The Medieval Thieves Who Used Cats, Apes, and Tortoises as Accomplices

The Banū Sāsān were known for turning animals to lives of crime.

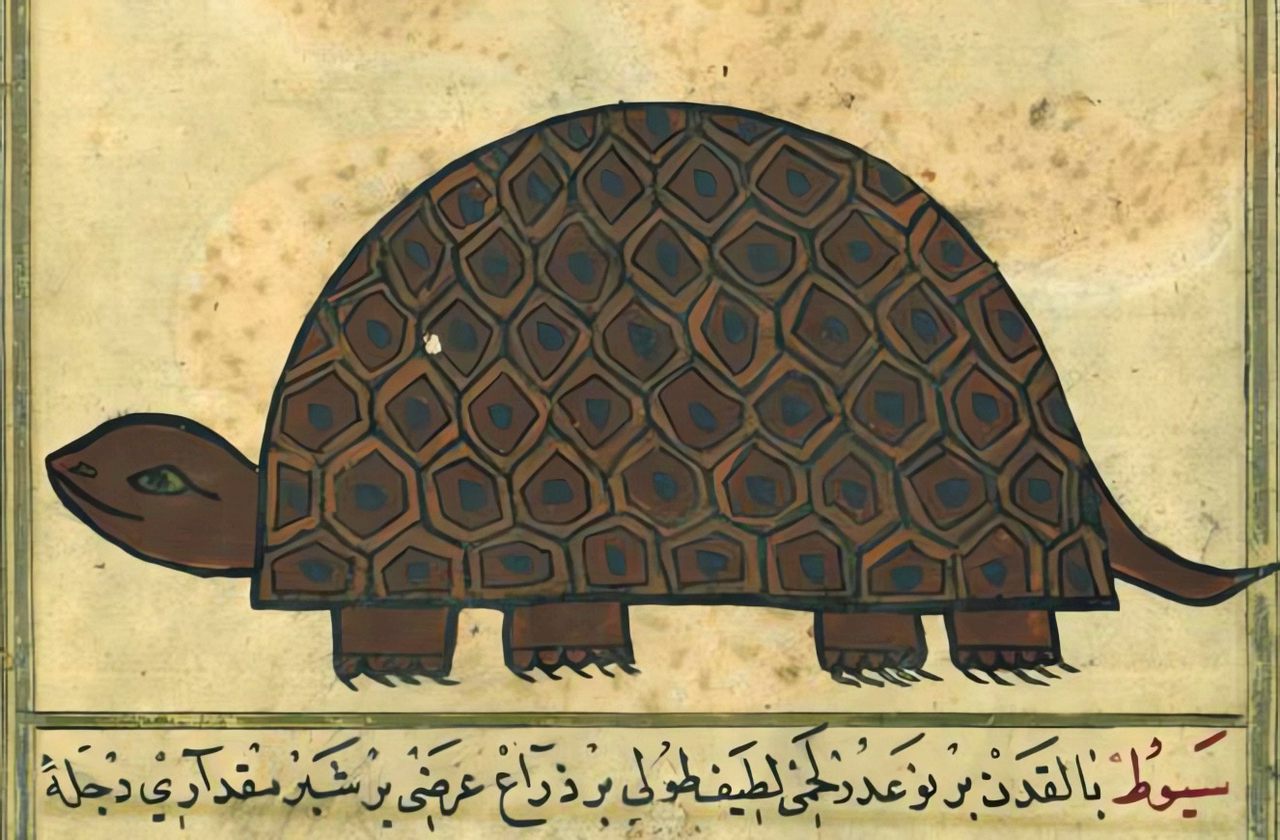

No one gets as creative as a burglar on a mission to rob without getting caught. Newspapers and televisions are an archive of interesting techniques employed by the genius-yet-criminal minds of thieves. Reaching back even further, burglars in 12th-century Persia found an unlikely accomplice in the form of a tortoise. The four-legged reptile had rather one of the most important tasks in the robbery—giving the green light to commence the theft.

For these lawless masterminds, a group known as the Banū Sāsān, the tortoise played a crucial role. Once the doors of the targeted home were forcibly opened, a tortoise with a candle on its back was the first to enter the house.

“The burglar has with him a flint-stone and a candle about as big as a little finger. He lights the candle and sticks it on the tortoise’s back,” writes Clifford Edmund Bosworth, an English historian in his book The Mediaeval Islamic Underworld: The Banū Sāsān in Arabic Society and Literature. “The tortoise is then introduced through the breach into the house, and it crawls slowly round, thereby illuminating the house and its contents.”

The tortoise also helped by frightening anyone in the house. A scream would alert the thieves to abort their mission.

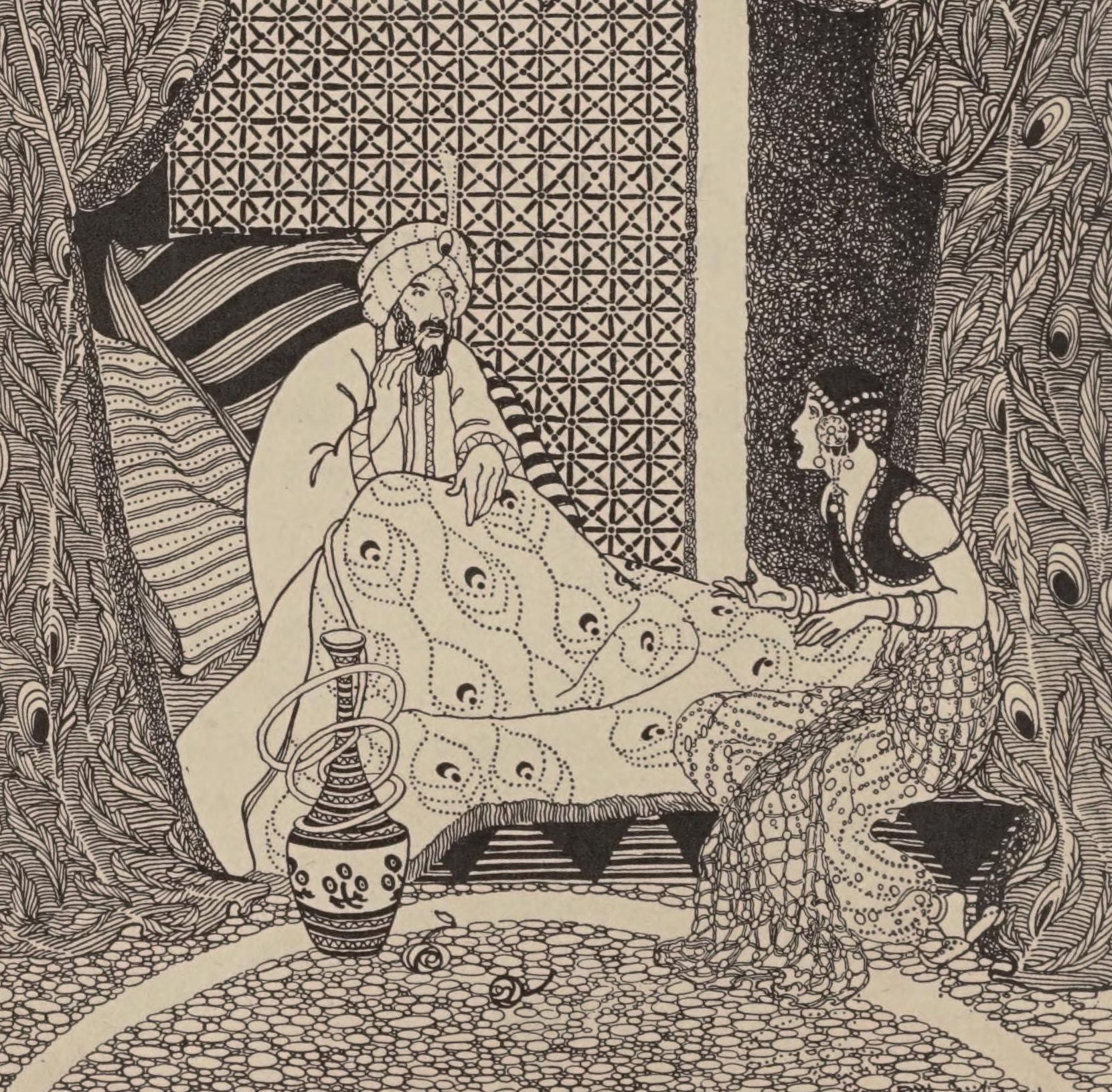

The Banū Sāsān didn’t just train tortoises to assist them; other animals joined the gang, including at least one ape which was trained to make a gesture of salaam— the Muslim act of piety—and pray and weep like a human. The famous medieval Syrian Arab author and scholar Jamāl al-Dīn ʿAbd al-Raḥīm al-Jawbarī witnessed such an ape, dressed in the most luxurious clothes, arriving at a mosque for Friday prayers on a mule with a saddle decorated in gold. Following the ape were three Indian slaves that made preparations for his Friday prayers. Al-Jawbari writes in his book, Kitāb al-Mukhtār fī kashf al-asrār or The Book of Charlatans, “The ape now removed its clothes, pulled its handkerchief out of its cummerbund, and placed it in front of him. It rubbed its teeth with the stick and performed two prostrations of thanks for ablution and two of greeting to the mosque. Then it took the prayer beads and busied itself telling them.”

According to the ape’s trainers, the creature was actually a human, a prince who was under a spell cast by his wife to change his appearance. The wife suspected the prince to be in love with one of his slave boys and overcome with jealousy had thus cast the spell. To be restored to his human self, the prince was required to pay 100,000 gold pieces, but was short 10,000. The trainer then turned towards his audience asking them for help. Within no time, the trainer thus, collected a modest sum.

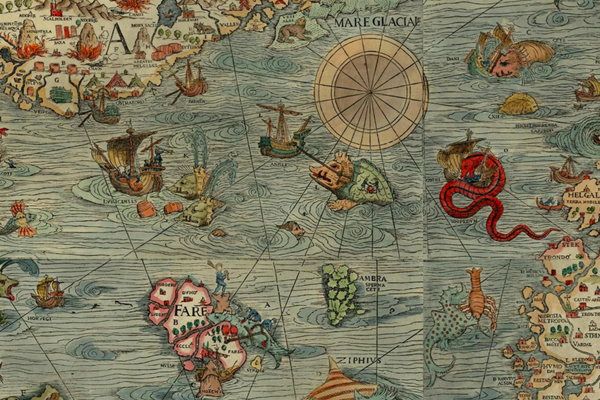

Today, the term “Banū Sāsān” has come to simply mean “beggar” in Persian, but according to Al-Jawbarī any person that practiced “deceit and trickery” was to be considered a member of the rogue tribe. For most, the life of trickery and violence was a conscious choice. The members of the tribe were bound together neither by religion nor by blood, rather by their collective rejection of the norms and values of the society.

“The origins of the Banū Sāsān tribe are hard to pinpoint, as this seems to have been a conglomeration of many different ethnic groups and language groups,” says Kristina L. Richardson, a historian of medieval Middle East at the University of Virginia and the author of Roma in the Medieval Islamic World. “Perhaps the most important aspect of the Banū Sāsān is their rejection of the values of settled society,” Richardson explains.

The subtribes of the thieves were formed according to the methods of burglary employed by them; the tricks of the Banū Sāsān were often passed down through generations. While the “tunneling” thieves (ashab an-nugib wa-l-Qatari) worked their way into the houses by breaking through walls, the “smash and grab” thieves (al-lusis al-hajjamin) simply raided easier-to-access houses, stealing whatever was desired and found. Bosworth points out that besides tortoise, the Persian burglars also worked with pigeons and cats to confirm that the target house was empty to rob.

As fantastical as these thieving animals may seem may sound, you may have heard of it all before in the famous tale of Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp, where the pet monkey, Abu, is trained to trick people and assist Aladdin in robbing people of their food, cash or other valuables.

Looking back, it is possible that the character of Abu is not a creation of pure imagination, but instead one inspired from the four-legged accomplices of the medieval Persian rogue group,

“The lifestyle of the Banū Sāsān inspired a number of medieval writers to center them in poetry, picaresque tales, shadow plays, and in One Thousand and One Nights,” Richardson says.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook