The Nightmare of Sleep Paralysis Makes a Comeback in Modern Horror

Centuries-old superstitions about troubled sleep are reawakening thanks to scary movies.

This story was originally published on The Conversation and appears here under a Creative Commons license.

You wake up in the middle of the night. The room is dark except for the faint glow of the moon through your window. But something’s wrong. A weight presses down on your limbs, digs deep into the flesh of your stomach, and squeezes the air from your lungs. You try to move, but you can’t—all you can do is tentatively open your eyes.

A shadow of twisted, gangly limbs writhes above you. A looming head moves closer to your face. And just as your paralyzing terror threatens to burst you open, the monster retreats and you regain control over your limbs. You wake up. It was just a dream. Hopefully.

This is what it feels like to suffer from sleep paralysis, which is termed a parasomnia, and characterized by the sensation of a crushing weight accompanied by hallucinations of a malevolent presence. We now know that it has a scientific explanation: Paralysis is a natural part of sleeping that wears off before morning, but some of us wake up while it’s still in effect.

The history of the phenomenon, however, is one of suspicion and witchcraft. While our modern superstitions have dwindled, sleep paralysis is having a renewed grip on our imagination through a trend in recent horror movies.

Until the Renaissance promoted scientific evidence over religious superstition, it was commonly believed that troubled sleep was caused by malevolent witches. Many of the old names for sleep paralysis align with this idea: being “hag-ridden,” for instance, or of being attacked by a bewitched horse known as the “mara,” from which we get the term “nightmare.”

As such, bedroom rituals were as much about defending against witches as they were about winding down for sleep. People would wear necklaces of coral, or hang a fossil known as a belemnite over their beds, to protect them from being crushed by witches in their sleep. Stables, too, were adorned with talismans to guard horses from being possessed by witches intent on using them to trample sleeping victims.

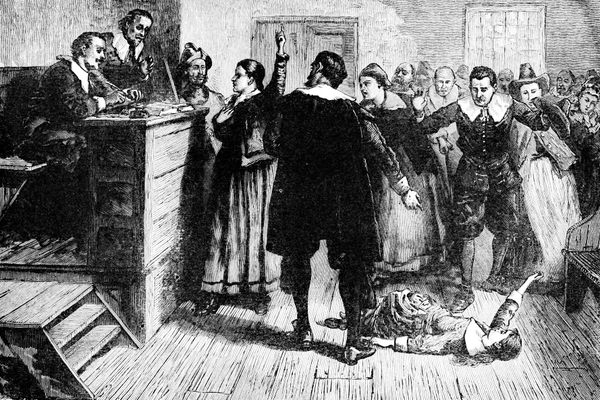

It has been 330 years since the infamous Salem witch trials, where 19 people were hanged on suspicion of being in league with the Devil. More than 200 accusations were made, and the court records are now digitized and held in the University of Virginia library.

When writing my book, Night Terrors, I accessed these papers, and recognized that many of the accusations described encounters with “witches” aligned to prevalent ideas of the cause of sleep paralysis. In the testimony of Richard Coman against Bridget Bishop on 2 June 1692 , he describes Bishop opening the curtains at the foot of the bed, and lying upon his body and crushing him so that he could not speak or move. Bishop was the first to be executed.

During the time of the Salem witch trials, however, a more rational explanation was being discussed in terms of scientific discovery that situated sleep paralysis firmly within the body of the sufferer. Belief in witchcraft, at least in terms of troubled sleep, started to dwindle.

There seems to be renewed interest in witch-trial superstitions in modern horror films. Recently, a variety of protagonists face monsters and demons while in that most vulnerable of spaces: the bed. In the 2014 film The Babadook, directed by Jennifer Kent, Amelia (Essie Davis) watches in paralyzed horror as the film’s titular monster skitters across her bedroom ceiling. Her mouth is agape in a silent scream as the Babadook drops like a spider on top of her.

Similarly, in Last Night in Soho, Thomasin McKenzie’s protagonist, Eloise, becomes pinned to her bed by the ghostly hands of murdered men. Other films are even using sleep paralysis as the monster, such as The Nightmare, a horror documentary depicting the parasomnia, and Andy James Taylor’s short film, The Nocnitsa in which a young woman is haunted by a shadowy presence creeping up her bed while unable to move.

It’s becoming increasingly noticeable—and there are a few reasons to explain the trend. Each presentation of sleep paralysis in film confuses the boundary between the hero and the “hag,” with the latter often being a product of the imagination and representing psychological turmoil.

In other words, the protagonist’s emotional troubles are made manifest through their sleep paralysis demons. Another factor is that it brings the monster of classic horror films into a much more personal and domestic space. It presents the idea that the villains we face in our sleep are of our own making.

Perhaps the most prevalent reason, though, is that sleep is now overanalyzed and too firmly rooted in neuroscience and discussions of sleep “habits” and “hygiene.” Cultural discussions of sleep have moved so far away from the creepy and the mysterious that it is now the role of horror films to remind us of the grip that troubled sleep used to have on our imaginations.

Sleep is now scrutinized under a harsh clinical light, but horror stories are increasingly restoring a more historic sense of darkness.

Alice Vernon is a lecturer in creative writing and 19th-century literature at Aberystwyth University.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook