Why Scientists Are Worried About a Landslide No One Saw or Heard

It’s all about climate change, retreating glaciers, and newly exposed rock.

If a steep mountainside in a remote national park gives way and drops 200 million tons of rock into deep glacial water, will anyone hear?

In the case of the massive landslide that fell into Taan Fjord, Alaska, the answer was no—and yes.

No one heard the mountainside fall into the fjord on a rainy night on October 17, 2015. No one saw an almost unimaginably huge and powerful wave crest at 600 feet and sweep down the inlet. The tsunami obliterated forests on both sides of the inlet, and its rush to the sea dragged an iceberg over a marine spit and out into coastal Icy Bay. The enormous wave traveled eight miles to open water and made it all the way to about five miles north of Icy Bay Lodge.

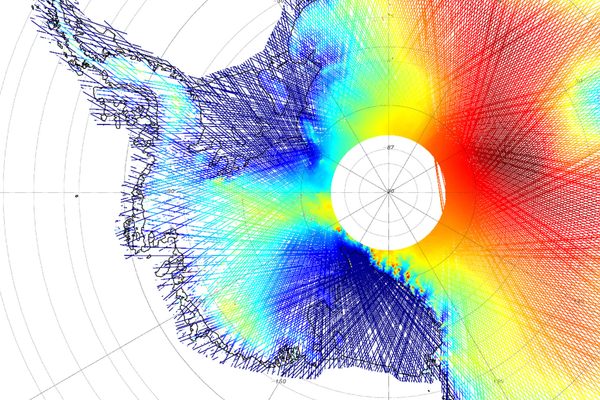

Thousands of miles away, at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory north of New York City, a pair of geologists noticed an unusual squiggle on a seismograph. The team of Göran Ekström and Colin Stark has in recent years pioneered a new method of detecting unusual seismic events that don’t send out the fast-moving compressional waves characteristic of earthquakes. Instead they look for subtler surface waves, or undulations, that radiate much more slowly through the surface of the earth. These are the kinds of waves sent out by collapsing volcanoes, calving ice sheets, and massive landslides.

“There are not that many landslide detections by us in a given year, maybe just half a dozen,” says Ekström. “We now know that when we detect something, it is often spectacular. We had just detected another landslide in the Yukon a week earlier, and had it confirmed, so I was quite excited when I saw another detection in the Saint Elias range, especially since it was not detected by anyone else, and because it was so large.”

Few landslides and only one wave in the written history of North America can compare. About 150 miles to the south, also in southeastern Alaska, a major earthquake in 1958 loosened a steep mountainside high above Lituya Bay and dropped it thousands of feet into a narrow inlet, creating a “megatsunami” over 1,700 feet high, killing two fishermen.

It’s not a coincidence that both colossal landslides and subsequent tsunamis occurred in the Saint Elias mountains. At over 18,000 feet, Mount Saint Elias stands taller than any other mountain in a coastal range on the planet. The peak towers just 13 miles away from the site of the Taan Fjord landslide and tsunami. In the last five years, five monstrously large landslides have been recorded in these rapidly uplifting mountains, totalling hundreds of millions of tons of rock.

“It’s the land of hyperbole,” says Andrew Mattox, a geologist who helped lead expeditions to the tsunami site in 2016. “Saint Elias is the second-highest mountain in both the United States and Canada, and hardly anyone has heard of it. It’s a mean mountain. The weather off the Gulf of Alaska is legendarily horrible. It’s steep and rugged, with huge glaciers. Icy Bay [near Taan Fjord] was full of glaciers as recently as 100 years ago.”

Because glaciers are retreating rapidly in these mountains, experts expect more such colossal landslides and tsunamis.

“It is plausible that there will be more large landslides as the climate warms,” Ekström says. “First, there is water around, and water tends to destabilize mountains slopes. Second, and probably an important factor for the Taan Fjord landslide, the retreat of glaciers removes the buttressing effect of glaciers in these steep valleys, also destabilizing the slopes.”

As the climate warms, glaciers retreat, and the slopes they carved out of the rock are exposed. As recently as 1961, the Taan Fjord was filled to its mouth at Icy Bay by the Tyndall Glacier, which at one time stood as much as 1,000 feet high. In a little over half a century, the Tyndall Glacier has retreated ten miles up the fjord, away from the ocean. Today, the raw rock slopes it left behind stand open to the weather. The 2015 landslide, and the risks its collapse revealed, drew tsunami experts from around the world.

Bretwood “Hig” Higman, a tsunami expert from Alaska who oversaw a major scientific expedition to the site last summer for Ground Truth Trekking, is one of many tsunami researchers who’ve been contemplating ways to reduce the risks of disaster.

“We can look at this as an analog to what could happen in places like [nearby] Glacier Bay, where there are steep slopes and deep water inlets where cruise ships with two or three thousand people visit in the summer, and fjords in Norway where communities could be threatened by this sort of tsunami,” he says. “The next step is to build an accurate scientific picture of what is happening, and get specific. Say you have a cruise ship in Glacier Bay. With better models, there might be some ability to provide warning, or there may be areas where a ship could be in the bay without much worry. In other parts of the fjord, there may be bad places to be in case of a tsunami.”

Bre MacInnes, a tsunami modeler who was part of the Ground Truth expedition, worried that another landslide might fall while they were at the site of the October 2015 tsunami.

“In all honesty I was nervous,” she says. “There’s no reason it couldn’t happen again. We were all talking about it. Everyone had mapped a way they would run if we started hearing loud sounds from the glacier.”

Higman, who spent weeks at the site, continually tried to picture what happened during the moments of the event. He says it became a very real and intense experience, like seeing a massive volcano erupt and build toward the sky, but all in an instant.

“At the beginning it’s not really a wave so much as it is an impact crater,” he says. “You get a crater in the water, and as we know water wants to be flat, and at that instant it is very very not flat. You get a splash 100 meters high, and a hole in the water, and huge quantities of rock. For a brief moment when the landslide enters the water it creates a bubble big enough to fit an entire small town inside of—it’s an incredibly dynamic 60 seconds. In the ensuing moment it forms a fairly conventional wave, a big hump with a trough behind it, moving down the fjord.”

Andrew Mattox says he couldn’t really understand the power of the tsunami until he clambered a difficult 600 feet up the side of the steep inlet slope, surveying the so-called “run-up.”

“I’m a geologist and I’d say it was one of the most impressive events I’ve ever seen the aftermath of,” he said. “At the mouth of the fjord, the tsunami scraped everything off the rock—the trees, the soil, everything. It wasn’t until I reached the top that I realized how big this was and had a sense of the unimaginable destructive force. And it all happened in a matter of minutes.”

Higman still thinks about the tsunami, which was an estimated 40 feet high by the time it reached Icy Bay, about eight miles from the landslide’s fall into the fjord.

“Right around the corner is Icy Bay Lodge,” he says. “It was night and it was raining and I picture guests in there streaming movies and only realizing what happened when they came out the next morning and found loads and loads of shredded forest coming out into the bay.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook