Ancient Greek Funerals Were Decked Out in Celery

It was a powerful symbol of death—and victory.

When it comes to leaving flowers on a grave, lilies or roses are a common choice. Sometimes, they’re fashioned into a hoop: a funeral wreath. Such wreaths date back thousands of years. Ancient Greeks used vegetation to honor both victories and the fallen dead. Today, their Olympic olive wreaths are still familiar. But we no longer see a once-common arrangement: In ancient Greece, the most potent way to show love for the fallen was with a wreath of celery.

Back then, it was a very different celery. Native to the Mediterranean and Middle East, wild celery has thin stalks and a bitter flavor. It was only later that farmers bred celery to have sturdy ribs and a sweeter profile. Its strong smell and dark color struck ancient Greeks as positively chthonic: that is, associated with the Underworld and death.

As a result, celery became an essential part of burials. In ancient Greece, celery covered graves, and the dead were often crowned with it. We know this, writes classicist Robert Garland, because the first-century Greek writer Plutarch referred to celery as the most common plant used for the purpose. Historians have floated various theories as to why the dead needed to be garlanded. Perhaps they had faced life with courage, and deserved to be buried as heroes. Garland rejects this in favor of another theory: that the dead were given heroic crowns “to add dignity and lustre to the proceedings.” Other writers, such as the Roman Pliny the Elder, considered celery off-limits as an everyday food, since it was prominent at funeral banquets.

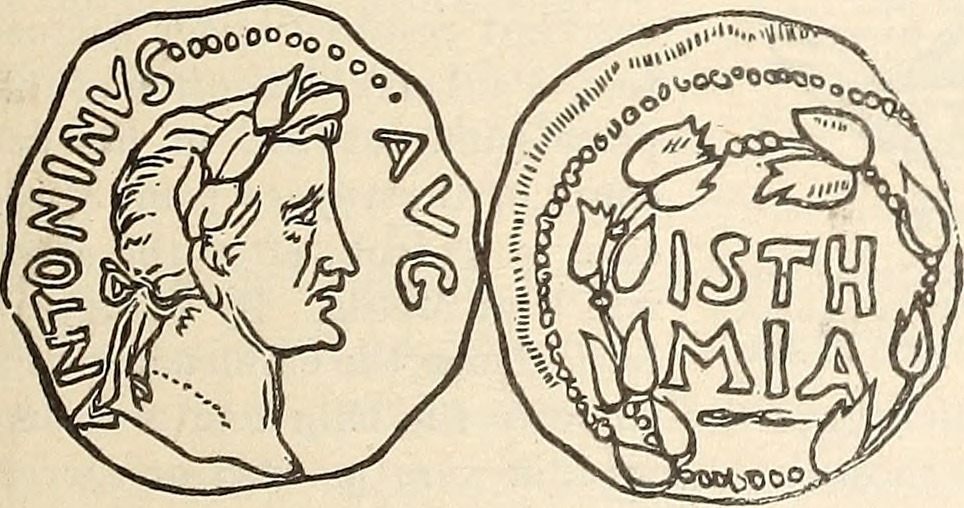

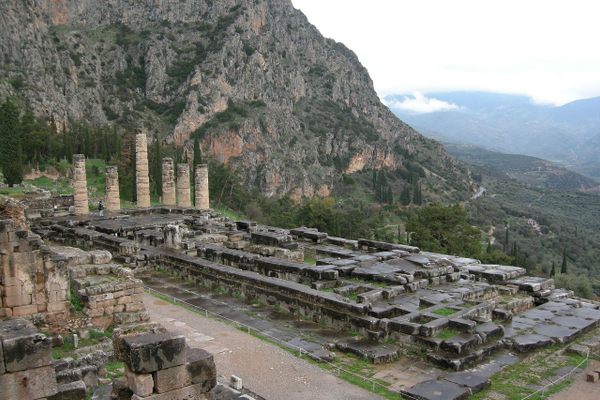

The association of celery with death even entered the lexicon. The phrase deisthai selinon, or “to need celery,” didn’t mean that the subject needed to eat more vegetables. It meant someone was close to death. “The connection between celery and the dead is a recurrent one in Greek thought,” writes classicist Corinne Ondine Pach. At the Nemean and Isthmian games, both associated with death, winners were awarded crowns of celery.

Celery, then, had a strange dual meaning. One plant encyclopedia calls it “a double symbolism of death and victory,” one that reverberated throughout the ages. Celery and parsley, both in the Apiaceae family, were often mistaken for each other in ancient writings, to the point of interchangeability. As a result, both plants were long considered able to ward off evil spirits in Europe, and parsley maintained a dark reputation. Once dedicated to Persephone, Queen of the Underworld, grumpy farmers later claimed that slow-germinating parsley seeds needed to visit the devil nine times before they deigned to grow.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook