Rediscovering Lost Literary Treasures of the American Midwest

A small press is reviving forgotten—but newly relevant—writing about a complex region and its people.

Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio is a classic of American literature for its evocation of small-town life. But few people have heard of Anderson’s Poor White, published just a year later.

The release of Winesburg, Ohio’s spare short stories in 1919 made Anderson famous, while the sprawling novel Poor White has been mostly overlooked. Now, though, it’s coming back into print, as one of the first books in a new series, Belt Revivals, that aims to resurrect “classic, unjustly forgotten Midwestern titles” and introduce them to new readers.

Anderson’s novel is an “odd book but a great one,” says writer John Lingan in the new edition’s introduction. Reading Poor White after Winesburg, Ohio “feels like leaving a one-room log cabin for a taxidermy-festooned hunting lodge; there’s a shared sensibility, a familiar woodsy style, but the scope and intention aren’t even comparable.”

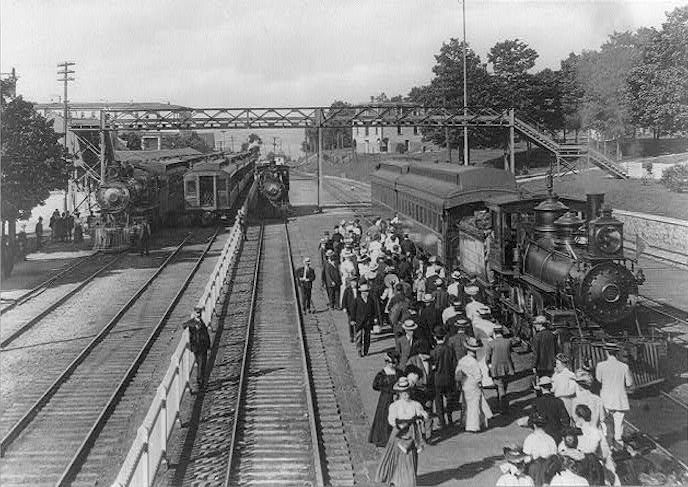

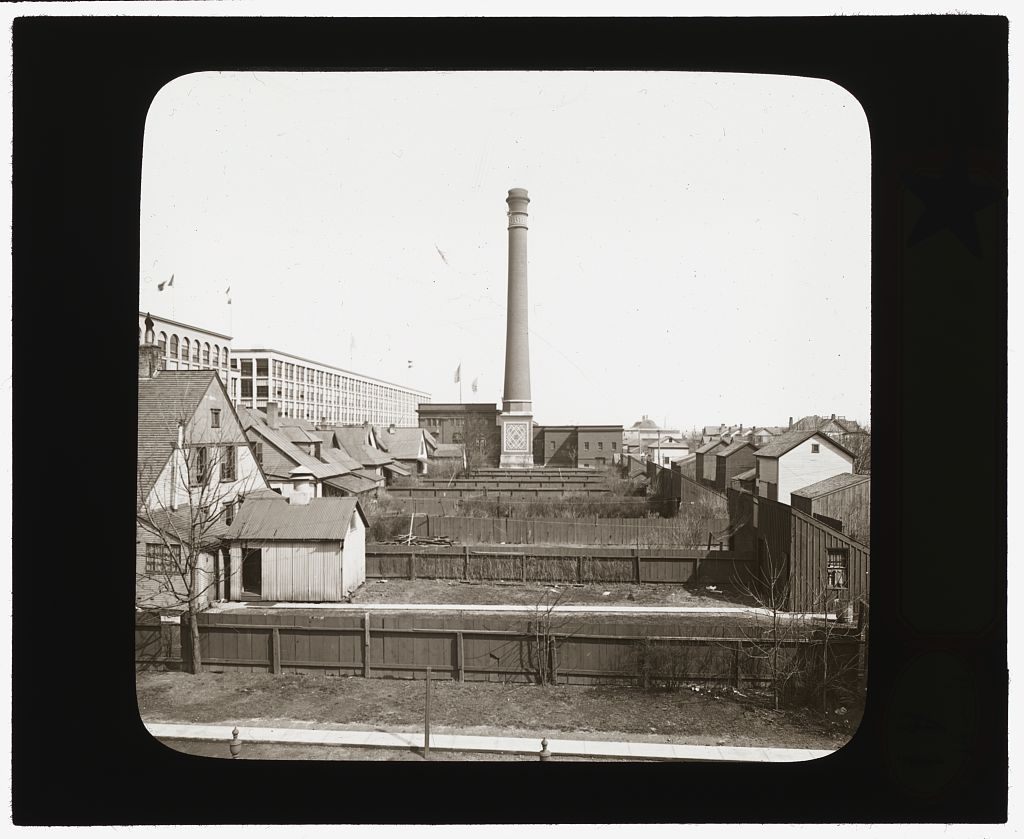

Poor White follows Hugh McVey, who begins life as an oafish layabout, to the industrializing Midwest of the late 19th century. He’s a country boy in search of a tidy town to host his growing ambitions, and he’s the sort who takes notice of the roar of the Mississippi River and the rolling landscape. “One of the greatest pleasures of Poor White is Anderson’s crystallization of his native Midwest at the very moment of its romantic enshrining,” Lingan writes.

Though the book doesn’t reify either the region’s rural roots or its industrial future, its portrayal of the Midwest still has the power to shape a reader’s ideas about the region. That’s a primary aim of this new series, which is kicking off with Poor White and Hamlin Garland’s Main-Travelled Roads, a collection of short stories about the rural Midwest in the 1890s. Three more lost classics will follow.

A Belt Revival book, says Anne Trubek, the founder of Belt Publishing, “has some contemporary resonance. There are some themes that are newly interesting to people or eerily familiar.” Though written in the late-19th and early-20th centuries, these titles should have relevance in 2018. Another criteria: “It’s a work that deserves another chance at an audience,” she adds.

Belt, a small press with a regional focus, was founded in 2013, after Trubek began to understand the need for more stories about the Midwest. With Richey Piiparinen, an urban researcher, she put out a call for essays about Cleveland. “It was a really simple idea,” she says. “We asked a bunch of people if they had a story to tell about Cleveland. We were overwhelmed with submissions. There are interesting things happening in this place now and in the past, and there hasn’t been as much written about it.”

Trubek had been teaching at Oberlin College but had started writing for a wider audience, outside of academia. “There’s so little publishing or media from the Rust Belt,” she says, “and there’s so much pent-up desire, not only to tell stories but to hear stories and read stories about these places.” Belt Publishing’s city anthologies now include Detroit, Youngstown, Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, Flint, Akron, and Buffalo, in addition to the inaugural volume on Cleveland. The press followed this series with neighborhood guidebooks to select cities, as well as nonfiction works on Appalachia, Midwest folktales, “how to speak Midwestern,” and more—all Midwestern in focus but broad in potential appeal. In 2013, Trubek also created Belt Magazine as forum for beautifully crafted stories about politics and culture from the region.

As an academic, though, Trubek always had a soft spot in her heart for American novels of the late-19th and early-20th centuries. She had read them for her dissertation in American literature, and had long thought that some of the more overlooked titles were due to be republished. After the 2016 election, political thinkers, commentators, and reporters turned a close eye to the Midwest, and these books, she hoped, might help expose the roots of issues that have resurfaced today—and introduce outsiders to the complexities of the region and its people.

Ultimately, though, the main reason to republish these books is that they’re worth reading. Poor White might be thought of as a “flawed masterpiece,” Trubek says—the plot gets weird—but the writing is vivid, compelling, and revealing. “We are really interested in fabulous writing,” Trubek says. “People think a regional press has to be booster-ish or sentimental or not that sophisticated. There’s no reason for that to be the case.”

Poor White’s thoughts on wealth and fortune might feel contemporary, but that alone wouldn’t be enough if a reader wasn’t compelled to find out what happened to Hugh McVey, “born in a little hole of a town stuck on a mud bank on the western shore of the Mississippi River in the State of Missouri.” It’s a foreboding beginning for a story that pays careful attention to what it meant (and means) to live in the Midwest, open to both its charms and its challenges.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook