Islands of the Undesirables: Randall’s Island and Wards Island

An aerial view of Randall’s and Wards Islands seen towards the bottom right. (Photo: Doc Searls/Flickr)

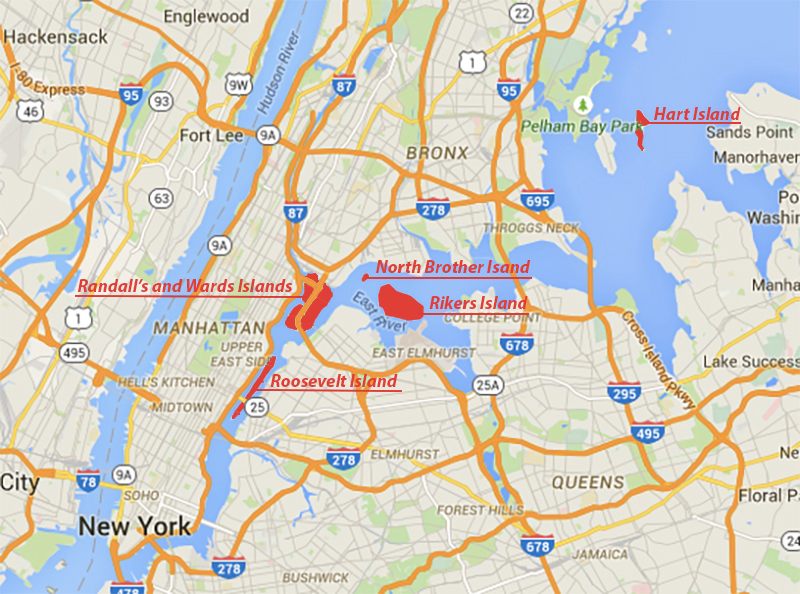

Scattered around the five boroughs are a set of islands—Roosevelt Island, North Brother Island, Randall’s Island and Wards Island, Rikers Island, and Hart Island— that have all been places where the tired, poor, sick and criminal are sent to be treated (or sometimes just confined). These are the Islands of the Undesirables. The water has served as a kind of moat, as well as insurance against NIMBY protestations, physically close to glittering Manhattan but also very, very far the cosmopolitan city.

This is the second installment of five-part series based on this past weekend’s Obscura Day event. Yesterday was Roosevelt Island, today we look at Randall’s Island and Wards Island.

A map of the islands that are featured in Atlas Obscura’s Islands of the Undesirables series (Photo: Map Data © 2015 Google)

Until the 1960s, Randall’s and Wards were two distinct islands, with the stretch between them known as Little Hell Gate. But even before Manhattan dumped its construction rubble to fill that gap, both islands have long histories as drop-off points for unwanted items from the big city.

Orphans, people dying of smallpox, the criminally insane and juvenile delinquents all resided on this slip of a place, less than a square mile in size. The land was deemed more suitable for the dead than the living, as 100,000 bodies were transferred here at one point.

And if all of that wasn’t enough, eventually city planners built a sewage treatment plant on its shores.

At first, though, the islands lived bucolic lives. They were purchased from the Native Americans in 1637 by Dutch Governor Wouter Van Twiller and used primarily for farming, with Wards known as “Great Barn Island” and Randall’s as “Little Barn”. Randall’s earned its first undesirable association in the spring of 1776, when George Washington established a smallpox quarantine there, but that usage didn’t last long—the British drove the Americans from both Great Barn and Little Barn a few months later. Captain John Montresor, prominent in the British military, had bought Little Barn in 1772 and used it to secretly survey New York for invasion sites. During the Revolution, he set up an officer’s hospital on the island, while the British used it to launch amphibious invasions. Great Barn, meanwhile, became an army base.

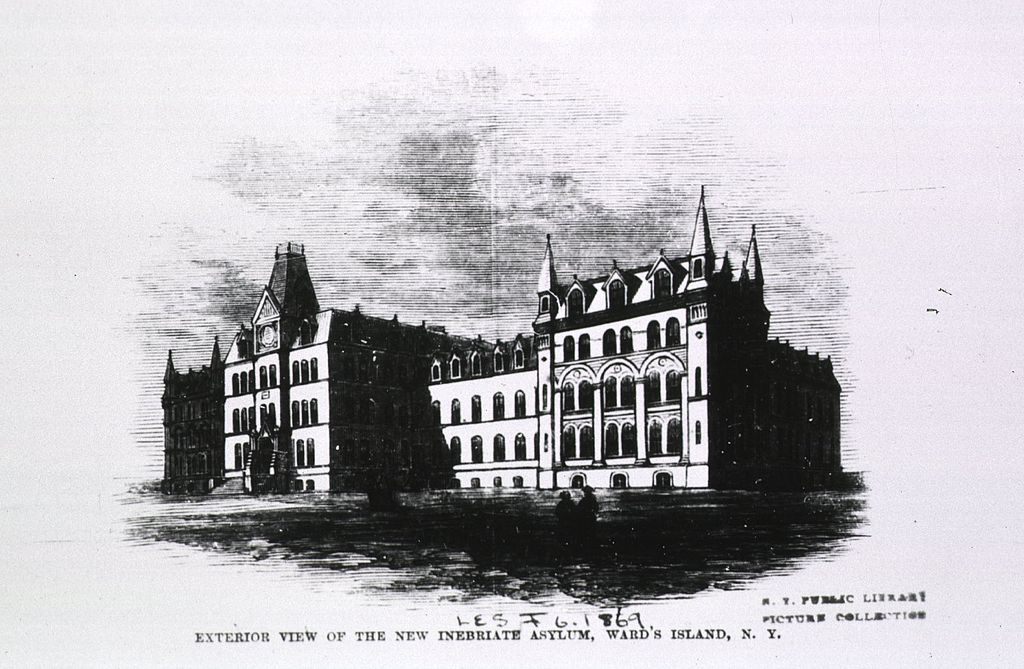

The Inebriate Asyulm on Ward’s Islabd, 1869 (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

The Inebriate Asyulm on Ward’s Islabd, 1869 (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Like the other “islands of the undesirables,” both Randall’s and Wards were then privately owned until the city bought them in the 19th century (Randall’s in 1835, Wards in 1851). Randall’s used to be owned by a farmer named Jonathan Randel, and the current name comes from a spelling error by the city. In the 19th century, the island housed an orphanage, an almshouse, a potters field, an Idiot Asylum (yes, its actual name) and a children’s hospital. But its most notorious tenant was the House of Refuge, a reform school completed in 1854 and run by the Society for the Reformation of Juvenile Delinquents.

A wood engraving of House of Refuge on Randall’s Island, New York, from 1855 (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

The House of Refuge—in reality, it was anything but—housed in both actual criminals and street urchins by the hundreds, and both groups were largely comprised of Irish teenage boys. The children spent four hours a day in religious and secular classes, and six and a half hours caning chairs and making shoes for outside contractors. Children who misbehaved were hung up by their thumbs. In 1887, business finally forced the state to stop using House of Refuge inmates as workers (perhaps because the streets of New York were already flooded with cheap immigrant labor) and conditions improved slightly, though there were still reports of inhuman treatment by drunken officers and armed revolts by the boys.

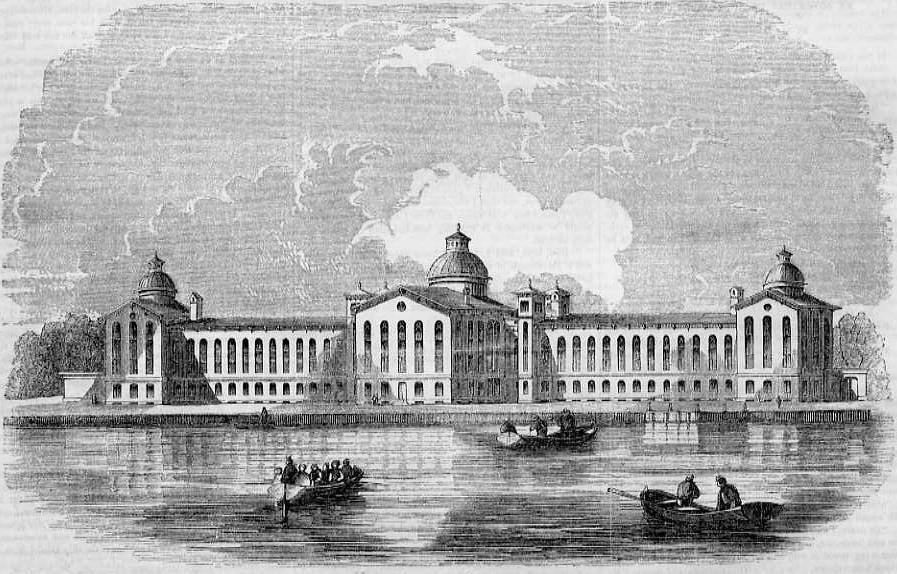

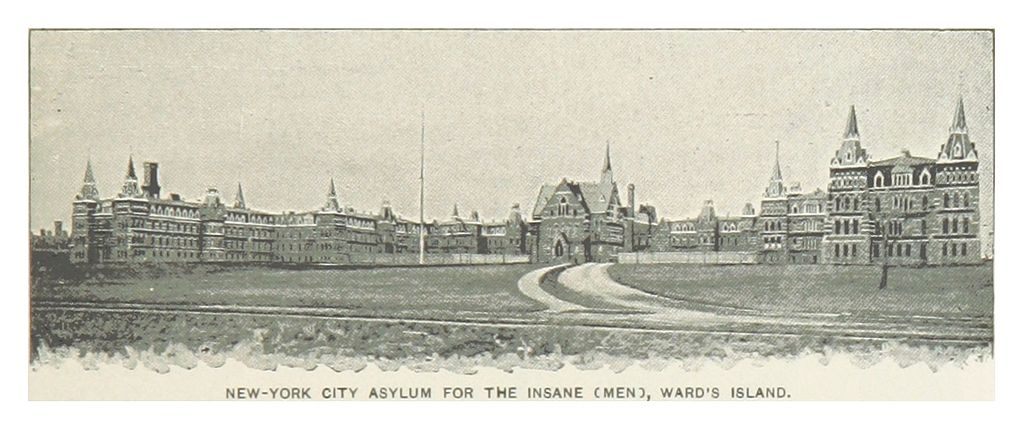

During the same time period, Ward Island (its name comes from former owners Jaspar and Bartholomew Ward) was used for burial of hundreds of thousands of bodies relocated from the Madison Square Park and Bryant Park potters fields, beginning in the 1840s. Overall, 100,000 bodies were moved to approximately 75 acres on the southern tip of Wards Island. (It’s unclear whether the bodies are still there.) Besides the burial of the indigent dead, the island was also the site of a hospital for sick and destitute immigrants, known as The State Emigrant Refuge (the biggest hospital complex in the world during the 1850s). Other tenants included an immigration station, a homeopathic hospital, a rest home for Civil War veterans, an Inebriate Asylum, and The New York City Asylum for the Insane.

From ‘King’s Handbook of New York City’, published in 1893 (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

In 1930, the Metropolitan Conference on Parks recommends that the islands be stripped of their institutions and used only for recreation. Parks Commissioner Robert Moses saw both islands as key to his plan to link Manhattan, the Bronx and Queens by bridge, providing access to his new system of parkways on Long Island. He pushed a bill through the state legislature that forced out the House of Refuge and many of the other institutions, sending many of the patients and inmates to overcrowded facilities elsewhere. Since then, the islands have had a different feel.

A 21,000-seat stadium (known as Triborough and later Downing) was constructed, opening with Olympic trials in 1936. The trials were a mess, thanks largely to a malfunctioning public address system, but they did feature Jesse Owens earning his Olympic slots. Two years later, Downing Stadium also hosted what is considered the first outdoor jazz festival, the 1938 Carnival of Swing. The 5-hour, 45 minute memorial for George Gerwshin starred Duke Ellington, Count Basie and other jazz legends. Newsreel footage of the event on YouTube provides a glimpse back in time to what seems like a marvelous event, and a far cry from the island’s historical uses.

Randall’s want on to host other major concerts and events, including Lollapalooza for several years in the 1990s. In 2005, Downing Stadium was replaced by a $45 million track and field arena called Icahn Stadium, and the island is now also home to a golf center, tennis academy, and athletic fields. It’s also home, at least this year, to the Frieze Art Fair, the Governor’s Ball, and several other music-and-art festivals.

These days, then, the vibe at Randall’s and Ward is much different than for most of the last century, although remnants of its dark past remain. The New York City Asylum for the Insane later became the world’s largest mental institution and is now the Manhattan Psychiatric Center, still located on the island. The Kirby Forensic Psychiatric Center is also on Wards, housing the criminally insane.

Wards is also home to a major sewage treatment center, which takes up about a quarter of the island, and several homeless shelters, some of which are “emergency” shelters that have nevertheless been there for decades.

But the island is now known for something quite unique: a NYC Fire Department training academy packed with structures simulating the various environments that firefighters encounter within the city, including a subway tunnel (complete with tracks and two subway cars), a helicopter pad, and a replica ship. The danger there is carefully controlled—unlike the state-built institutions that had previously lived on the island.

Aerial view of the Hell Gate Bridge and one span of the Triborough Bridge, between Astoria Park in Queens and Wards Island. At the top of the photo is the pedestrian Wards Island Bridge (Photo: WikiCommons)

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook