Discovering the Unexpected Wonder of Mumbai’s Coastal Wildlife

Photographer Sarang Naik is reintroducing his hometown to its rich biodiversity, from glowing corals to dazzling sea slugs.

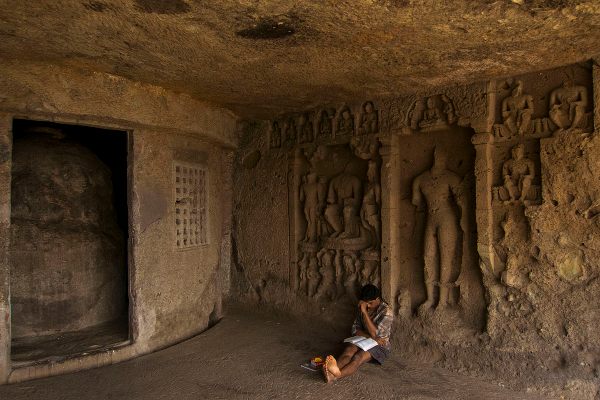

Bright pink flamingos saunter through shallows, some pausing to nibble algae and tiny invertebrates near the surface. The birds’ movement creates small ripples in the reflection of mustard-yellow apartment buildings rising behind them. In another image, shot at night, bioluminescent soft corals glow an otherworldly blue in the shadow of an urban skyline. For Mumbai-born photographer Sarang Naik, these shots capture “life just quietly going along” in and around a city of 20 million.

Naik’s surprising, wondrous images of terrestrial wildlife have earned him accolades—a dynamic shot of a mushroom shedding spores won the Art of Nature category in this year’s prestigious BigPicture competition. But his favorite subjects are found on Mumbai’s shores. During optimal low tides that occur just once or twice a month, small tidal pools dot the coast, ringed by sediment and slippery rock. There, elaborately patterned sea slugs share space with spotted moray eels and tubular zoanthids, or soft corals. As a member of Marine Life of Mumbai, a volunteer-run collective, Naik has helped document dozens of species in this intertidal zone. He and his colleagues hope to highlight both the city’s rich coastal biodiversity and the desperate race to protect it from development.

Atlas Obscura spoke with Naik about what draws him to the urban coast, how it continues to delight him, and the heartbreak of losing some areas forever.

How did you become a wildlife photographer?

I was always interested in wildlife, wildlife research, and conservation studies. That was always the plan, to get into those fields. In college, photography started to happen. I started documenting the wildlife that I had been observing and I realized I was more invested in that artistic side of me than the scientific, though they both feature in the end. I completed my bachelors in zoology and the plan was to get into a masters program, but I just went into doing photography full time. Also, I’m a very restless person. I like to move around. Photography helped me connect with that side of me, constantly exploring new places, finding new things.

How did you get involved in Marine Life of Mumbai?

I was not an original member, but one of the people who started it was my friend and college classmate, Abhishek Jamalabad. We used to go out on nature trails for birdwatching. Through him I started going out on the shores of Mumbai. Nobody knew that there are octopuses found around Mumbai. I mean, the people that look for them, the scientists and the fishermen, they knew. But the general public had no idea. So, to create awareness and also to document the wildlife, they started the collective. The main thing is to document as much as we can, upload it to iNaturalist and other [citizen science] sites, and encourage people to come to the shores and see for themselves this beautiful nature we have, right in the city.

During the group’s educational shore walks, how do first-timers react?

People can’t believe that you can see these things in Mumbai. The same is true even for us, the people who have been exploring the terrestrial wildlife in Mumbai since a very young age. We had that mindset that, to see wildlife around Mumbai, we had to go into the forest, that there’s nothing on the shore, it’s just dirt and garbage and pollution. Honestly, the shores are quite polluted, and there’s a lot of garbage. But despite that, there is incredible biodiversity. So the first response is disbelief. The second is excitement. Adults become like children when they first see an octopus or sea anemone.

Mumbai is like a character in your work.

There are two cities. When you land in Mumbai and travel around, there’s that one city, the in-your-face city, which is extremely crowded, busy. And you go to the shore and feel it’s dirty and polluted. And yes, that’s true. But at the same time, as you slow down and take your time to explore the city—not just the wildlife, but everything else—you start really seeing the laid-back aspects of the city, where life is just quietly going along. And I think that is really beautiful.

I’m mainly shooting for the citizens of Mumbai, who have the idea that there’s no wildlife here. The animals are the original citizens of the city. They say, “I also belong here and we can coexist together.”

What are some of your favorite animals in these intertidal zones?

The bioluminescent soft corals, Palythoa mutuki. They are found in a few patches in Mumbai and, like a lot of corals, they glow when you shine a UV light on them at night. The first time it happened, it completely blew my mind. And it is right there, not in some protected area or hard to access. It’s right there, in the city.

Another thing that really excites me is the sea slugs. Honestly, until about four or five years ago, if you had told me there were sea slugs in Mumbai, I would have laughed at you. That’s how completely unaware we were. A few researchers had kind of studied them back in the 90s, but then they stopped. There was no data, there was no info. On a shore walk, one person saw a sea slug, and another person saw a sea slug, and then everybody started seeing sea slugs everywhere. In four years we have documented more than 40 species in Mumbai. It’s quite crazy, to be honest.

They are some of my favorite animals because they are so vibrant, and they have these weird adaptations. They have stinging cells that they use for self-defense, and they steal chloroplasts from algae and store them in their body and use them to make their own food, a lot of crazy stuff like this. To actually be able to observe them, in my home city, is amazing.

What do people in Mumbai need to know about their city’s rich coastal biodiversity?

Sadly, we are losing the shores to reclamation. There’s one particular project going on, building a road along the coastline of Mumbai, and we’ve lost quite a few very beautiful shores to it. And that is permanently lost now. So that is something that really hurts, especially after you have explored it and seen the biodiversity. One of the reasons we keep trying to raise awareness is to put public pressure on the authorities to protect these shores, to see them as rich areas of biodiversity and actively preserve them.

What’s next for you?

I want to explore other cities in India, because it’s the same story everywhere. There is a lot of wildlife everywhere, but people don’t observe it. They don’t pay attention. And when somebody pays attention and finds something, suddenly everyone starts seeing it, right in front of them. That’s what happened in Mumbai, and I’m sure the same thing will happen wherever I go. There are so many people in India, in Indian cities. Despite that, there is so much wildlife. It boggles the mind that we can live together, in the same place.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook