Londoners Once Wondered If Feral Hogs Roamed Victorian-Era Sewers

Lots of legends seem to start underground.

For the most part, sewers are designed to be invisible and easy to ignore—assuming that nothing goes wrong. There is some comfort in believing that the world stops at the ground beneath our feet. What’s down there in a sewer pipe can be hard to imagine at all, beyond the vague impression of something damp, dripping, and foul.

In London, and other cities all over the world, this ignorance is a fairly recent luxury (and in many modern places without sewer systems, it is still not possible at all). That may be why, in 18th- and 19th-century London, tall tales of what might be down there ran amok. It must not have seemed like such a stretch to imagine herds of feral hogs stampeding through the muck.

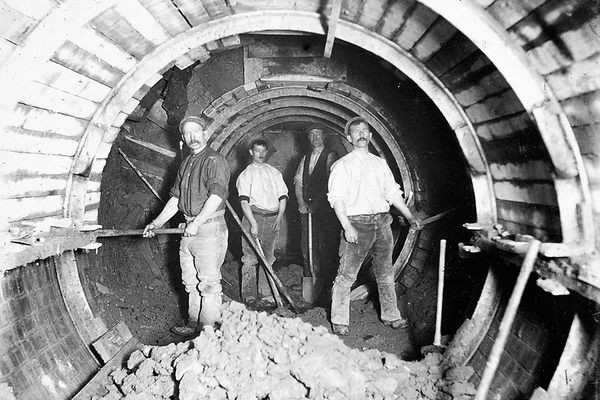

The city’s nascent sewer system was overtaxed and constantly breached its limits. The network was overhauled and markedly expanded after the Great Stink of 1858, when deposits that the sewers had spit out into the River Thames baked in the summer heat, to the stomach-roiling chagrin of the entire city.

The journalist Henry Mayhew was unfortunately familiar with the contents of the city’s subterranean guts. He spent the 1840s documenting the lives of the city’s mudlarkers, rat-catchers, food vendors, and other working folks, and the sewers came up a lot in his series, which was compiled into a multivolume set, London Labour and the London Poor, first published in 1851. During the spring tides, Mayhew wrote, fetid liquid “burst up through the gratings into the streets,” until the low-lying neighborhoods around the Thames “resembled a Dutch town, intersected by a series of muddy canals.” He also spoke to “sewer hunters,” or people who made their livings on other people’s leavings.

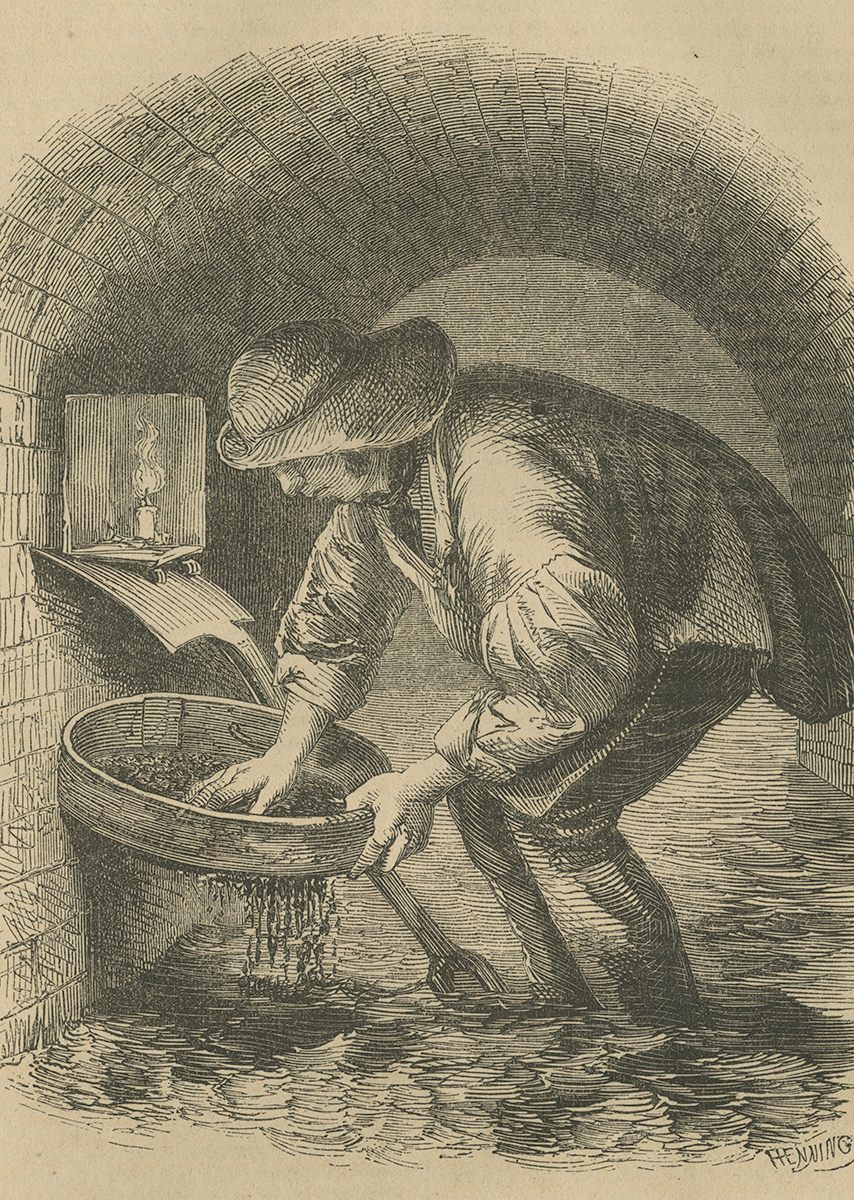

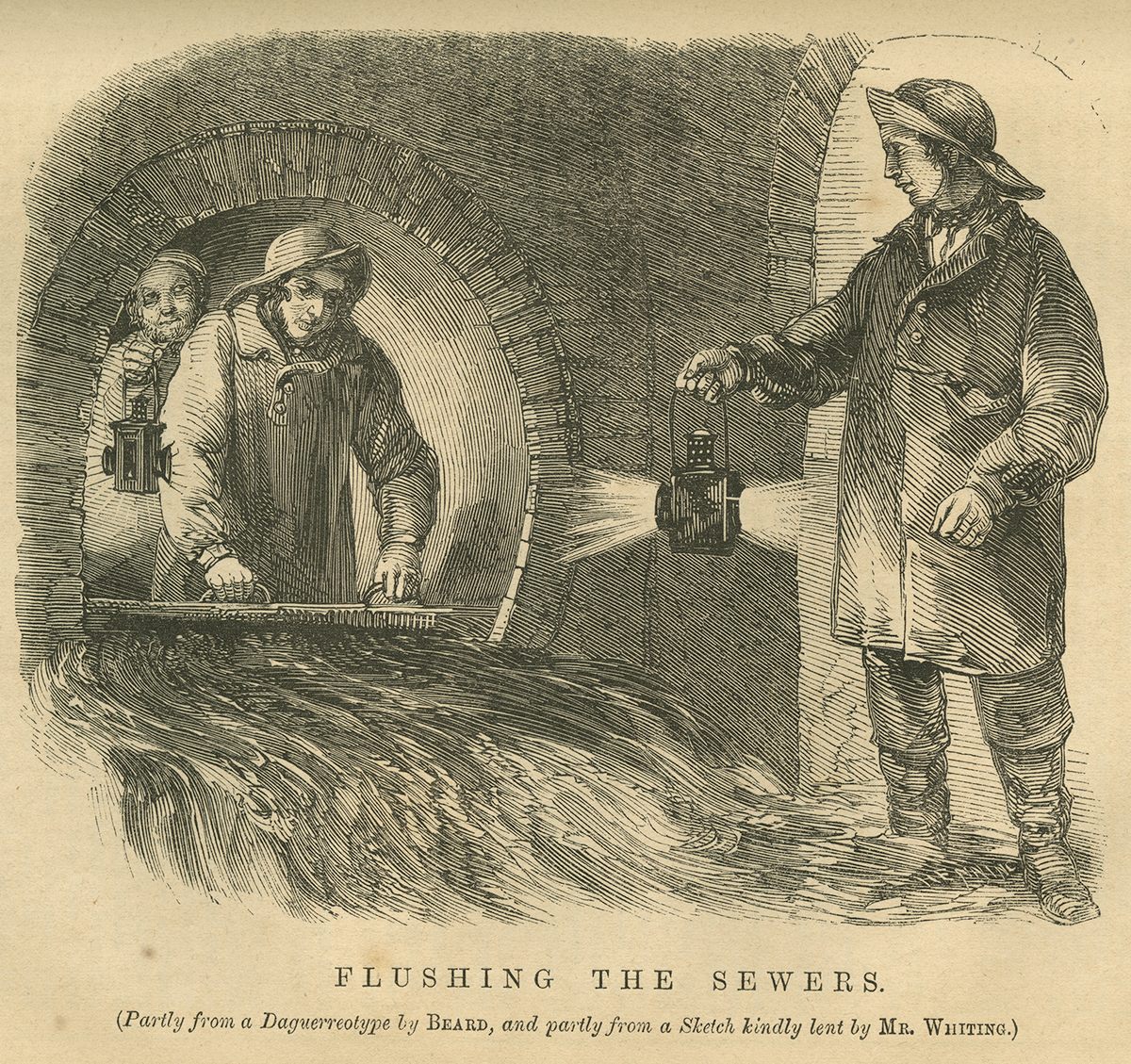

To hear Mayhew tell it, they were busy. “Some few years ago, any person desirous of exploring the dark and uninviting recesses,” Mayhew wrote, could walk right in one of the pipes that emptied into the Thames “and wander away, provided he could withstand the combination of villainous stenches which met him at every step, for many miles, in any direction.” The sewer hunters—whom Mayhew also referred to “shore-workers” and “toshers” on account of their habit of scouring the sewers and river shore for “tosh,” or anything made of copper—descended when the tide went out (at least until the pipes were closed off by iron gates or doors). They traveled in groups, he wrote, to defend themselves from rats, strapped lanterns to their chests, and raked the mud with long-handled hoes to find any money, nails, or metal scraps that may have gotten lost and lodged down there.

It’s hard to know what to make of Mayhew’s stories. They’re simultaneously visceral, gritty, spectacular, and specific—far-fetched, certainly, but also full of quotes, measurements, and rich observations. But at least one of them—one that would strike many readers then and now as patently ridiculous—seemed just on the edge of possibility. Mayhew claimed to have heard it from a sewer-hunter, but not any one of them in particular. Mayhew couched it in the language of myth, calling it “a strange tale in existence among the shore workers.”

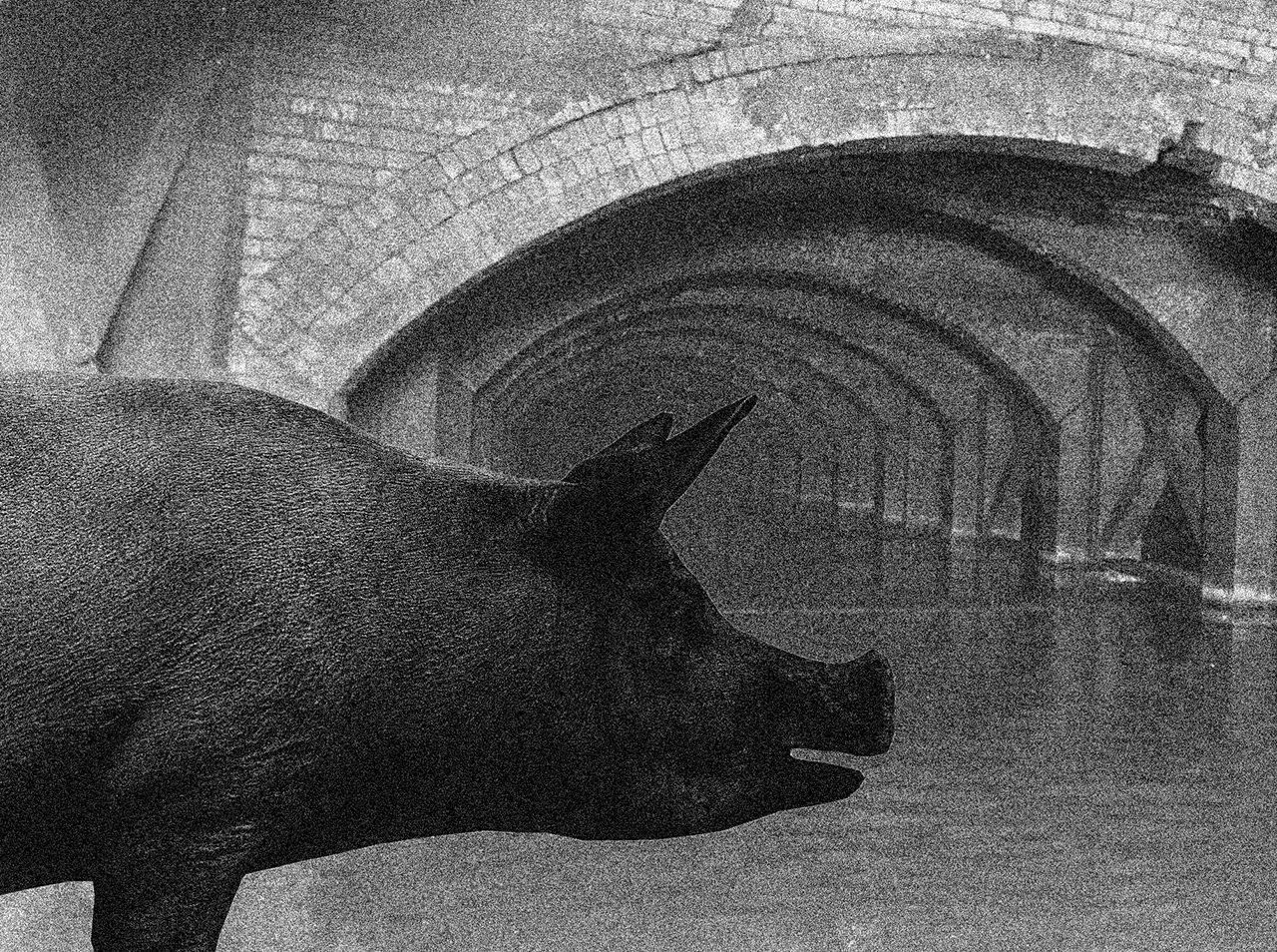

The gist, as he recounted it, with some measure of doubt, is that a pregnant sow had roamed into the sewer somewhere near Hampstead, and then delivered and raised her offspring in the pipes. Feasting on “the offal and garbage washed into it continuously,” Mayhew wrote, “the breed multiplied exceedingly, and have become almost as ferocious as they are numerous.”

Is Mayhew to be believed at all? “He’s quite a regularly quoted source from that time in London, and I think that might be because there aren’t an awful lot of other similar accounts of working-class people,” says Laurence Ward, head of digital services at the London Metropolitan Archives and lead curator of the institution’s exhibition Under Ground London, which touches on the legend of the sewer swine. “People looking for human voices often go to him.” Mayhew’s stories appear rigorously reported, but some things don’t quite add up, Ward says. Some of the illustration captions in his book, for example, note that the images are based on daguerreotypes, which Ward finds suspect. “Think about the process of trying to take a photograph in a dark sewer—by candlelight, presumably,” he says.

Still, it wasn’t the first or last time that a reporter offered a story about underground swine in London. A version of the tale is at least as old as a 1736 account of a boar dodging a butcher’s blade somewhere near Smithfield Bars, and then feasting in the sewer for five months before emerging from Fleet Ditch. In the 2008 book London Lore: The Legends and Traditions of the World’s Most Vibrant City, author Steve Roud cites the legend’s reappearance in a Daily Telegraph article from October 1859. The story dangled the tantalizing possibility of “undiscovered patches of primeval forest in Hyde Park,” and also the idea that “Hampstead sewers shelter a monstrous breed of black swine, which have propagated and run wild among the slimy feculence.” Roud points out that it’s not entirely clear whether the Telegraph writer was just parroting Mayhew, or had heard it afresh from someone else. It has all the spectacle, bombast, fuzziness, and distant possibility of other related legends, such as the one about alligators swimming through New York City’s pipes.

When Mayhew told the story, he hedged his bets: Isn’t it odd, he noted, that the residents never seem to glimpse the hogs’ hides through the grates? That they never hear grunts beneath their feet? Even so, “This story, apocryphal as it seems, has nevertheless its believers,” he wrote.

It’s not hard to see why. At the time, London was lousy with livestock markets, and many sewers were wide open. “If there are so many animals kind of out in the city, and they had access to the ditches and the sewers … it all seems quite plausible in that sense,” Ward says. “Whether they could breed in the sewers and develop a race of sewer pigs is kind of another matter altogether.”

The emergence of the myth could also be a product of frustration with the inadequacy of parts of the city’s infrastructure, and the way that planned improvements were mangling the landscape all around. They were sorely needed and widely welcomed, but they still left scars. In 1859, the British-born writer Richard Rowe, who often wrote for Australian newspapers under the pseudonym Peter Possum, lamented in The Sydney Morning Herald that construction of sewers and railways, necessary as they were, “have played sad havoc with the country around London.” He saw trampled landscapes, and mustered violent language to describe them, complaining of “cannon-like drained pipes” that “crash the nettles in the ditches,” and “raw red entrances to tunnels,” like wounds. Perhaps then a little wild natural revenge from down below made some kind of cosmic sense.

“The reader of course can believe as much of the story as he pleases,” Mayhew wrote, before washing his hands of the sewer pig saga. Maybe there was a kernel of truth to it, maybe there wasn’t. Back then, the line between the underground world and the above-ground one was murky and permeable. Today, unless a fatberg stoppers a pipe and makes news, Londoners are more removed from the sewage moving beneath their city. But subterranean spaces and sewers in particular—with their mysteries, their unfamiliarity, their fascinating grossness—continue to pull our imaginations down below.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook