A Poet’s Guide to the Moon and Eclipse

Author Christopher Cokinos can’t get enough of the moon.

In 2017, English professor, poet, and author Christopher Cokinos embarked on a road trip with a fellow poet into the depths of Idaho. The pair found what they were looking for—a small plot of land with a fabulous view of the sky, nestled in the Little Lost River Valley. A few days before the total solar eclipse, Cokinos returned to set up camp. The eclipse he and his friends witnessed was so incredible that it took him two and a half years to craft a poem about it.

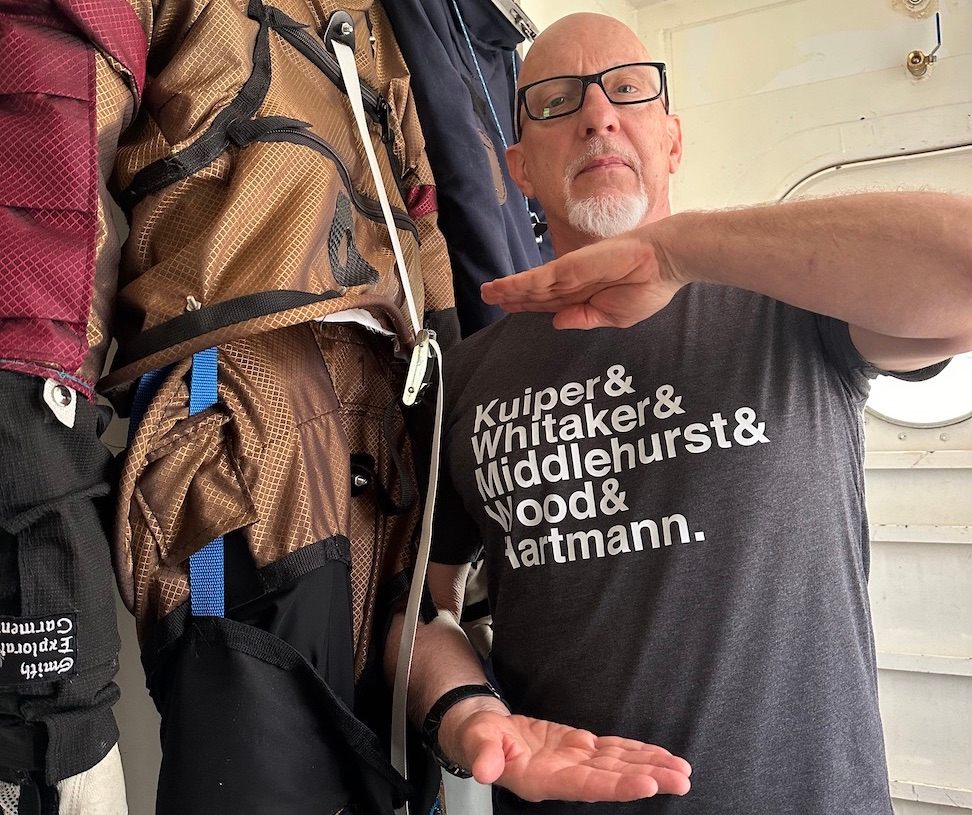

Cokinos’ love of the moon (he’s especially fond of the Lunar Apennines and the Aristarchus Plateau) has manifested into his latest book: Still As Bright: An Illuminating History of the Moon, from Antiquity to Tomorrow. He also just completed a simulated lunar mission at the University of Arizona’s Space Analog for the Moon and Mars—during which he wore a t-shirt that read, “Kuiper & Whitaker & Middlehurt & Wood & Hartmann,” an homage to his lunar science heroes.

A few days after he returned from the simulated mission, Cokinos spoke to Atlas Obscura about the moon’s sublime landscapes, the ethics of space exploration, and the Apollo 15 astronauts’ deep connection with the moon.

What prompted you to write about the moon?

It was a confluence of looking for a project that was a nonfiction mix of memoir and research, which I’ve somehow stumbled into specializing, and, as I write in the book, pulling out my telescope for the first time in a while.

For all these years—despite being a child of Apollo [missions]—I’d never really looked at the moon with any kind of attention or care. So one night, I did, and it really swept me up. It was so stunning. I recognized the moon as a sublime landscape.

The moon has this important cross-cultural function: spirituality, religion, timekeeping, and so forth. One knows that intellectually. But then to really deep dive into that, that became very gratifying.

You just returned from Imagination 1, an all-artist simulated moon mission. How does space exploration stand to benefit from perspectives outside scientific disciplines?

Well, we take culture with us. Astronauts already do! But what has not happened is a concerted effort to bridge C.P. Snow’s “Two Cultures” divide. The arts provide a fresh, descriptive, and metaphorical way to convey the moon.

How are we talking about the moon? The reason why we have this revival of lunar exploration is because we discovered water ice. Okay, so, how do we talk about that? Are these resources to exploit? Are they gifts to cherish? Are we going to colonize the moon? Is it a frontier? Is it a heartland? Description is crucial.

And the role of the arts is not simply propagandistic. I’m a fan of space exploration. I believe that making our species multi-planetary is a good thing…if we are able to make every place that we live vibrant, just, and sustainable. And the arts are part of that.

You spent much of your career teaching at the University of Arizona and living in Utah. How has the American West impacted your relationship with the sky?

I feel like I’m on a planet when I’m in the American West. This is a world that is deep in time. You can see the layers, especially in Utah, of geologic time.

And Tucson has—because of the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory—this unique point in history in terms of lunar exploration, astronomy, environmental sciences, and the confluence of those [sciences] with the arts. There’s a great energy here. Biosphere 2 is another place where that happens, where the arts and science come together.

Do you have a favorite story about the moon?

I write in the book about Apollo 8 and Apollo 15, and the differences between how they describe the moon.

For the first time, human beings leave Earth and have these profoundly interesting experiences. But the descriptions are largely pejorative; [Apollo 8 astronauts] were not trained to look at the moon carefully. But Apollo 15 [astronauts] essentially have master’s degrees in geology. On one hand, they have enthusiastic [reactions]: “Wow, it’s beautiful.” “It’s spectacular.” And, on the other hand, they have these very precise geologic descriptions.

[Apollo 15 astronauts] look at the moon as a kind of home. It’s this place utterly sublime and different. They had spent so much time preparing and thinking about the moon, that they had an ability to connect to it on its own terms.

How do you plan to experience the April 2024 eclipse?

I’m going to go home, back to Indianapolis. My wife and I will be with my sister and her friends, up on the rooftop of her downtown apartment building. It’s the antithesis of being in the middle of Idaho.

I’m imagining that I will hear the roar of tens of thousands of people. Our small group of twelve [at the last eclipse] put up quite a lot of whooping and hollering—so I think we’ll probably experience a much larger, urban version of that.

When readers experience the April eclipse, what do you want them to think about?

Just to experience it, and to experience the sun. But then, also, to think about the moon—as our very lucky companion.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook