Rowdy ‘Mystery Hikes’ to Undisclosed Locations Were All the Rage in the ’30s

Tromping through strange woods in stockings and heels? Why not!

The quickest way to anger a traveler is to interfere with their plans; reroute, delay or cancel them. Deprive them of information, make them guess. But on March, 23, 1932, crowds descended upon Paddington Station, London after paying expressly for the privilege of being kept in the dark. They enthusiastically waited for a train with no known destination. Even the conductors had no idea where they would go. They were going to be passengers on London’s very first Hiker’s Mystery Train Express.

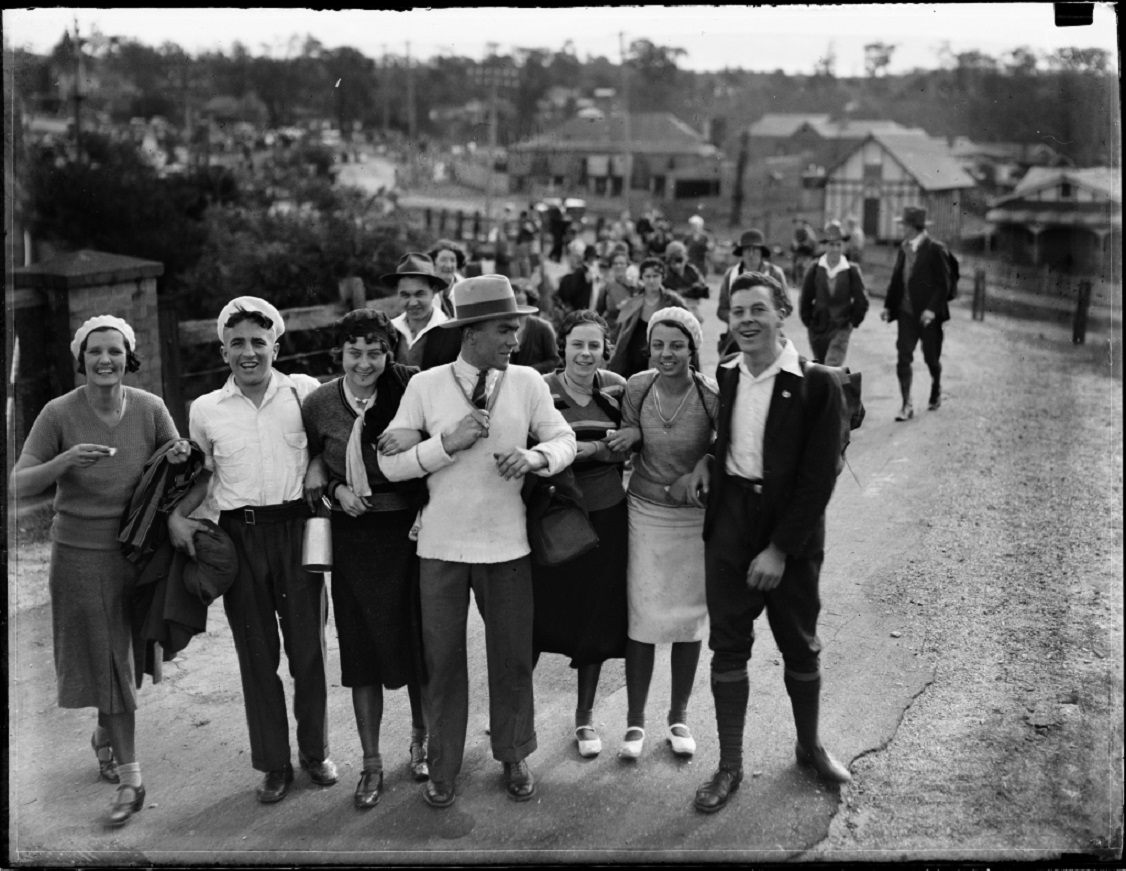

The train was a novel promotion dreamed up by the railroad that would transport hikers to a secret spot where they would then be set loose to tromp through the English countryside. The hikers looked anything but prepared for a wilderness excursion: the women wore long coats, skirts, stockings and heels. The men were more reasonably attired, as men’s fashions allowed, but they still had on shiny brogues and brimmed hats. A functional accessory that many carried was a walking cane; one grinning girl leaned out of the train as it left the station and waved hers triumphantly at a news photographer’s camera. The trip had whipped up such a frenzy of interest that several newspapers republished an account that described 1,000 “bare-legged, bareheaded” would-be hikers armed with knapsacks and walking sticks who had to be accommodated on a second “hastily provided” train, whose 14 carriages were packed to capacity.

The Hiker’s Mystery Train Express was not a one-time novelty. It was part of a craze for mystery hiking that swept the globe—particularly England, New Zealand and Australia—during the 1930s. “Rambling” gained popularity throughout the 19th century, and walking clubs and groups sprang up. In 1931 the Ramblers Association was founded to protect the rights of British walkers and advocate for open hiking spaces. Many people were also feeling the devastating effects of the Great Depression, and hiking provided free entertainment.

Mystery hikes were not free, of course, but they were relatively cheap. The cost of the trip from Paddington Station was 4 shillings. (There were 10 shillings in a half-pound note, the smallest denomination of paper money in England at that time.) The Paddington trip was typical of how a mystery train worked: passengers plunked down their money for a ticket and were then provided maps and information once they boarded the train. According to the promoters, even the train conductors did not know where they were going until they were presented with sealed instructions. Once the group arrived at their destination, they followed their maps along the prescribed route and were usually served a meal along the way. The Paddington passengers were eventually set loose to ramble through the verdant woods and fields of Oxfordshire and Berkshire.

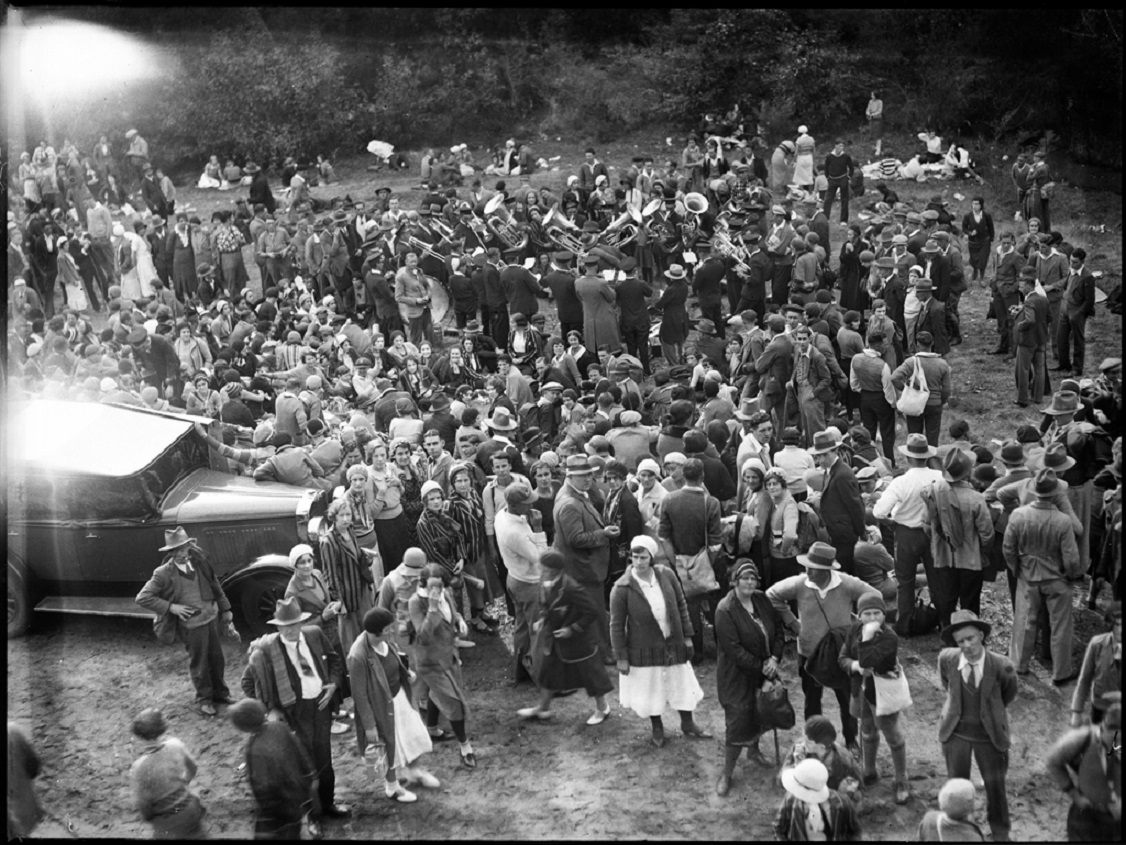

An account of mystery hiking in the May, 1937 issue of the New Zealand Railways Magazine reported that crowds about 700 strong patronized the country’s mystery hikes, circumnavigating routes around 10 miles long. In Australia, where mystery hikes were especially popular, thousands routinely swarmed the trains. In 1932 a crowd of over 8,000 flâneurs amassed for a mystery train departing Sydney.

In the United States, mystery hikes were more humble. They were largely a pastime of Boy Scout troops in the 1920s and ‘30s, offered as entertainment or a test of the boys’ wilderness prowess. Troops hiked locally rather than hopping on a train. Still, they were popular enough to be regularly covered in local newspapers. In December 1922, The Burlington Gazette delivered the tale of an Iowa troop who stumbled upon an unfortunate scene. “Their report states that the dog was frozen to the ground and they had to chop him loose,” read the account. “They buried him in a hole already dug, and one of the boys breathed a prayer for the canine soul.” Even more curious? The scout leaders who had mapped their route beforehand “noticed the dog and wondered if any scouts would bury it.”

Dead dogs aside, such excursions offered fresh air, exercise and affordable entertainment: what’s not to like? Well, plenty, according to critics. Mystery hiking was weirdly controversial.

First of all, mystery hikers received the same jibes as today’s “glampers”—people who partake in a glossy kind of outdoorsmanship that encompasses everything from renting out airstream trailers decorated in mid-century modern style to hiring teams to set up luxurious tents complete with cozy beds. In her book The Ways of the Bushwalker: On Foot in Australia author Melissa J. Harper writes that “serious bushmen … dismissed the hikes as senseless stunts.”

Mystery hikers were often labeled as rowdy; they smoked and drank. They were coddled on trips with tea service and lunches and entertained by live bands. They tore up the countryside and left a trail of trash in their wake. The real mystery, harrumphed an Australian newspaper article from 1933 was whether “it will ever be possible to take hundreds of people along without a trail of paper bags and banana skins from here to Halifax?” The New Zealand Railways Magazine gently mocked the hikers’ outfits: “Some seem to vie with each other as to who can wear the oldest clothes and still induce them to keep on; some wear collars and ties, shirts of various hues—and alas on a warm day, some have no shirts at all!” Motorists decried the ambulatory hordes they claimed blocked the roads.

Church leaders also frowned on mystery hiking. Hikes often took place on Sundays, and religious officials protested the events, believing they were tempting people away from worship. Baptist Reverend W.D. Jackson preached to his Melbourne church that railroads “baited” hikers with free tea and coffee and that they did so for “the sake of paltry profit and at the expense of the Sabbath”.

And finally, sexism reared its head. Many reports recorded the outfits of female hikers with alarm or bemusement; they were either dressed too appropriately for physical activity or not enough. Harper relays the words of the Catholic Archbishop of Brisbane who complained that “Men getting into women’s clothes is quite bad enough but the reverse is worse. I know that young girls dressed in men’s garments would go to places where they would never venture in their proper attire.”

Such gripes did not deter the crowds. Mystery hiking peaked in the 1930s, and never recovered from a decline prompted by World War II. Today, you can still go on mystery hikes organized by community groups and parks, but they are more akin to the scouting hikes of yesterday: meet at an appointed spot, get led on a surprising wander through the wilderness. And you can safely assume that attendance will be well under 8,000. But that doesn’t mean all mystery has been sucked out of travel. For those willing to put their plans in the hands of a stranger, companies like Magical Mystery and Pack Up + Go have only ramped things up a notch by offering mystery vacation packages complete with a flight.

Such a quest will certainly cost more than four shillings, but you probably won’t have to bury a frozen dog.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook