Launching Spaceship Earth

The true, stranger-than-fiction, adventure of eight visionaries who spent two years quarantined inside of a self-engineered replica of Earth’s ecosystem called Biosphere 2. Premiering May 8th.

Spaceship Earth is the true, stranger-than-fiction, adventure of eight visionaries who in 1991 spent two years quarantined inside of a self-engineered replica of Earth’s ecosystem called Biosphere 2. The experiment was a worldwide phenomenon, chronicling daily existence in the face of life threatening ecological disaster and a growing criticism that it was nothing more than a cult. The bizarre story is both a cautionary tale and a hopeful lesson of how a small group of dreamers can potentially reimagine a new world.

RSVP HERE: LeVar Burton Moderates a Conversation on ‘Spaceship Earth’

Join us Saturday May 9 at 8 pm EDT on our Facebook page for a Live Q&A session moderated by Levar Burton. Spaceship Earth director Matt Wolf and Biospherians Mark Nelson and Linda Leigh will join us to talk about the film and their experience embarking on this revolutionary experiment to change the world.

Stream the film from home starting May 8.

Director Matt Wolf on how creating the film has helped him find wonder and curiosity in the world

A few weeks after I finished making Spaceship Earth, I needed a mind cleanse, so I decided to watch the landmark British documentary The Up Series. In 1964, the filmmaker Michael Apted got a group of fourteen 7-year-olds together in London, and he asked them to talk about their lives. The first installment, Seven Up!, was meant to be a one-off broadcast about UK class disparity, but it evolved into one of the most epic documentary experiments of all time. Every seven years, Apted would reconnect with his subjects to show how their lives changed. Last year, the ninth installment was released, and the 7-year-olds are now 63. Most people have watched the series in installments over the past five decades—I watched it in four days

My friends called it my “7 Up Obsession,” but what I was doing—unconsciously or not—was simulating the passage of time. I was transfixed, and I needed to find out what happened next in the course of these ordinary lives. Their stories aren’t very dramatic, but to see a person’s lifetime of wisdom, hardship, ambivalence, and hope compressed into a concentrated period of hours is profound.

I guess I wasn’t actually taking a break from Spaceship Earth, because in a lot of ways, this is what my film is about. We follow a very unusual group, who call themselves “synergists,” from the time they meet in the 1960s as young idealists until today. During that half century, they built an enormous ship and travel the world, start a performance troupe called The Theater of All Possibilities, and they create a miniature replica of the planet in a geodesic pyramid in the Arizona desert.

It’s amazing to watch footage of the synergists growing up, to see their evolving hairstyles and fashion over the decades. You can see when certain periods in their lives are exhilarating, and when others are more trying.

When I was making Spaceship Earth and watching The Up Series, I was thinking a lot about what imprint I might make on the world, and which relationships in my life will last (you know, the light stuff). Now that my 7 Up obsessions is over, I’m onto the next documentary epic, Eyes on the Prize—the seminal fourteen-hour history of the civil rights movement. But I also do time travel in less cerebral ways, like reorganizing all the shelves and drawers in my house during a global quarantine.

Still there’s one thing I’ve been doing to simulate the passage of time for my entire adult life. Starting when I was 18-years-old, I wrote a letter to myself on New Year’s Eve. Each year, I write a new letter after reading all the previous years’ in chronological succession. Twenty years later, this tradition has been going on for over half of my life. Each year, I have the opportunity to literally see myself grow up, and to take stock of my life. Obviously crazy things happened (remember 9/11?), but over the course of these two decades, what’s most surprising is how much stays the same. I think that’s true of the synergists in Spaceship Earth—they’ve led epic lives full of adventure and experimentation—but in the end, what they have left is each other

—Matt Wolf

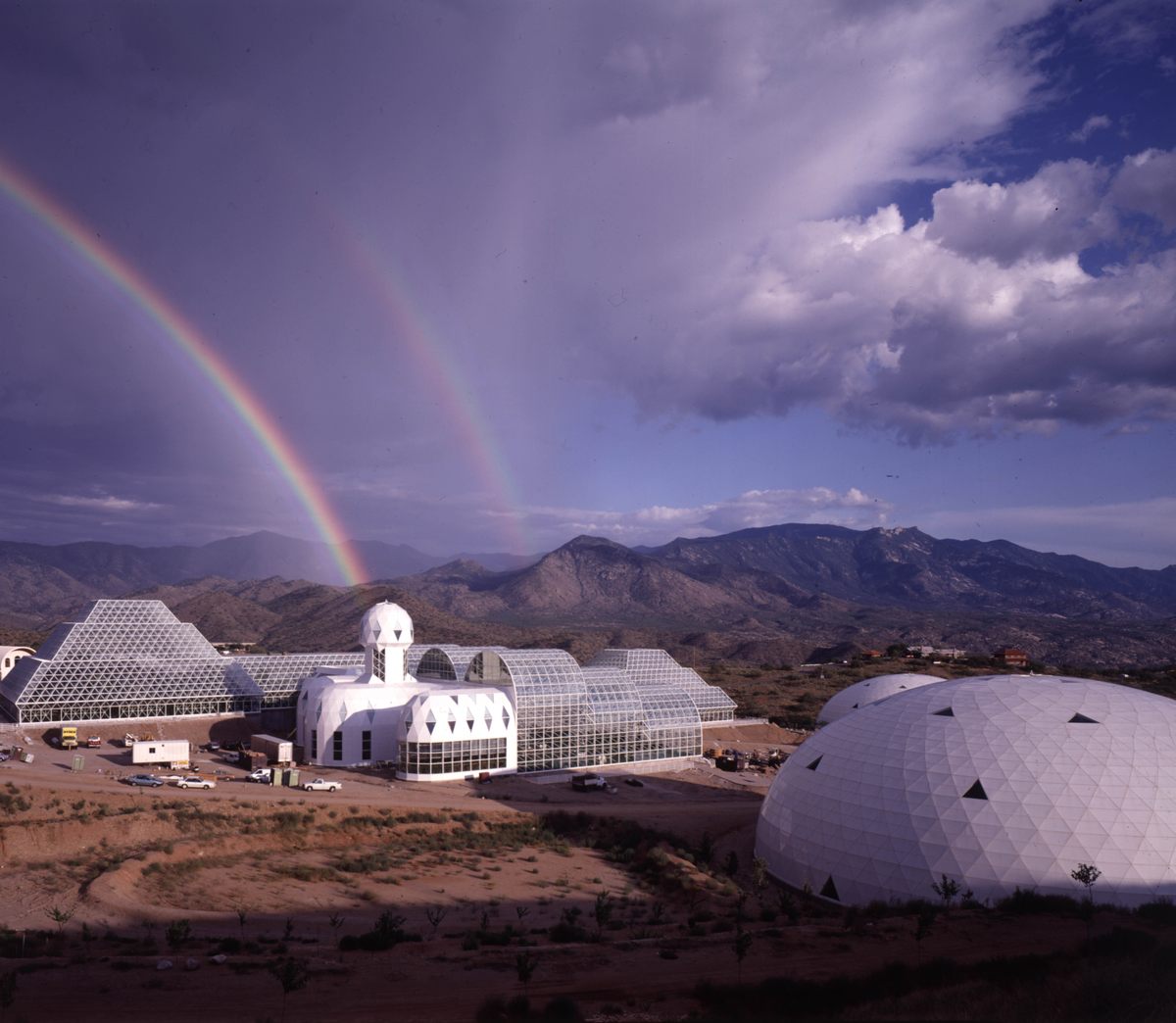

Earth 2.0: How a voluntary 1990s quarantine experiment captured the world’s attention

The adage about truth being stranger than fiction is exemplified in the odd—but true—tale of a largely self-contained experiment in the desert. Starting in 1991, eight people lived for two years and 20 minutes in a microcosm of Earth—dubbed Biosphere 2—on a 40-acre plot of land in Oracle, Arizona. The glass terrarium-like structure covered seven million cubic feet (that’s 3.14 acres) and included seven distinct biomes: a rainforest, ocean, mangrove wetlands, savannah grassland, fog desert, an agricultural system and human habitat. The experiment’s mission was to simulate a closed system to see if humans could live somewhere else in the universe.

The four-year construction process on the sealed greenhouse began in 1987, and the public followed it with interest. Calling it “Noah’s Ark: the Sequel,” Time magazine wrote of the “gleaming, 26-meter- high (85-ft.) cathedral-like latticework roof of steel tubing and glass,” how it is “both an architectural wonder and a scientific tour de force,” and how the Biospherians would be “sealed inside for two years, getting nothing from the outside but information, electricity and sunshine.” Discover called it “the most exciting scientific project to be undertaken in the U.S. since President Kennedy launched us toward the moon.” The night before the crew stepped into the structure that would be their home for two years, 2,000 revelers including psychedelic drug advocate Timothy Leary and actor Woody Harrelson attended a party to celebrate the launch.

The first day of isolation was marked by pomp and circumstance: blessings were issued by a Crow Indian shaman, a Tibetan Buddhist monk and a Mexican dancer burning incense before the jumpsuit-clad crew entered and the air-lock door was closed by Bass, who funded the $150 million project, complete with 3,800 species of plants and animals.

Things seemed to go well initially, but challenges quickly became clear. The team was supposed to raise their own food—and demonstrated success growing crops including rice, papayas, sweet potatoes and bananas—but cloudy weather made it difficult, and the inhabitants had to break into an emergency food supply. Information began to leak that engineers installed a carbon dioxide scrubber and that staffers were making twice-monthly deliveries of necessities like mouse traps and seeds to combat pests and failing crops. Many members of the crew lost a dramatic amount of weight and interpersonal tensions threatened to boil over. Outside intervention became necessary when soil bacteria proliferated, driving up the concentration of carbon dioxide to 12 times the air outside. Free oxygen levels plummeted and the crew became ill and disoriented (a condition similar to altitude sickness). In January 1993, thousands of pounds of liquid oxygen had to be pumped into the structure.

When the original Biospherians emerged on September 26, 1993, they were a gaunt, rag-tag bunch. The following year, a second crew attempted to live in Biosphere 2, but they were plagued by similar challenges and only lasted from March to September. The highly-publicized project remains the largest closed system ever constructed, a mash-up of Big Brother, The Truman Show, The Martian. Though the experiment failed to prove that humans could survive in a similar structure in outer space, it did pioneering work in the realm of water recycling and other fields of study.

Today, Biosphere 2 is managed by the University of Arizona and researchers study things like the effects of the ocean’s acidification on coral and ensuring food and water security. Fascinated by this too-strange-to-believe saga? The 2020 documentary Spaceship Earth offers a vivid deep-dive into the crew’s day-to-day—as well as the cult-like group dynamics—and offers insights into this both hopeful and peculiar story of scientific discovery, conservation and human-will.

Elsewhere on Atlas Obscura

Want to learn more about Biosphere 2? You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Take a virtual tour of the now non-sealed biosphere and get a closer look at the over 3,500 exotic species growing in the dome today.

Read more about Biosphere 2 and plan a future visit to experience the dome first-hand in Arizona.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook