Mummified Baboons in Egypt Point to a Long Lost Land

New discoveries of ancient DNA could help scientists find the land of Punt.

In Ancient Egypt, people spoke of a land called Punt. It was supposedly a place of bounty, where you could get leopard skins, gold, or ostrich feathers. It was said pharaohs traveled there on ships and brought back live animals and even entire trees. But no one knows exactly where Punt was. Now, a mummified baboon may hold some hints.

“Since the beginning of the pharaonic era, we have records that talk about the trip to Punt and the trading activities between Egypt and Punt, all the way to 600 BC,” says Rawya Ismail, an Egyptologist who’s been in the field for more than 30 years.

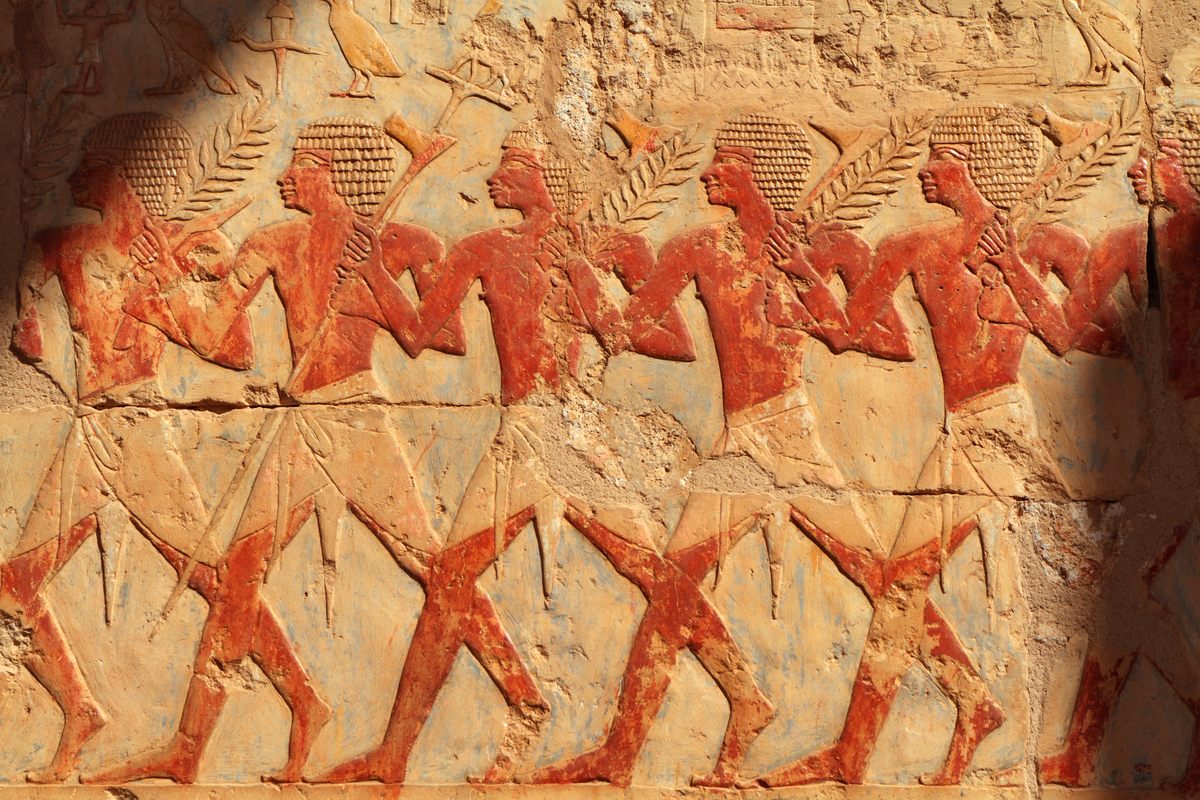

The first known mention of this land is believed to be on The Palermo Stone, one of seven fragments of black basalt possibly dating to 2925-2325 BC, inscribed with details of Egypt’s first five dynasties. It’s also been depicted in reliefs, including one at the Temple of Hatshepsut. But none of the records include an exact location.

Ismail and many Egyptologists suspect Punt may have been somewhere in the area from northeastern Sudan to Eritrea, Ethiopia, and northern Somalia. Hatshepsut and others described the journey to Punt as sailing south on the Red Sea. “But how far and where exactly?” Ismail says. “It’s not known for sure.”

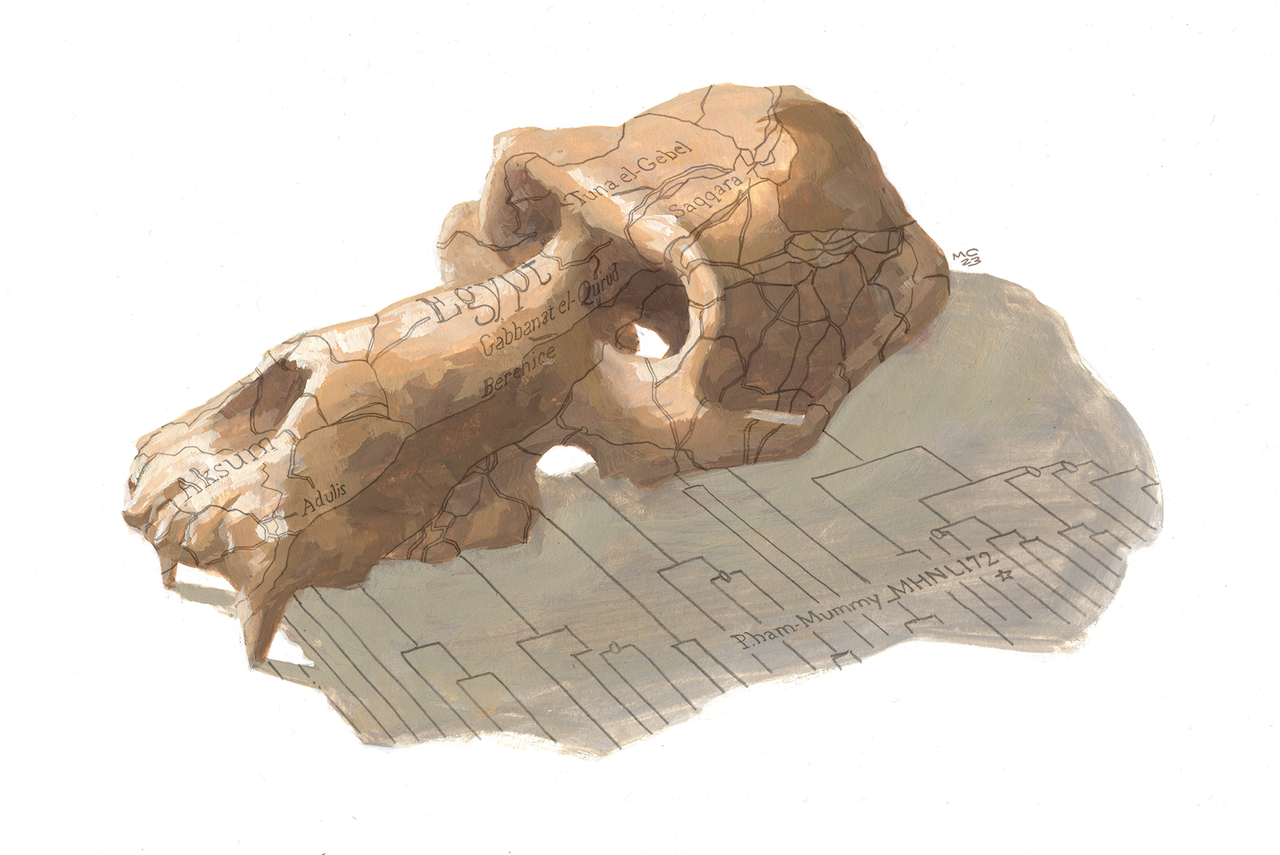

Now a specific possible location has emerged, thanks to a recent study of mummified baboon DNA by Gisela Kopp, Nathaniel Dominy, and their colleagues. They propose that Punt might have been where Adulis currently sits, an ancient port city on the Red Sea in present-day Eritrea. To understand the possible link, you need to understand the significance of baboons in ancient Egypt.

“Baboons are known as one of the two symbols of the god called Djehuty or Thoth,” Ismail says. “He was the god of wisdom, writing, knowing, and connected with the moon as well.” Ismail clarifies that Egyptians didn’t worship baboons or any other animals; they would notice creatures in the environment that exhibited characteristics of one of their gods and would therefore view it as a divine symbol of the god—not the god themselves. For this reason, a live animal or statue might be kept at a temple of the god or goddess it was linked to.

“In some cases,” Ismail says, “when the animal died, they’d mummify it and put it in a sacred burial spot.” Some were also mummified as votive offerings.

Records and reliefs indicate many live baboons were brought by ship from Punt to Egypt. A depiction in the Temple of Hatshepsut shows the primate cargo traveling with other goods believed to be from Punt.

Now, several millennia later, the DNA from the mummified baboons could indicate the baboons’ possible origins and therefore help target where Punt may have been. But accessing specimens and analyzing their DNA is a challenge, as Kopp, a primatologist, research fellow at the University of Konstanz, and the lead on the recent study, found when she first expressed interest more than a decade ago.

Paleogeneticists told Kopp it was impossible to get DNA from mummified baboons because mummification destroys all the DNA. This was a long-held belief that’s only changed in the past 10-15 years with the introduction of new DNA technology, says Albert Zink, the head of the Institute for Mummy Studies.

“We know that DNA degrades after death, and this strongly depends on environmental factors, such as heat and humidity,” Zink says. “People previously tried to calculate the possibility that DNA can survive in Egyptian mummies, and they concluded DNA wouldn’t be preserved due to Egypt’s high temperatures.”

Now, modern DNA sequencing technology (like Illumina, which was used in the Kopp et al study) allows researchers to distinguish ancient DNA from contaminants. “By applying this method, it’s been shown that there is DNA preserved in Egyptian mummies,” Zink says. “It’s not as well preserved as others, such as the Iceman, but it’s there and can be detected now.”

Mummification might have actually facilitated DNA preservation. “Because the mummification leads to a quick desiccation of the body, it can help DNA survive,” Zink says. Kopp et al noticed something similar in studying mummified baboon DNA. “DNA damage patterns didn’t look as severe as you might expect for a sample that old,” she says, attributing this potentially to the rapid dehydration during mummification. “This is something we need to explore more, because there haven’t been many studies on mummified animals.”

Some substances, such as bitumen and other oils used in mummification, can also interfere with DNA and hinder the analytical process. “We saw this in the royal mummies, especially in Tutankhamun, because they used a lot of bitumen,” Zink says. “It was hard to get any DNA—not because it wasn’t there, but because it was hampered by these substances.”

Kopp and her colleagues were able to extract and analyze baboon DNA from one mummified baboon specimen unearthed at Egypt’s Gabbanat el-Qurud in 1905 and kept in France’s Musée des Confluences. They found it most closely related to the modern populations of P. hamadryas in Eritrea, Ethiopia, and eastern Sudan. In other words, if there were an Ancestry.com test for mummified baboons, it might reveal this baboon was most likely a match for the region many believe Punt was in. “Those [human ancestry analyses] look at a different part of the genome, but it’s the same approach. You look at the genetic variation you have and try to find the population closest to it,” Kopp says.

Based on where they were found and the timeframe to which they were dated, combined with the DNA analysis, Kopp says the baboons “should’ve been imported from Punt. And from the location, they coincide with Adulis.”

Kopp and her team know this study doesn’t confirm Punt’s location; it presents one possibility. “We need to replicate the study with more samples to see if the location that we identified applies,” she says. “This was only one sample, and it’s one of the first studies that successfully analyzes ancient DNA from a non-human primate.”

The study also unexpectedly developed a side project. The team discovered one of the mummies, which was believed to be a primate for many years, was actually a falcon and spiny mouse. “At first we thought maybe the falcon had eaten a mouse before they mummified it,” Kopp says. “But they might have intentionally put them together because the night equivalent of the god represented by a falcon is a shrew.”

Maybe the mislabeling was just the result of a priest eager to make some money. “Mummifying baboons and selling them as votive offerings to the pilgrims was a source of income for priests,” Ismail says. “Sometimes X-rays show there were no baboons inside the mummy—just a piece of bone or stone or something. The deceived pilgrim would buy it assuming it was a baboon mummy.”

We may never know how the falcon and mouse ended up mummified together and mistaken (or maybe deliberately misrepresented) as a primate. But they’re a reminder that, in trying to connect the dots of the ancient world, even things we think we know can be full of surprises. “There’s always something new,” Ismail says. “In this field, you’ll never stop learning.”

For now, all three experts agree that further pinpointing the exact location of Punt requires more data and archeological evidence.

Kopp believes that will only be achieved through collaboration. “It was the interdisciplinary nature of this project—connecting biological expertise with my collaborators who have backgrounds in anthropology and Egyptology—that made this study work. One discipline wouldn’t have been able to reveal this full story.”

Perhaps it’s no coincidence that the baboon, one of the symbols of Thoth—the god of wisdom, time, and writing, who was known to suggest problems could be resolved by assembling a group—is at the heart of this step that’s bringing us closer to solving the mystery.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook