How Millions Of Secret Silk Maps Helped POWs Escape Their Captors in WWII

The ingenious maps played a role in some 750 successful escapes.

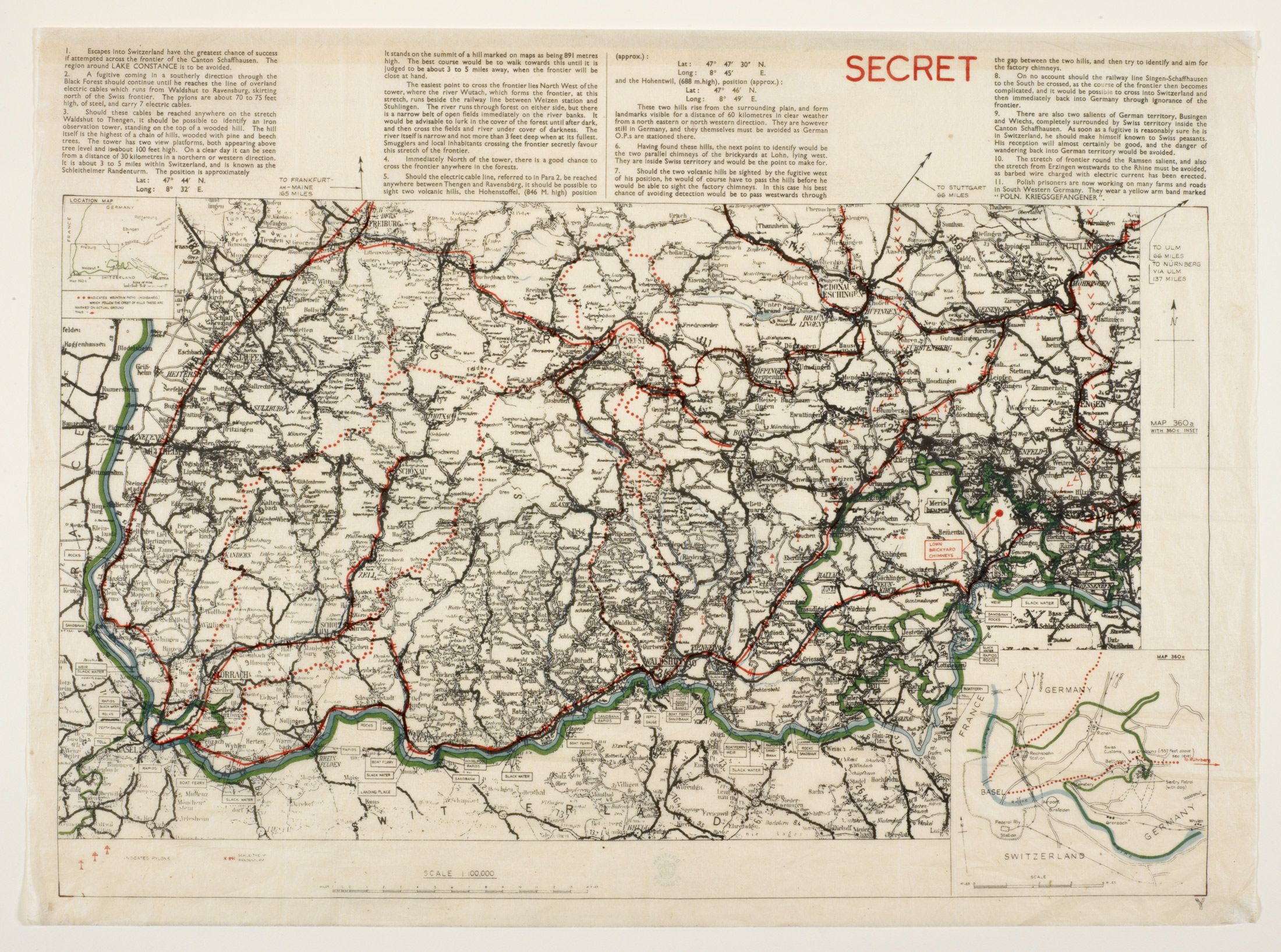

Imagine it’s 1942, and you’re a member of Britain’s Royal Air Force. In a skirmish above Germany, your plane was shot out of the sky, and since then you’ve been hunkered down in a Prisoner of War camp. Your officers have told you it’s your duty to escape as soon as you can, but you can’t quite figure out how—you’ve got no tools and no spare rations, and you don’t even know where you are.

One day, though, you’re playing Monopoly with your fellow prisoners when you notice a strange seam in the board. You pry it open—and find a secret compartment with a file inside. In other compartments, other surprises: a compass, a wire saw, and a map, printed on luxurious, easily foldable silk and showing you exactly where you are, and where safety is. You’ve received a package from Christopher Clayton Hutton—which means you’re set to go.

Hutton—“Clutty” to his friends—was not a typical intelligence officer, moving up the ranks in a predetermined fashion. He had followed his interests rather than any set career path, working as a journalist, a film marketer, and a pilot in the Royal Flying Corps. When war broke out, and he decided he wanted to join up again, he sent dozens of letters and telegrams to various branches of the War Office—all worded, he later wrote, such that “they could not possibly be pushed into a ‘Pending’ tray and discreetly forgotten.”

His gambit was successful. Finally called in for an interview, Hutton told the top brass about how, as a young boy, he had dared a touring Harry Houdini to forego his standard props and escape from a brand new box, constructed in front of a live audience. (Houdini accepted the challenge—and escaped anyway, by bribing the box’s onstage carpenter to use trick nails.)

In the end, it was this anecdote that convinced the head of MI9, Major Norman Crockatt, to hire him. “Old ideas are no good at all,” Crockatt apparently told the 44-year-old polymath. “We want new ones.”

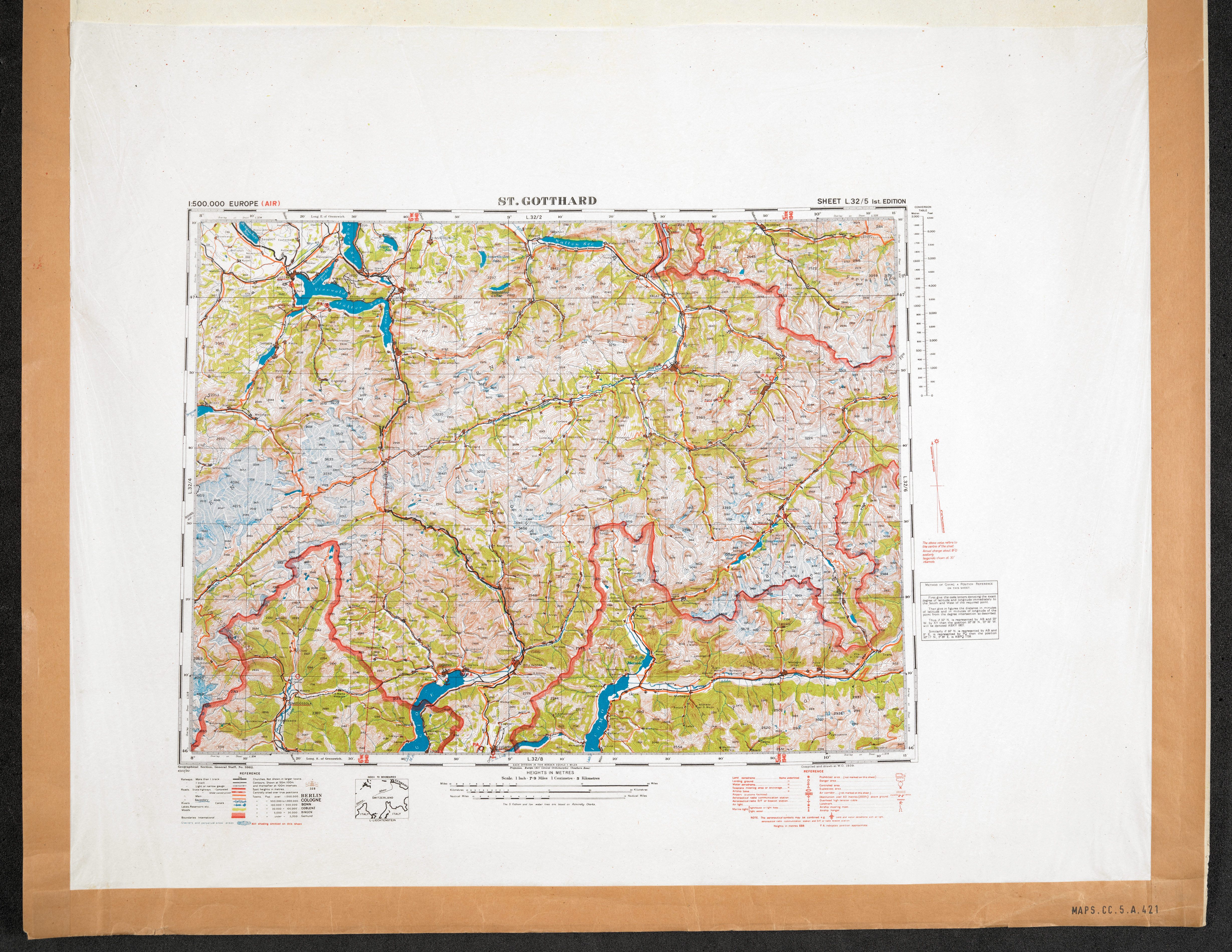

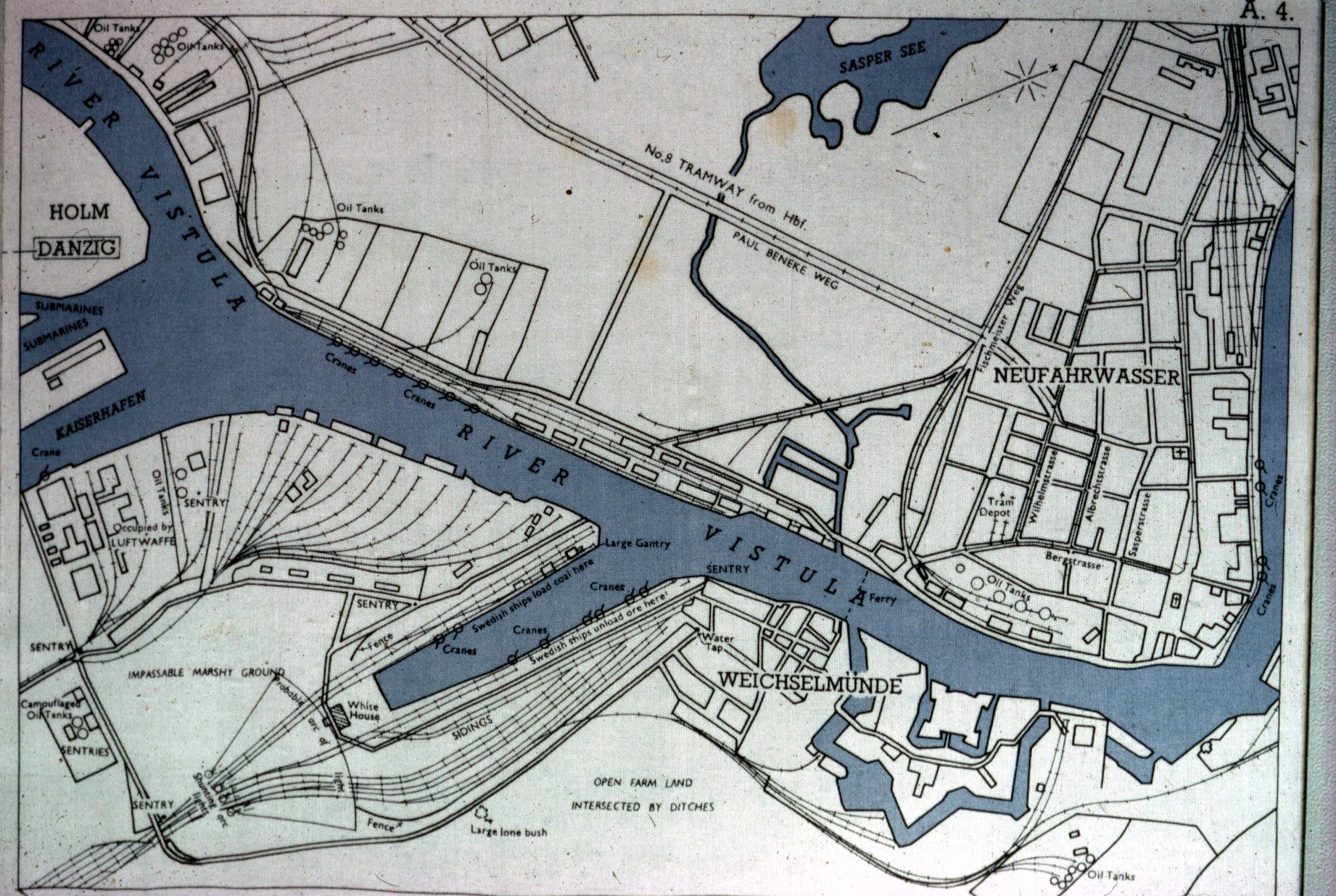

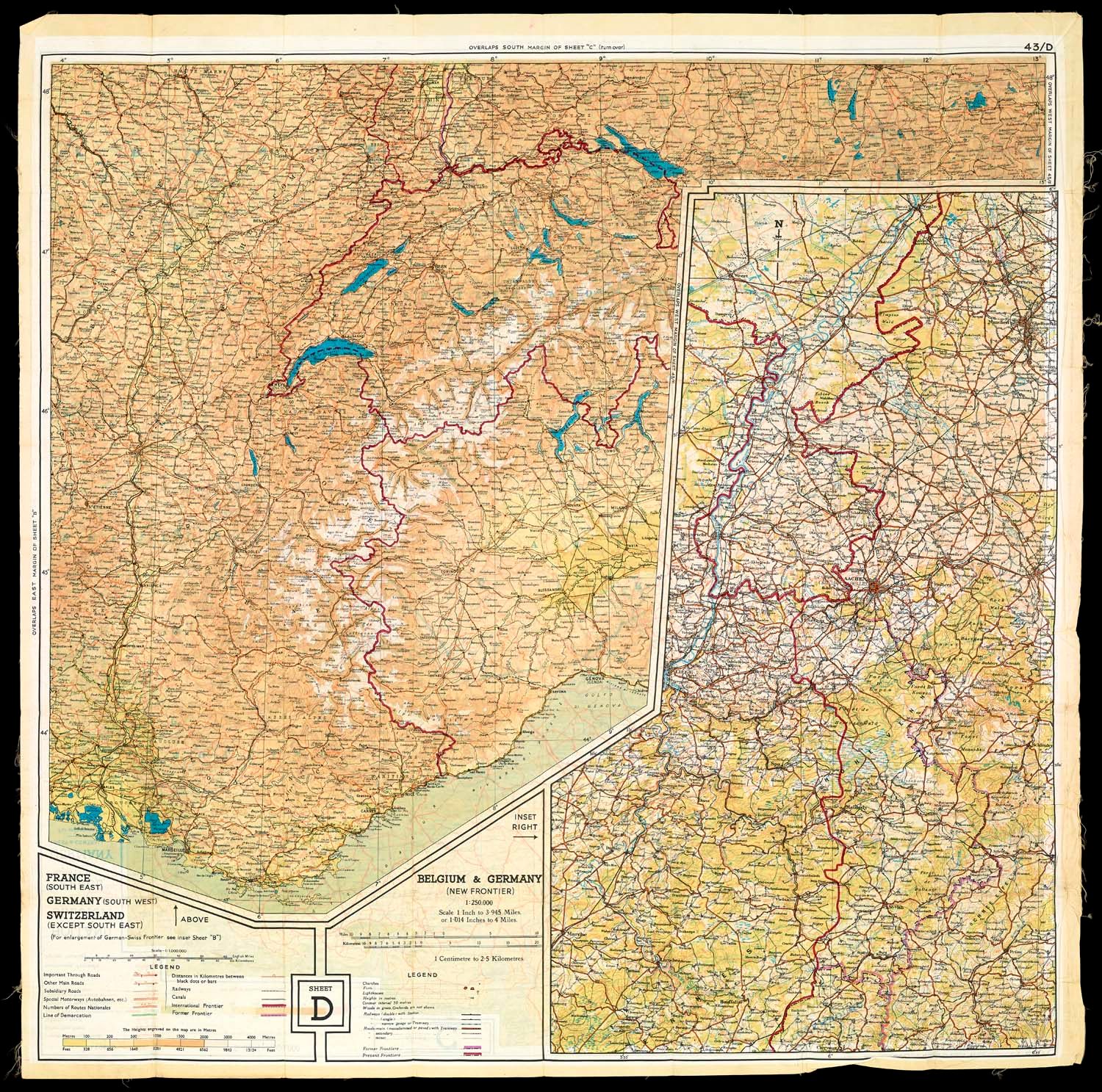

Hutton went straight to work. Over his six-year tenure as Technical Officer to the Escape Department, he would invent dozens of vital gizmos: ration packs squirreled into cigar boxes, miniature compasses hidden in buttons and cuff links, cigarette holders that doubled as tiny telescopes. But his first order of business was maps. In particular, he wanted to create maps to be included in “escape kits.”

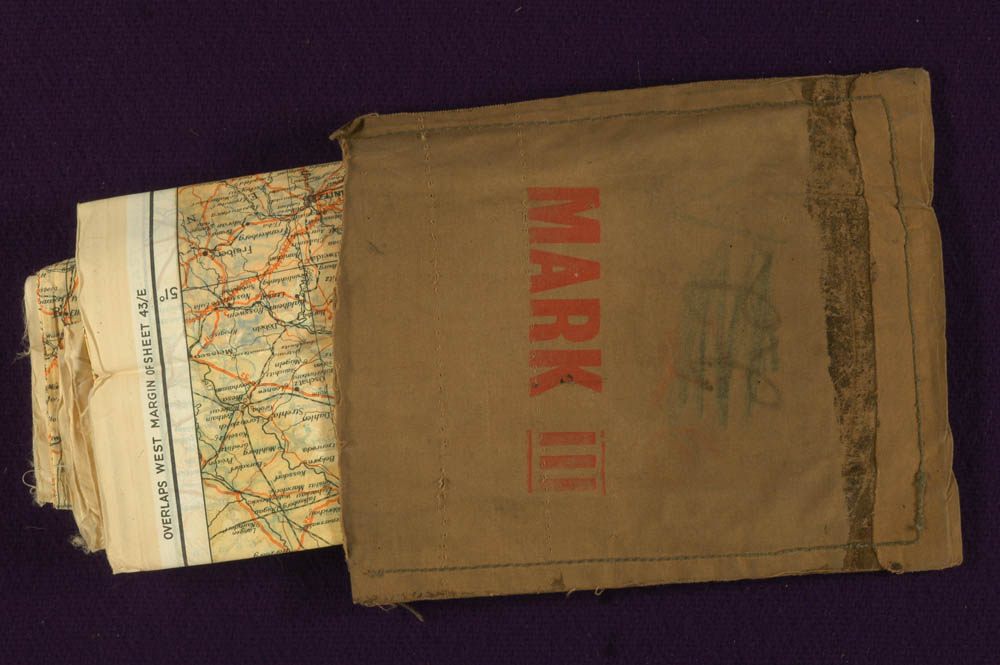

These maps would need to be thin enough to be snuck into a boot or coat lining, durable enough to survive wear and tear in the field—but detailed enough that escaping soldiers could use them to find their way through unfamiliar terrain.

Today, someone seeking accurate views of the world could turn to any number of satellite maps. But such amenities weren’t available in 1939. According to his autobiography, Official Secret, Hutton began his map quest by charging directly into the War Office’s Map Room—whereupon the major on duty gently told him that the British military did not own any maps of Germany at a scale that would be useful to escapees.

In the end, Hutton had to fly to Edinburgh, where he met up with mapmaker John Bartholomew, a decorated World War I veteran who was happy to aid the cause. He gave Hutton permission to use any and all of his maps, free of charge.

Now he just needed to figure out what to print the maps on. The necessary material had to fit a number of criteria: “It had to be so thin that it would take up next to no room when folded, and at the same time it had to be fairly durable and crease-resisting,” Hutton wrote. It also had to be waterproof, easy to print on, and easy to read—and most importantly, when secreted within a flak jacket or combat boot, it couldn’t rustle and give itself away.

Hutton talked to paper manufacturers across London, but none of their offerings worked out. The heavy papers were far too loud, revealing themselves at the slightest prodding. The thin papers—“no thicker than that of the finest toilet roll,” Hutton wrote—were prone to disintegration. So Hutton turned to another substrate: silk.

After days of messy experimentation with different printing materials and methods, he came up with an ink-and-pectin mixture that sat perfectly on the silk’s surface. Soon, his suppliers were churning out maps by the thousands, with frontiers, demarcation lines, and other vital information clearly marked.

Hutton didn’t stop there. Expecting that the country’s silk supplies might soon be reserved exclusively for parachutes, he kept his eyes open for other useful materials. Eventually, he heard about a boatload of mulberry leaf pulp, en route from Japan. Japanese forces made this pulp into paper, which they then used to craft balloons for aerial bombs, sent via the jet stream to the unsuspecting American West Coast.

Hutton was able to get his hands on the valuable shipment. According to Official Secret, the cargo was brought to Hutton by a War Department friend, Bravada, whose job was to stop jewel money from flowing into Nazi coffers by intercepting diamonds traveling from Germany. Bravada—who does not seem to show up in any other accounts of World War II—apparently operated out of a secret room in an office building, located, Hutton wrote, behind a “huge painting of a reclining nude.”

The same qualities that made the mulberry paper perfect for weaponized balloons also made it ideal for maps. Hutton brought it to a group of paper scientists, who got to work. “I jigged about like an excited schoolboy as I watched test after test,” Hutton wrote. “The results were sensational.”

The paper was thin enough to see through, but could hold detailed charts printed in seven different colors. It could be dipped in water, crumpled up, and shoved down into a boot—and when it was retrieved hours later, it could be smoothed out with nary a rustle.

Hutton’s next challenge was figuring out how the silk and mulberry leaf maps could be carried in a clandestine way. For soldiers not yet deployed, Hutton did as much as he could with flight boots: a silk map and compass were stuffed into cavity in the heel, a small knife was tucked into the cloth loop, and a long, thin wire saw was threaded into the laces. An escaping fighter could use the knife or saw to cut the boots’ tops off, transforming them into much less conspicuous “civilian shoes.”

But the fighters who needed the maps most—those who had already been captured—were trickier to access. Hutton came up with a plan for that, too. Thanks to the Geneva Convention, prisoners of war were allowed to receive packages from their families and other aid organizations. Parcels that contained games, sports equipment, and other fun pursuits were especially encouraged—not only by the POWs themselves, but by their captors, who figured hobbies would keep bored prisoners out of trouble.

“These voluntary gifts, designed for the comfort and entertainment of the prisoners, were flooding the camps from hundreds of sources,” Hutton wrote. “There was no valid reason why we should not take cover behind this multiplicity of well-wishers.”

Hutton and his team went to work setting up a number of fake organizations, each with their own letterhead, slogan, and address (often that of a recently blitzed building). The “Prisoner’s Leisure Hours Fund” got scores of books past the German censors, who were too focused on the stories’ content to notice the maps and hacksaw blades stuffed inside their covers. If a table tennis kit came in from the “Licensed Victualers Sports Association,” prisoners would look for contraband maps and compasses secreted within the paddles.

Hutton laid intelligence groundwork to alert captured soldiers of these options: most of the prison camps eventually had “escape committees,” made up of the few soldiers from every squadron who Hutton had let in on his methods and taught to communicate in code. A month into what Hutton was calling Operation Post-Box, the rate of attempted escapes by British POWs had more than tripled.

As guards and censors cottoned onto his methods, Hutton became more ingenious. He hid maps inside gramophone records (as recipients would break the records open to get at the maps, Hutton called this “Operation Smash-Hit”). He cut a country’s map up into 52 squares, took a pack of playing cards, and hid one square inside each card (the Joker held the map key). He stuck maps into each side of a wooden chessbox, and a small wireless set inside the base of the king.

But the enemy, of course, wasn’t stupid. “By the end of the war, the German security experts must have been in possession of the full story of my inventions,” wrote Hutton. There was only one trick they never figured out: the clandestine Monopoly boards.

As Erin McCarthy details in Mental Floss, the company that printed Hutton’s silk maps for him, John Waddington Ltd., also manufactured all of the country’s Monopoly boards. After Hutton approached them, the Waddingtons set up a secret room in their factory, where a select cadre of employees rejiggered the game boards—punching small compartments into them, hiding the tiny tools, and covering the hole with a game space decal.

“When their job was done,” McCarthy writes, “the board was indistinguishable from one a regular citizen might buy in a store.” No one who wasn’t directly involved knew about this trick until the relevant documents were declassified in 1985.

Hutton’s gadgets eventually numbered in the dozens—and they were so nifty, he wrote, that his most aggravating security risk was when people who visited his offices pocketed them to show their friends. Hutton shared many of his creations with America’s Escape and Evasion Section, which duly began printing maps on rayon and carving up Monopoly boards. All told, the British and American military produced 3.5 million silk and rayon maps.

By the end of the war, expert Philip E. Orbanes says, 744 captured airmen had freed themselves using tools designed by Hutton. Thousands more who escaped without tools, or were shot down and evaded capture, may have benefited greatly from MI9’s overall philosophy of “escape-mindedness.”

In the aftermath of the war, many of Hutton’s secrets were publicized by German and British newspapers. The silk maps were declassified, and leftovers went on sale across Europe, as the same demureness and foldability that made them great escape aids made them even better scarves and handkerchiefs.

These days, the maps are a rare collectible, suggesting that many soldiers hung onto theirs as souvenirs. This makes a certain amount of sense. Soldiers may eventually get rid of uniforms. But who wouldn’t want to keep the bit of silk that came to you in a game box, folded up small, and—with nary a rustle—showed you how to make it back home?

“In 1949, in a French antique shop, I bought one,” Hutton wrote. “It cost me four pounds”—a 2,000 percent markup.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook