How Kosher Wine Became a Hit in the Caribbean and Beyond

Manischewitz has a historic consumer base not only in the Caribbean, but also in African-American and East Asian communities.

Growing up on the Dutch Caribbean island of Curaçao, 34-year-old Diahann Alexandra Maria Atacho’s parents would regularly turn to an unexpected beverage when they wanted something “special to drink.” They’d pull a bottle of Manischewitz—a brand of incredibly sweet wine well-known to American Jews—and serve it in a crystal wine glass, filled to the brim. “Because they grew up very poor, with occasional food scarcity, they were both quite hesitant to throw out food-related stuff. So every time we drank the wine, we’d need to make sure it hadn’t turned into vinegar,” Atacho recalled in an email. “We never finished a bottle and saved it for the next time, but sometimes it sat too long in the fridge.”

Atacho’s family is not alone. Manischewitz has a consumer base not only in the Caribbean, but also in African-American and East Asian communities. Of the over 900,000 cases produced in 2015, some 200,000 were exported, largely to the Caribbean, Latin America, and South Korea. What is most surprising is this is not a new trend. Since Manischewitz came on the market in the 1930s, it has found devotees beyond the American Jewish community, who often serve the kosher beverage for holidays like Passover. While Manischewitz has cemented its cultural status as a part of American Jewish identity, the brand has also made its broad appeal a central part of its marketing strategy, bridging gaps across racial, religious, and cultural barriers.

The reason for the beverage’s sweet—some might say sickly—taste is due to the grapes used to make it. By the 20th century, immigrant Jews were producing kosher wine from cheap, hardy, and sour Concord grapes from the American Northeast. Adding significant amounts of sugar made it drinkable. During Prohibition, some of these winemakers received special dispensation from the government to continue making wine out of this domestic crop for religious purposes, and were consequently prepared to respond to an expanding market when alcohol became legal again in 1933.

But this domestic Jewish wine wasn’t sold as Manischewitz until after Prohibition. The B. Manischewitz Company, LLC was founded in 1888 by Rabbi Dov Behr Manischewitz, who was a pioneer in making kosher matzah and then other products like gefilte fish and soup on an industrial scale. In the 1930s, Meyer Robinson, co-owner of the Monarch Wine Company, proposed selling his vintage under a licensing agreement with the well-established Manischewitz name for a promotional boost. When Manischewitz-branded wine hit the market around 1935, it quickly became a staple in many Jewish-American homes.

For American Jews, it’s a beverage long loved more for its nostalgic value than for its taste. Case in point, in an episode of The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel, the titular character tells a non-Jewish acquaintance that “Manischewitz is best enjoyed in small quantities.” University of Delaware history professor Roger Horowitz, author of Kosher USA: How Coke Became Kosher and Other Tales of Modern Food, remembers his family using Manischewitz in charoset, a dish of fruits and nuts eaten at Passover that represents the mortar used by the Jews in Ancient Egypt. He recalls the frustration of his wine-connoisseur father that Manischewitz was, at the time, the only kosher option.

Until he started researching his book, Horowitz had no clue about its popularity in non-Jewish communities. He refers to it as the United States’s “first crossover kosher product.” He found one of the earliest mentions of this phenomenon in a 1954 article in the Jewish magazine Commentary, where the author pondered why African-American journalists were present at an event for the Monarch Wine Company in Brooklyn. He didn’t pursue a tip from an unnamed African-American reporter, who told him that Manischewitz is “like the wine their mothers and grandmothers used to make down South.”

As Horowitz writes, this was an “astute insight”: Many Southern African-American communities had long made wine out of Scuppernong grapes, which shared both the Concord grape’s durability against temperamental weather and their acidity. According to Wine Enthusiast, Muscadine (which Scuppernong grapes are a variety of) wine was a source of medicine and food for enslaved people, and later a source of income for Black farmers.

Horowitz argues that the Great Migration to northern cities may have exposed African Americans to Manischewitz, which became known as “Mani.” Blacks and Jews often lived in close proximity, excluded from White, Christian areas. Its slogan, “Wine like mother used to make,” might have hit close to home for both communities. But the crossover wasn’t without market influences. Realizing that there was a relatively small number of Jewish consumers, Monarch knew it had to look elsewhere for customers if it wanted to keep growing.

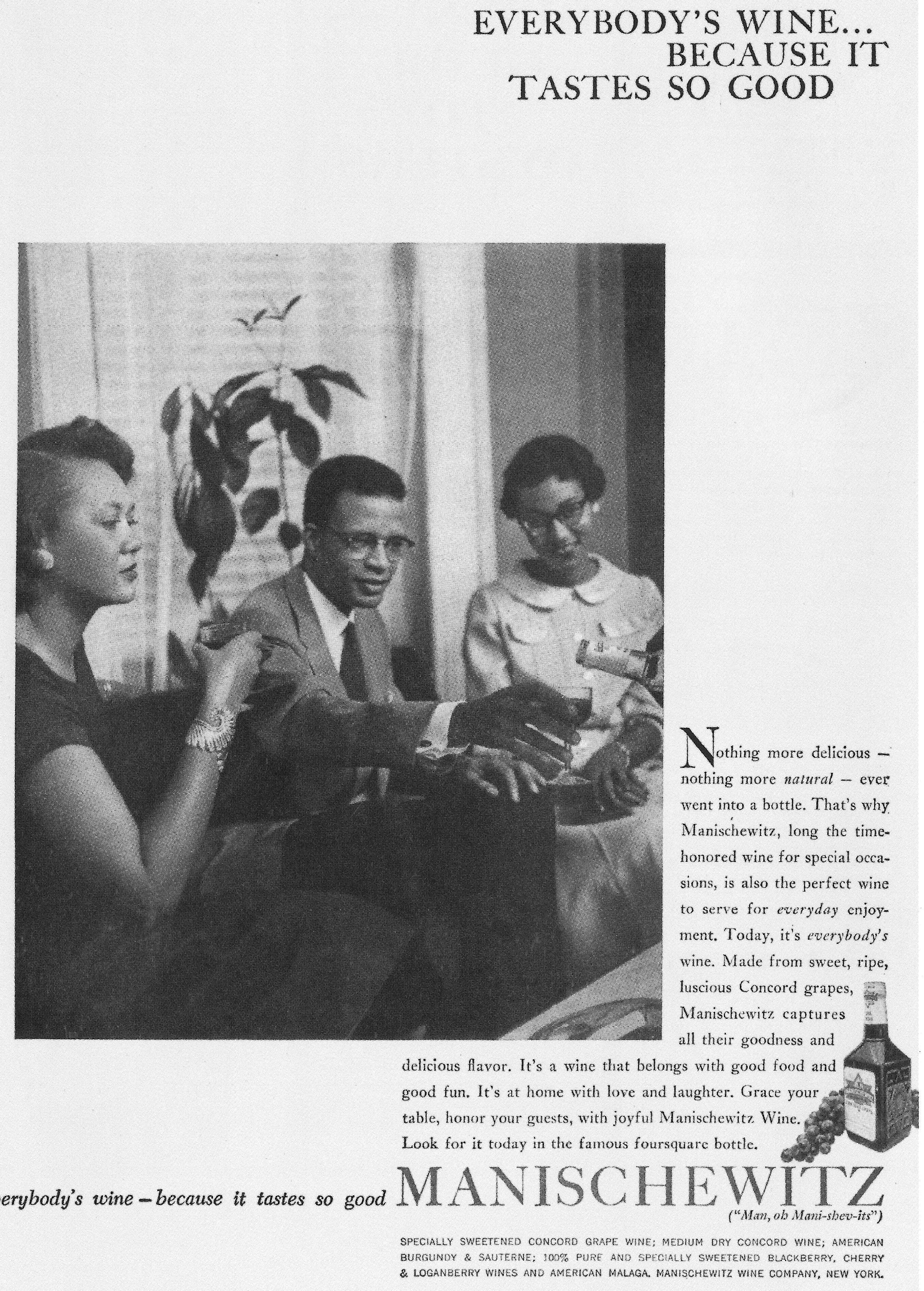

The company launched a multi-million dollar advertising campaign in the 1950s that expanded across media, notably with ads in magazines, radio spots (including competitions with disk jockeys vying for who could best pronounce the name) and even a billboard in Times Square. The product was also embodied in company president Meyer Robinson, who would schmooze at New York hot spots like the Copacabana and the Latin Quarter, particularly becoming friends with baseball legend Jackie Robinson of the Brooklyn Dodgers.

“Mr. Manischewitz,” as his daughter jokingly called him, even got Jackie Robinson into his Long Island country club, one of the few at the time that would admit Jews and African Americans. It was this sense of solidarity in the face of discrimination, Horowitz says, that built business relations between the two communities, such as the Jewish-run Chess Records, which produced the likes of Chuck Berry, Bo Diddley, and Muddy Waters.

Most notably, Manischewitz did not copy and paste ads for white audiences when it appealed to African-American consumers. Top-notch African-American entertainment figures were hired to endorse the wine. In a 1950 Pittsburgh Courier ad, popular vocal group The Ink Spots said, “Manischewitz kosher wine … Harmonizes with us — sweetly!” R&B group The Crows highlighted it in the 1953 song “Mambo Shevitz (Man, Oh Man),” which included its catchphrase, “Man, Oh Manischewitz.” And the company got none other than Sammy Davis Jr. to star in a series of TV and radio ads. The comedian and singer, who had converted to Judaism, encouraged viewers to “try some after dinner tonight. It’s delicious.” (He eventually lost the gig after Linda Lovelace revealed they’d once participated in a foursome at the Playboy Mansion.)

All this marketing nevertheless paid off. It’s estimated that by the mid-1950s, 80 percent of Manischewitz wine consumers were not Jewish. The African-American market was so important that in 1973, 85 percent of its advertising budget went to Ebony magazine, writes Horowitz. The star power gave Manischewitz the image of a sophisticated, classy product.

Although Manischewitz was decades ahead of other products in catering directly to the growing African-American middle class, what’s most notable is it did not lose its Jewish identity. The logo still featured a rabbi, with a Bible in one hand and a glass of Manischewitz in the other. Horowitz believes that being “rooted in a tradition going back thousands of years” was actually a selling point. “It’s saying this wine is about celebrating God,” he explains.“This wine is about celebrating the sacraments, the relationship between people and God.” As soul food scholar Adrien Miller told Slate in an interview, “I found that in the South, these kosher wines like Mogen David and Manischewitz are often called praise wine. And so there’s a significance to the religious culture.”

As Manischewitz cemented itself in the American cultural consciousness, it also developed its strong international market. Candice Goucher, a food historian focusing on the Caribbean, said that Manischewitz became locally popular in the ‘60s and ‘70s because “the wine fit into the flavor profile of many Caribbean drinks. It was juicy, and it was sweet.” Manischewitz has also been incorporated into many Caribbean drinks and dishes, such as Jamaican black cake.

While some of Manischewitz’s growth in this region is thanks to the Caribbean diaspora moving between American cities (where it was a common libation) and their home countries, it should be noted that the Caribbean has a long Jewish heritage, notably in Jamaica. In fact, the oldest surviving synagogue in the Americas is Mikvé Israel-Emanuel Synagogue in Willemstad, Curaçao, dating from the 1650s. Atacho remembers seeing ads and billboards for Manischewitz as a child growing up in Curaçao. Although she didn’t originally know about its Jewish connection, she wasn’t surprised to learn this fact during a high school religion class: “It’s a very multicultural island, so it was like an ‘Oh yeah, OK’ moment,” she says.

This global market ended up being crucial when wine tastes among American Jews began shifting. By the 1980s, some of these consumers developed more discerning palettes. This included a shift away from sweet wines to dryer, more European styles, with more kosher wines available to meet this demand. Still, Manischewitz didn’t lose its cultural sway. As Lauryn Hill sang on the 1994 track “Final Hour,” “Now I be breaking bread sipping Manischewitz wine.”

Within my own Ashkenazi family, it always has a place at a Passover Seder, but mostly out of a sense of obligation (and only enjoyed by a great-aunt). Horowitz describes this “disappearance” within the Jewish culinary zeitgeist as “a cultural loss.” He sees its cross-cultural appeal not only as a key part of its economic success, but also its legacy. “We don’t have Jewish or kosher products with that extent of public visibility today,” he says. “It has a place too, but the place for it is very narrow for Jews, compared to communities in which it plays a richer and fuller role in their cultural pastimes.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook