How a Groundbreaking Pastry Chef Bakes Outside the Lines

A conversation with Natasha Pickowicz on cross-cultural inspiration and her upcoming cookbook.

THIS ARTICLE IS ADAPTED FROM THE JANUARY 15, 2023, EDITION OF GASTRO OBSCURA’S FAVORITE THINGS NEWSLETTER. YOU CAN SIGN UP HERE.

Toward the tail-end of the 19th century, American cake baking took a giant leap forward. The invention of chemical leaveners such as baking powder and in-home ovens meant that fancy cakes were no longer exclusively for those with full-time servants. No one knows who came up with the American layer cake, but these buttercream-crowned tiers quickly spread across the nation.

Although these cakes were decidedly different from their European counterparts, American bakers still tended to look across the Atlantic for cues. French patisserie was often seen as the gold standard of the genre, while fruit-and-nut-studded English “puddings” and rich German and Austrian baked goods made their way over through immigrant communities.

Patisserie has never been static. A glance at cookbooks over the decades shows bakers adapting to economic crises, wartime rationing, and the meteoric rise of Betty Crocker. Yet for generations, the archetypical American cake looked like the kind of stately tower seen on the covers of Gourmet magazine.

Don’t get me wrong: I love these as much as anyone. But there’s a whole world of desserts out there. One of the most exciting shifts in patisserie in recent years is seeing American bakers drawing inspiration from all over the globe. An American cake these days could as easily be flavored with ube or pandan as chocolate or vanilla, and bakers are just as likely to emulate a Hong Kong bakery’s mille-crêpe as a Parisian bakery’s gâteau.

Natasha Pickowicz has a long history of baking outside the lines. The three-time James Beard Award nominee has dabbled with ingredients ranging from worm salt to sunchokes in her innovative, thoroughly delicious desserts.

Prior to the pandemic, she was the pastry chef at Flora Bar and Altro Paradiso in New York. Since then, she’s become known for the ongoing pop-up series Never Ending Taste as well as her community bake sales, which have raised tens of thousands of dollars for Planned Parenthood and other organizations.

And while she’s tackled all sorts of pastry, it’s her layer cakes that have been turning heads and dropping jaws. The confections—which often come garnished with a garden’s worth of flowers and foliage—bear minimal resemblance to traditional American layer cakes. Rather, they feel like a new evolutionary step.

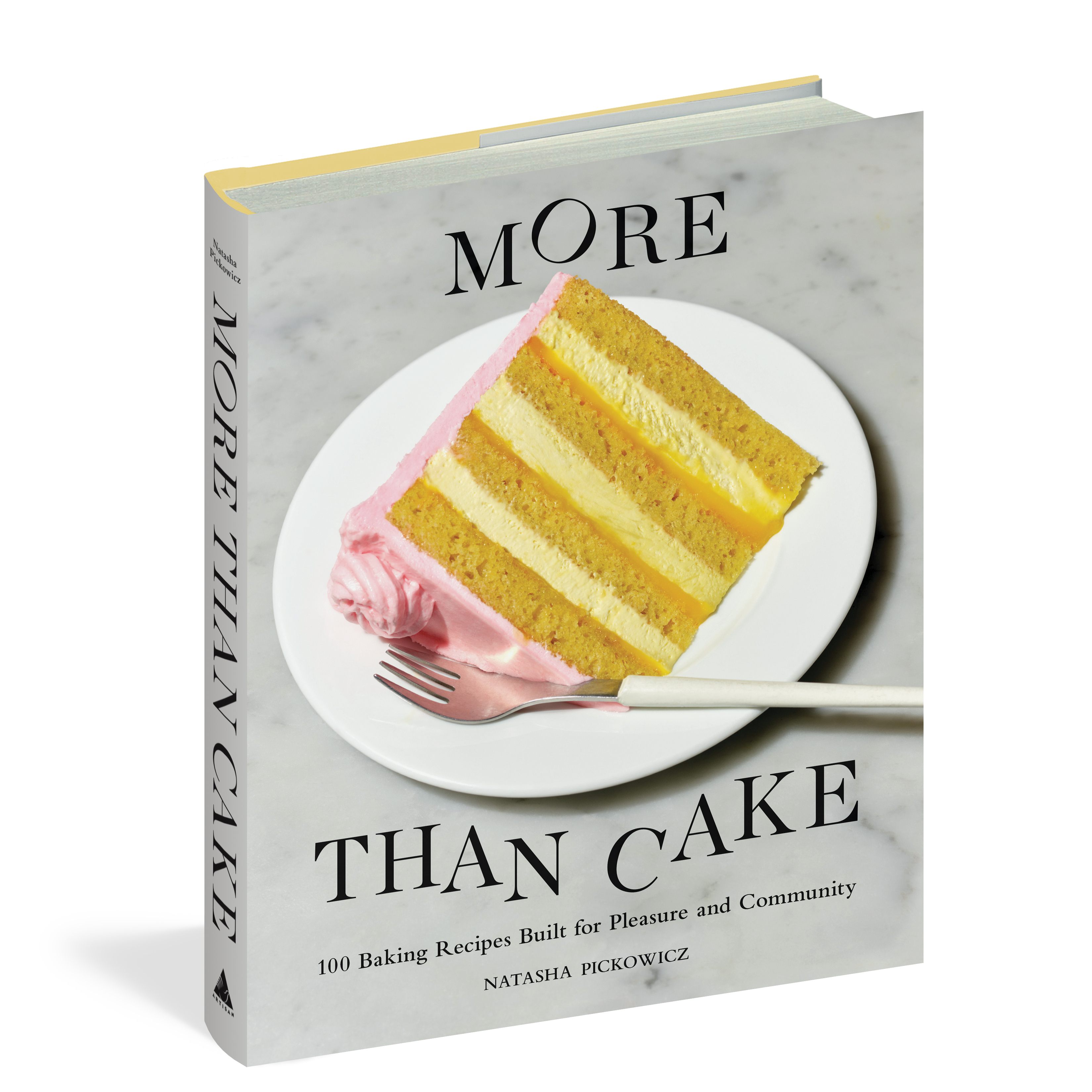

I spoke with Pickowicz about her upcoming book, More Than Cake: 100 Baking Recipes Built for Pleasure and Community, and the beauty of different baking traditions. Here is our conversation, which has been edited for length and clarity.

Q&A With Natasha Pickowicz

First of all, I just want to say congratulations on the book. Could you tell me a bit about it?

Thank you so much. Obviously it was an incredible amount of work, a total labor of love. I developed all the recipes. I styled every single photo. My mom illustrated the book. I feel like the images are so fun and personal because I shot them in the home I grew up in. And I feel like the recipes really work because I tested them in my little kitchen in Brooklyn instead of in a fancy restaurant with fancy tools.

What do you hope readers take away from this?

I’m hoping that my love of pastry and process and technique really speaks to people. I’m somebody who didn’t go to culinary school. I’m mostly self-taught.

I’m thinking about [baking] from a different perspective. I don’t know how to make a sugar rose, but I think that cakes with more natural decorations, like the plants around us, are actually a more beautiful aesthetic choice, to me.

At its heart, this book is really about why I’m baking and how closely it’s tied to my relationship with grassroots activism. It’s about how baking is a skill set a person can develop as a way of giving back to their community.

Your cake aesthetic is so distinctive. How did you start developing it?

When I first started working at Altro Paradiso in SoHo, I spent months and months developing my tiramisu recipe. The way that I make the tiramisu sort of is the whole basis for how I make layer cakes, which is not-too-thick cake layers that are evenly mixed and matched with creamy fillings. The cakes are saturated with another layer of flavor, similar to how a tiramisu is enhanced by a coffee soak. I’m thinking about building layers of flavor and moisture.

[In this book], you won’t really see American-style layer cakes, where maybe it’s a butter-based cake with three-inch-thick layers with a big separation of buttercream in between. Those are great things. That’s not what this is about.

I’m constantly reiterating this idea that these thinner cake layers that are super moist and have flavor built into them are all designed to be delicious on the palate. Pulling your fork through a slice of cake when you get those even, creamy cake layers is just one of the best sensations. I’m trying to design cakes that are not overly ambitious, but give you that sort of sense of satisfaction.

As someone used to working with very high-level professional bakers, what is your process like trying to translate some of that for home cooks?

I think that we have so much to learn as home bakers from how things get done in these sort of higher-production settings and the way that professional bakers work in restaurants—not just how organized your workspace is, but just the way that your work is built for replication and consistency.

It’s very reassuring to know that if you make this one thing, it will come out the same every single time. It’s up to you as the baker to decide if and when you want to make any changes along the way.

Your parents have lived in Hong Kong and Singapore, and you’ve spent significant time over there. Could you talk a little about your experience with bakeries throughout the Chinese diaspora?

I’m not a historian and not an expert on this, so I don’t want anything I say to be the definitive take on a really huge tradition of baking. But I think what I noticed when I would go to visit [my parents in Singapore] is that a lot of these pastry and baking traditions are partially a result of centuries of colonization.

You’re seeing Western techniques that are coming into East Asian countries. In places like Hong Kong, specifically, where there was British colonialist rule for so long, they’re bringing with them traditions of making shortcrust with butter or making eggy custards. And those things get remixed endlessly.

In Singapore, it’s not just Chinese influences and Western influences. There, you’re really seeing such a mash-up of this deep diversity. If you just go to a hawker market, you could have Malay food, Indian, Taiwanese, Cantonese—it goes on and on.

[Singapore] is really one of the craziest eating countries I’ve ever been to in my life. It’s so much fun being there. With baking specifically, I think a lot of those pastries that we think of when we think of Chinese bakeries are really like that because of that interplay with the colonialist influence.

Here in New York, I think what’s really interesting for me to see are how the children of immigrant parents are reinterpreting traditions—not just for an American palate, but it’s like this distinctly Gen-Z palate, too.

And there’s so many interesting ideas that get expressed by younger people who really see these traditions not as precious, but as a way to pay homage to culture by playing around with it or subverting it or reinterpreting it for your context in your situation.

Are there any particular spots in New York that stand out to you in this way?

Wenwen and Bonnie’s obviously are such hot spots here in New York right now, but I think it’s exactly for those reasons. I think that people are excited by the presentation of culture through this different, younger generation. It just feels so fresh and energizing.

I love Kopitiam, too. They do a great kaya toast, which is an example of that British colonialist presence [in Southeast Asia] and how they’re bringing together custard and milk bread, but in this totally different way.

How has this kind of cross-cultural hybridization influenced your work?

I did this pop up at Golden Diner [in Chinatown]. We worked on this super fun menu for the weekend after Thanksgiving. So I had my version of Thanksgiving pie, but it was with a red azuki bean filling. This is a texture or presentation that feels distinctly Western or American, but you taste it, and there’s Chinese five-spice powder, there’s condensed milk, there’s brown butter, and there’s red bean. It tastes like the inside of a red bean sesame ball.

That sounds delicious. Do you think we’re going to see more of these kinds of mash-ups in the future?

I think as it becomes easier to buy and get these kinds of ingredients outside of just a Chinese grocery store, whether it’s a specialty oil or a cool seed or spice, you’re going to see people playing around more with these ideas and making them their own.

And I think that’s really cool. I think that the most interesting thing about recipes and food culture is how these things change and adapt and how we’re discussing and sharing the stories and the context that makes that happen.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook