Morbid Monday: The Death of Chang and Eng, Conjoined Twins Until the Last

Chang and Eng’s death cast in the Mütter Museum (photograph by James G. Mundie)

“They were exhibiting themselves with two of their sons. The fathers were beginning to show marks of age, Eng especially, who looked five years older than his brother.”

Dated from 1874, this account from the Daily Record draws a sorrowful portrait of Chang and Eng, the once glorious conjoined twins from Siam (now Thailand) who enjoyed in their heydays an international popularity as human wonders on both side of the Atlantic. Married to two (unjoined) sisters in 1843, they took the last name of Bunker, quit the entertainment business to settle down with their wives in rustic North Carolina, and became successful farmers, far removed from the freak shows.

Portrait of Chang and Eng in 1830 by Irvine (in the collection of The Hunterian Museum / Royal College of Surgeons of London)

It was almost happy ever after. But soon after the Civil War broke out the twins’ fate got a bit more complex. The loss of two daughters of the 21 children the two brothers had between them also heightened Chang’s alcoholism. (Eng never drank and, as physicians noted, never shared any alcohol effects when Chang dived into his tipsiness bliss.) Moreover, the “Lifetime Duet” also lost a fortune in loans they took in the Confederate currency. Ruined and bitter at 54-years-old, Chang and Eng had no other option but to go back on the road as anatomical curiosities.

(via Our State / North Carolina)

Unfortunately, their comeback attempt caused a myriad of problems. Their exoticism had faded; Chang and Eng were no longer novelties. To attract an audience, they had the idea to bring with them two of their very normal children on their journey as part of the exhibition. It worked for a while, but the audience found the brothers pretty damaged and physically diminished. After a couple of years touring the United States, their sight started to decline, as did their health. Chang was partially deaf and weakened by his alcoholism.

In 1868, the Siamese Twins accepted P.T. Barnum’s proposal to travel through Europe, and on Barnum’s request (mostly for promotional purposes), consulted with the best physicians to be examined, with one burning question: Could they be surgically separated?

(via Lost Museum)

In the past, Chang and Eng categorically refused to think about such a medical intervention. The subject was sensitive, almost taboo, and in 1836 an angry Chang allegedly tried to kick Philadelphian doctor Thomas Harris who suggested he could practice the possibly lethal surgery. At the time Chang and Eng had no need nor desire to be removed from each other. Their very peculiar physique was never a handicap and even connected by the sternum, the twins were independent men. But it became clear for the pair that two linked bodies aging at differing rhythms would be an exhausting problem.

In the last years of their life, with the knowledge that it might reach an end soon, the two became almost obsessed by the idea of a possible separation, dreading the moment when one would have to carry on with his brother’s corpse at his side. Tied up for life, Chang and Eng desired their own deaths. Separately. Sadly, the physician’s answers carried no hopes, as they all advised against severing their cartilaginous link. The procedure would likely result in a tremendous loss of blood and kill them both.

Upon their return to the United States, the situation was almost impossible. Chang had a fit which left him paralyzed and obliged Eng to prop his legs with straps and crutches in order to activate his brother’s legs like a puppeteer. Back in their village, both hopeless and frustrated, Chang and Eng kept having arguments with each other and begged Dr. Hollingsworths, the local physician, to split them apart. Yet a few months after, the same doctor was called down to their house to certify their deaths. On January 17, 1874, Chang left our world first, then Eng did too, three hours later, asking as a last favor that the dead body of his brother be pulled closer to him.

Illustration from the “Report of an autopsy on the bodies of Chang and Eng Bunker, commonly known as the Siamese twins”, 1875. (via Internet Archive)

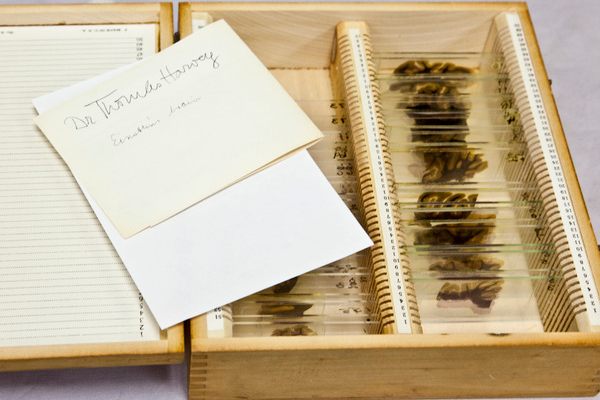

The lives of our twins ended in a dolorous way, but our story isn’t finished. Once Chang and Eng gave up the ghost, physicians rushed on the remains. The bodies were sent to the College of Physicians of Philadelphia to be dissected, studied, and photographed. Eventually, the autopsy of their mysterious organic bridge revealed that part of their livers was connected. Whenever a separation might have occurred, there was no chance that they would have survived it. After the exam, the bodies were cast facing each other, and are now on display, as are their livers, in the Mütter Museum in Philadelphia. Livid and ghostly, this cast exists as much as a virtual memorial as a medical model for the two legendary figures that were Chang and Eng, the original Siamese Twins.

Chang and Eng’s death cast in the Mütter Museum (photograph by James G. Mundie)

Footnote: Chang and Eng were never much known in their birthplace of Thailand, until very recently, in the 2000s, when Thai director Ekachai Uekrongtham produced a musical based on their biography. Since then, a memorial statue has been erected in Samut Songkhram, their hometown.

DEATH CAST OF CHENG AND ENG: MUTTER MUSEUM, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Morbid Mondays highlight macabre stories from around the world and through time, indulging in our morbid curiosity for stories from history’s darkest corners. Read more Morbid Mondays>

Join us on Twitter and follow our #morbidmonday hashtag, for new odd and macabre themes: Atlas Obscura on Twitter

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook