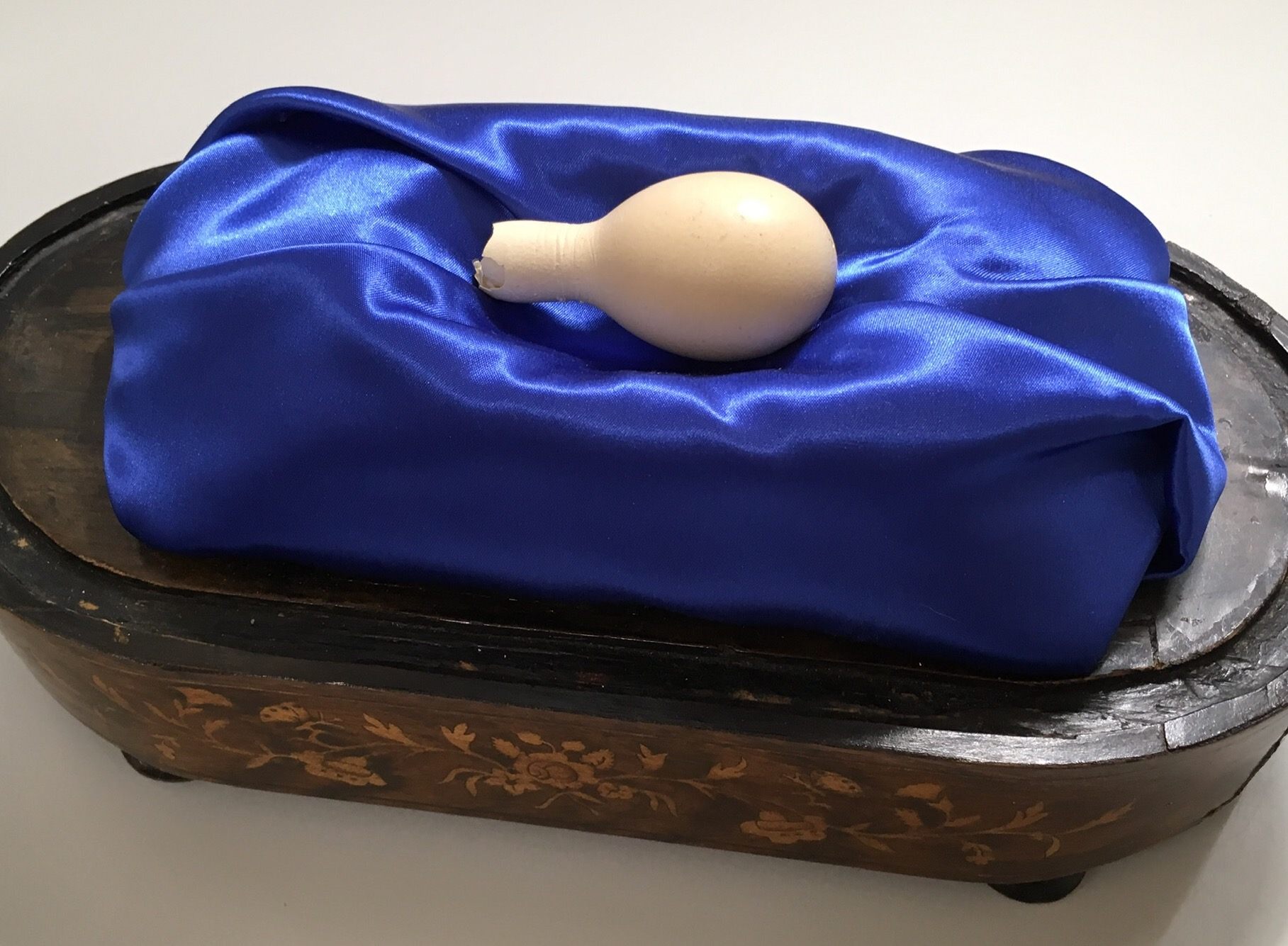

But they did declare a winner. Linda Franklin’s triumphant egg didn’t bear a stardust pattern, but it did have a bit of a tail, though it actually looked kind of like a skinny, palm-sized bowling pin, or a maraca. Franklin collected it near Studley, England, the Associated Press reported at the time, from “an anonymous hen with an odd affinity for astronomy.” She said she’d put her ₤5,000 winnings toward a car.

The egg traveled to London, where it’s now in the Natural History Museum, emptied of its contents and resting on a deep blue pillow beneath a bell jar. The museum has a vast trove of oological specimens—more than 200,000 clutches totaling 1 million individual eggs—but “this is somewhat of an anomaly in the collections,” says Douglas Russell, senior curator of birds’ eggs and nests. Russell is currently in the midst of a cataloguing project, and shared a photo of the egg on Twitter after finding it in a drawer.

Assuming that the comet didn’t have any direct connection to the egg’s shape, how did it come to look the way it does?

The shape of bird eggs varies across species, and by what’s going on in a bird’s life at a given time. Broadly speaking, eggs come in a gradient colors, sizes, and shapes, which range from spheres to ovals to teardrops. In 2017, a team led by Mary Caswell Stoddard, an evolutionary biologist at Princeton University, analyzed 50,000 specimens from 1,400 species, and plotted them on axes of ellipticity and asymmetry. The eggs laid by brown hawk-owls look almost perfectly round, like little white gumballs, while the speckled eggs of the least sandpiper are tapered to a point at one end. Writing in Science, the researchers reported that egg shape corresponds with birds’ flying ability, concluding that asymmetrical, elliptical eggs indicated a body structure that gave certain species a boost toward “high-powered flight” while “maintaining a streamlined body plan.”

An egg from a hen will never look like an egg from a sandpiper, but they can still get wonky. A bird may lay eggs with a surprising shape if she’s feeling stressed or sick—infectious bronchitis can affect the thickness and texture of hens’ eggshells, for instance—or if something is off in the oviduct, the stretchy tube the egg travels along. “A bird’s oviduct is a complex, dynamic place,” says Stoddard. “Sometimes things go wrong.” Stoddard says that while researchers “still have a great deal to learn about how egg shapes are generated,” she and her colleagues have proposed a biophysical model, suggesting that unusual shapes may arise because of changes to the properties of the egg membrane, or the pressure applied to it.

“What you’re seeing with this particular egg is something that’s gone drastically wrong,” Russell says. Franklin’s prizewinning egg “is a result of the egg being constrained during egg formation,” he adds. He’s not sure what caused this particular instance, but notes that constrained eggs are “relatively commonly seen in domestic fowl.” (They’re seen in other species, too, but humans are particularly likely to notice them in the species we breed and eggs we see often.)

Setting aside the gimmick of a comet egg competition, researchers really are curious about how animals respond to cosmic events. During the 2017 solar eclipse, for instance, they collected reams of data, and tapped citizen scientists to share their observations about how birds, insects, and other creatures behaved. Many of the people who shared their observations on the iNaturalist app’s “Life Responds” project, a collaboration with California Academy of Sciences, observed hens clustering together or roosters beginning to crow as the sun vanished. Some people who set out to document other animals’ responses ended up capturing human excitement, too, in roars of applause or shouting. In theory, it’s possible that the human frenzy around a celestial event—a comet, say—could startle a chicken and throw off the egg-laying process. The idea that witnessing a passing comet could induce a chicken to lay a comet-shaped egg “is probably science fiction,” but “we do know that stress can influence egg formation, because the egg’s journey down the oviduct can be altered,” Stoddard says. “Anything that can freak out the female at the point that she’s about to lay can cause problems,” Russell notes.

Russell isn’t surprised that people often look for oddities on the ground when something striking happens in the sky. “People like the weird, they like the obscure,” he says. “The idea that Halley’s Comet could cause a chicken to produce a comet-shaped egg is amusing to people, but these are perfectly normal anomalies that happen. It’s just that this time, it happened to look like a comet.”

Halley’s Comet will visit again in July 2061. If you have chickens, hey—it can’t hurt to check the coop.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook