How to Take a Literary Pilgrimage in the Real World

First get lost in the pages, then get lost in the places.

Visitors to Jane Austen’s House Museum, in Chawton, England, always seem to have a strong reaction to her writing table.

The table is no particularly dazzling feat of construction or design. It’s walnut, with three legs and 12 sides—solid, humble, and right at home in an 18th-century cottage or manse. But visitors who see it are visibly moved. Sometimes the table even becomes the site of something like a seance, as if guests can feel Austen there with them, glasses sliding down her nose as her quill skitters out characters, foibles, and scenes of tangles and triumphs. Visitors aren’t allowed to touch the surface, but they seem to ache to do so, “as if the wood itself contains something of Jane,” Madelaine Smith, the museum’s former marketing and events manager, has written. “Some visitors hold their breath. Others cry.”

Those visitors vastly outnumber Chawton’s 445 residents. Despite just one school and a single church, it has become, as The New York Times put it, “a mecca for Janeites.” Pilgrims come from near and far to sit in the pews where Austen would have heard sermons, sit in the shade of an oak tree said to be descended from one the writer planted, or wander the brick house where she spent the most of the last eight years of her life in a period of dizzying literary productivity, completing Pride and Prejudice, Sense and Sensibility, Emma, and more.

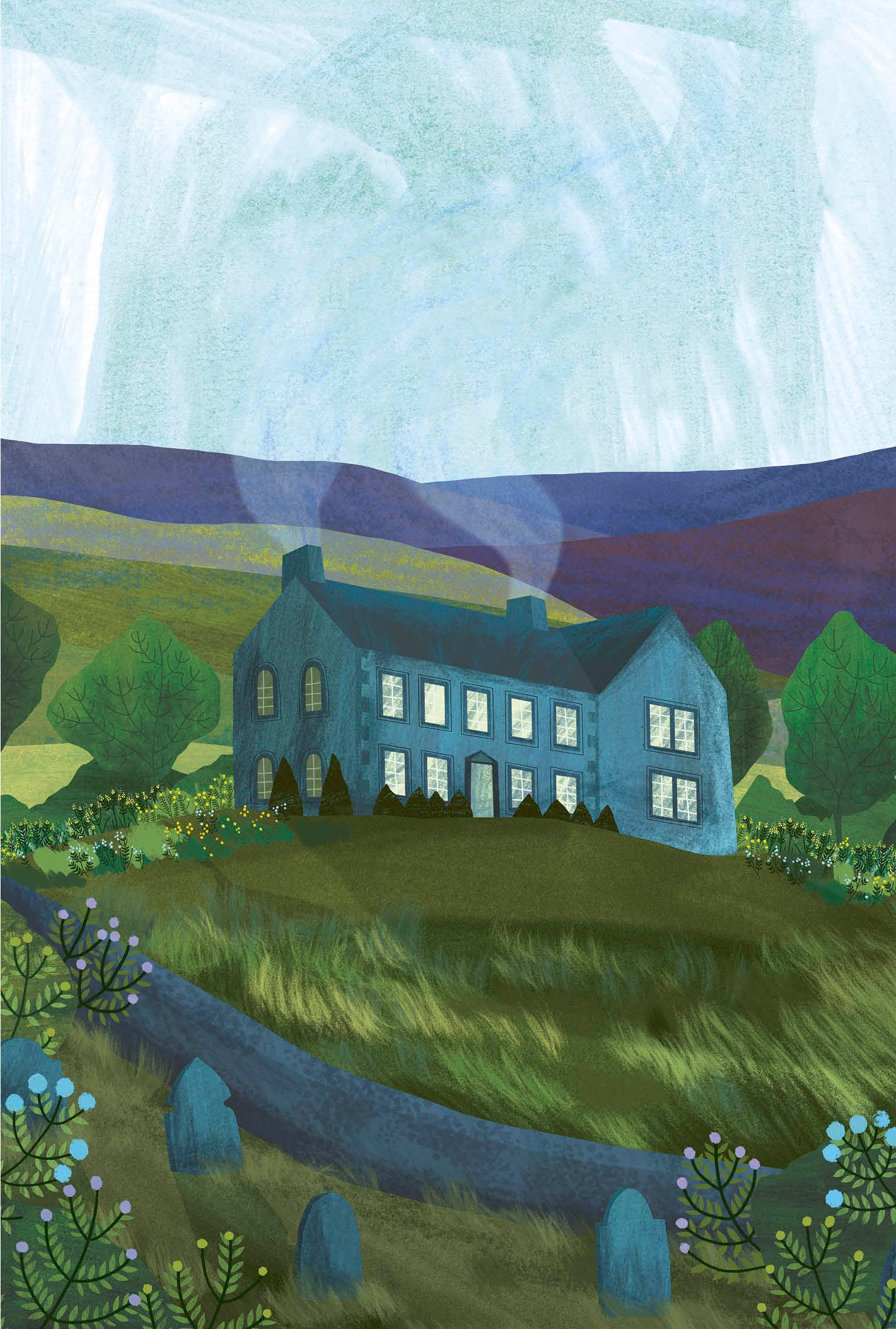

Literary pilgrims may set out to pay homage to an author, or to retrace the routes of their favorite characters. The new book Literary Places, by Sarah Baxter, celebrates the second approach, with a focus on streets, shops, and boulevards that exist in the real world. Janeites will find a guide to Bath, England, as trod by Austen’s heroine Catherine Morland in Northanger Abbey. Charming illustrations by Amy Grimes preview what awaits readers near the shops on Milsom Street or the leafy Gravel Walk. As in Chawton, part of the appeal is that it can seem as though little there has changed. To stroll the town’s “golden streets now is to almost step straight back into Austen’s pages, minus the bonnets and breeches,” Baxter writes.

Readers of the book can drop in to visit the Saint Petersburg where Raskolnikov stalked around in moral agony in Crime and Punishment, or the courthouse in Monroeville, Alabama, where Nelle Harper Lee watched her lawyer father at work long before she wrote To Kill a Mockingbird. (Each spring, visitors can watch a performance of the play based on the novel, from the seats where Lee once sat.) A trek to the windy, wild moors conjured in Wuthering Heights might involve a stop at the Brontë Parsonage Museum, and a visit to Top Withens and Ponden Hall, two homes thought to be the likely candidates for Thrushcross Grange and the novel’s namesake manor, respectively. (And if you happen to have £1,250,000 to spare, you can buy Ponden Hall yourself.) A visit to the Paris of Les Misérables may include a ramble through the Jardin du Luxembourg, full of pear trees and chirping birds. Happily, the rank, hellish sewers through which Jean Valjean hauls a wounded Marius have been cleaned up, but are sealed to roving bibliophiles. (A museum about the smelly, slimy tunnels is currently closed.)

When literary attractions don’t have specific real-world corollaries, Baxter gives a best guess or alternate suggestion. The setting of Gabriel García Márquez’s novel Love in the Time of Cholera is unknown—somewhere, we’re told, near the Caribbean Sea—but Baxter finds a kinship with Cartagena, where the Plaza Fernandez de Madrid is just as dreamy and dappled as the Parquecito de los Evangelios. Fans of Ulysses who travel to Dublin won’t find The Burton, Leopold Bloom’s favored haunt, but Baxter suggests tucking into the character’s preferred Gorgonzola sandwich at Davy Byrnes pub, nearby.

Literary pilgrimages can take many shapes: a tour of an author’s historic home, a day hike to a stirring site, a road trip to relive a beloved story. Love of literary places can also lead to changes in the real world, such as the establishment of museums or organized tours in otherwise sleepy neighborhoods that find themselves with the economic boon of an attraction. Fans might also be inspired to create places that don’t otherwise exist, or transform historic literary places into inspirations for new generations of writers.

A few years ago, as home prices climbed in Harlem, some residents worried that Langston Hughes’s former brownstone on 127th Street would be lost—subsumed by condos and coffee shops. Hughes’s poems had inspired author Renée Watson to pursue her literary career, so when she moved to New York, she made a beeline for Harlem, eager to visit where he lived and the places he described. Everything, she said, felt so familiar. “I saw myself and my neighborhood and the people in my family in the stanzas of his poems,” Watson told CBS News. “It was like the first time when I really saw my reflection in a piece of writing.” When she found that Hughes’s home was sitting vacant—privately owned and closed to the public—she saw an opportunity. In 2016, Watson launched a campaign to raise money to lease the home and use it as a hub for arts and activism. Now, the I, Too Arts Collective—which takes its name from a Hughes poem—hosts dance classes, creative drop-ins and workshops, book release parties, and salon-style readings, and collects supplies for local shelters. It’s what happens when a place of literary history looks to the future.

The old adage is that books can be transportive—that readers can get lost in the world of sentences and paragraphs, scenes and ideas. This can be literally true when readers retrace the steps of an author or character in a three-dimensional place they’ve only seen in either their mind’s eye or in small, black font. And that experience can be transformative, too.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook