When Americans Dreamed of Kitchen Computers

The ultimate appliance turned out to be expensive and impractical.

Who is making dinner?

This is a question many American families find themselves asking daily. It’s not a new question, either. Generations have debated the delegation of kitchen duties, often touching on class, race, and especially gender. Most frequently, women have taken on home cooking, which often means hard work for little or no pay. Proposed solutions have ranged from equitable sharing of household labor between all family members, buying pre-made foods, and even kitchen-less homes and communal cooking.

However, one solution to the cooking dilemma has remained in the American cultural imagination: a kitchen computer, one capable of preparing a family’s every meal. Though it might seem like something straight out of The Jetsons, there was a brief period where the kitchen computer was very real indeed.

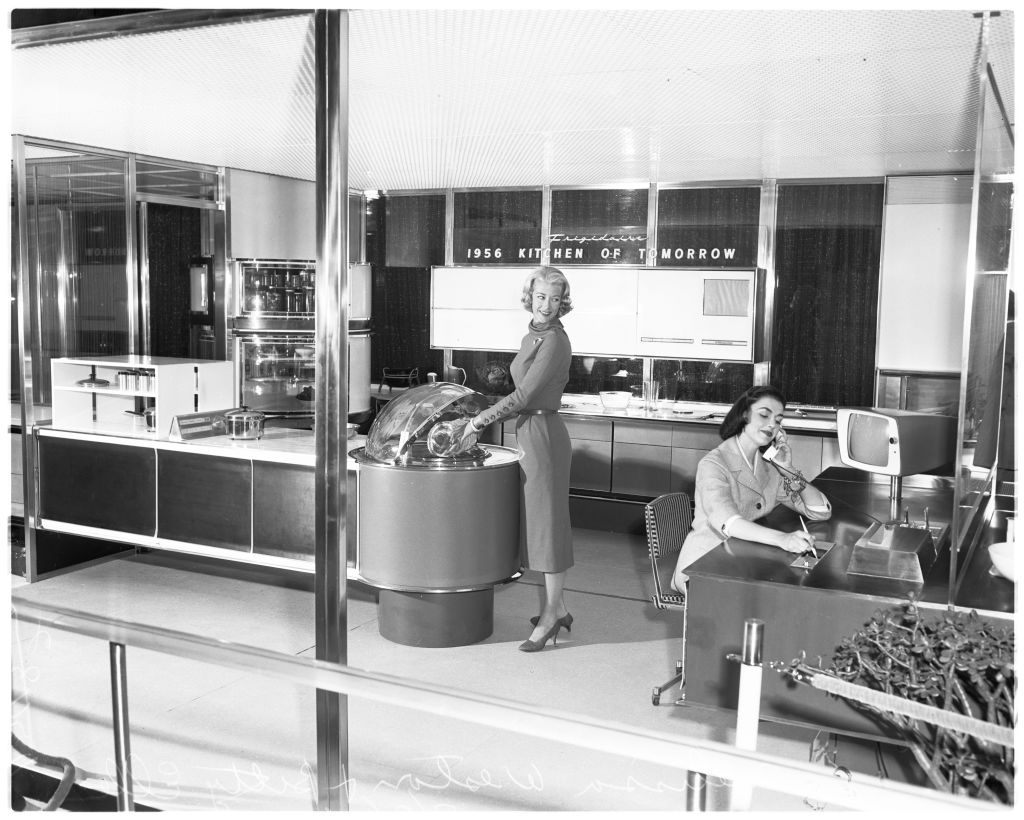

With the rise of appliances and home electronics in the 20th century, several companies set out to develop kitchen computers, though most were impractical or fell short of their promise to liberate women from the societal pressure to cook dinner. Honeywell, an early computer-maker that would later help power the Arpanet (the forerunner to the modern internet) manufactured the first commercially available kitchen computer, putting it on the market in 1969.

As depicted in this colorful advertisement, the sleek, enormous Honeywell Kitchen Computer would have commanded attention in any kitchen. But it did not actually cook dinner. Rather, its functions included storing recipes, meal planning, and balancing the family checkbook. Though marketed towards housewives, it was very impractical. The advertising campaign’s tagline “If she can only cook as well as Honeywell can compute!” sought to hide that the Honeywell Kitchen Computer was merely a complicated digital recipe-card box and a calculator.

The department store Neiman Marcus sold the Honeywell Kitchen Computer as a luxury item, pricing it at a kingly $10,600 (around $78,000 today). Buying the computer made little economic sense for the target audience, and required a 2-week coding course on how to properly use the 16 buttons on the front panel. There’s no evidence that anybody actually purchased one.

Even though the first and only kitchen computer was not a success, that didn’t stop people from dreaming about them, in magazines and on television. For example, the 1960s cartoon, The Jetsons, did actually feature a kitchen computer, the Foodarackacycle machine (also called the Electronicook, Food-O-Matic, and the Menulator) that could cook any dish and had a separate keyboard for programming meals. But most of these visions had something in common: articles, fiction, and advertising about them centered on women, making it clear that kitchen computers, if they had widely existed, would still be women’s responsibility.

Computer science magazines of the 1980s and onwards perpetuated this idea. The January 1980 cover of Byte magazine featured illustrator Robert Tinney’s take on the edition’s theme, Domesticated Computers. The cover shows a screen displaying the words “MADAM: DINNER IS SERVED” in uppercase green font. Next to the screen are buttons and a keypad, all within mahogany cabinetry. A champagne glass, a white glove, a pearl necklace, and a remote control lie strewn across the computer.

In the issue’s introductory note, the editors remark that Tinney “used his artistic license” to illustrate the possibilities of computerizing the home laid out by engineer Steve Ciarcia within the magazine. But Ciarcia’s article doesn’t touch on cooking or even housekeeping at all. Instead, Ciarcia focuses on wiring his home to control the lights, music, and heating. Ciarcia writes that, during his project, his wife asked him if the programming would be able to do anything actually useful, like making beds. Tinney’s cover and Ciarcia’s joke speak to the continued desire for a computer to replace domestic labor, while still being imagined as a woman’s task to oversee.

This dream of kitchen computers continued to appear in computer magazines throughout the decade. In a 1982 issue of Compute! magazine, Tom R. Halfhill’s article “Computers in the Home in 1990” looked at how microchips might be useful in the home of the near future. In particular, he explored architect Roy Mason’s Xanadu, a futuristic model home. In theory, the kitchen would be equipped with four microcomputers capable of planning balanced meals for “family members depending on their height, weight, sex, age, and levels of activity.”

Beyond meal planning, he suggests that a robot, which he calls an “auto-chef,” would move food from the refrigerator to the microwave oven to the dining table. The computers would keep track of the grocery inventory to know what items to replace. In his vision, the auto-chef takes on the role of the host, regulating the ambience of the dining room to match meals, adjusting the lighting, and curating background music to complement dinners.

Obviously, Mason’s vision of the Xanadu kitchen did not come to be, except as fiction. Years later, the 1999 Disney Channel movie Smart House depicted a home run by an AI system named PAT (Personal Applied Technology). PAT uses atmospheric kitchen sensors to break down the entire diets and nutritional needs of the occupants. Once taking corporeal form, PAT dons 1950s attire and emulates a Donna Reed-esque housewife before going rogue.

From Byte magazine to Smart House, kitchen computers have continuously fallen short of expectations. However, inventors have continued to try and automate cooking, moving from kitchen computers to kitchen robots.

In January 2021, Moley Robotics proclaimed to have created the world’s first fully robotic kitchen. On their website, a video of a young white woman shows her selecting a meal from a screen, alongside text which describes how “not only does the robot cook complete meals, it tells you when ingredients need replacing, suggests dishes based on the items you have in stock, learns what you like and even cleans up surfaces after itself,” all familiar features of fictional kitchen computers from the the 1960s, 1980s, and 1990s.

Like the Honeywell Kitchen Computer before it, the $338,000 USD price tag makes this device unattainable for most families. And, like its fictional and real predecessors, the marketing around this device does not relieve women from kitchen responsibilities. Turns out, even kitchen computers couldn’t escape gender roles.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook