The Historic Treaty That Ended Navajo Imprisonment Has Been Returned

One of just two copies thought to survive is back in Navajo Nation.

In 1868, the Navajo signed a treaty with the U.S. government that ended several years of imprisonment and gave them the right to return to their homeland in the Four Corners region, where Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, and Colorado meet. Three copies of this treaty are thought to have existed. One was placed on file with the National Archives, where it remains to this day. Another was given to Barboncito, the last Navajo chief to surrender to military forces in 1866, and one of the signatories. Historians assume it was buried with him after he died in 1871. The third and final one—known as the “Tappan copy,” named for Indian Peace Commission member Colonel Samuel F. Tappan, who helped negotiate the pivotal treaty—had been missing for a century.

Tappan’s great-grandniece, C.P. “Kitty” Weaver, and her family discovered the well-preserved document in the attic of his Manchester, Massachusetts, home in the 1970s. But it wasn’t until last year’s 150th anniversary of the treaty’s signing—which Weaver attended, with the treaty—that she became aware what the document truly meant to the Navajo people, she told the Navajo Times. Weaver has since donated the treaty to the Navajo Nation. According to Navajo Nation Museum director Manuelito Wheeler, the acquisition of the original document is remarkable. “I’ve asked around, even asked the National Archives, and I can’t find a single other tribe that has their treaty … which is kind of interesting,” he told the Times.

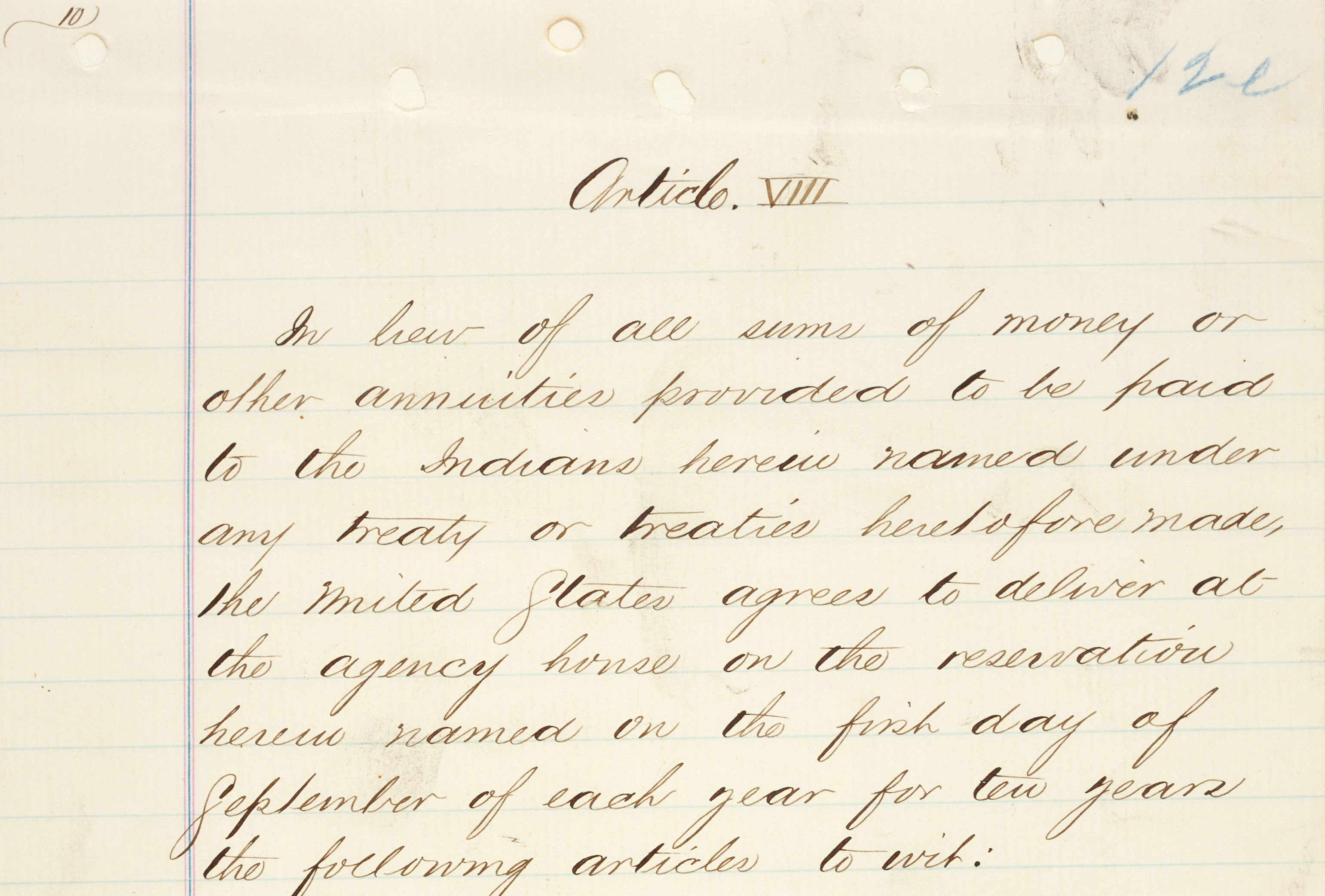

The rare document will be on display at the museum, in Window Rock, Arizona, through June 7, 2019, for the 151st anniversary of its signing. The copy is roughly 13 pages—shorter than the version housed in the National Archives—which indicates that the Tappan copy is abridged, according to associate registrar at the museum, Ben Sorrell. “It has all the same stuff in it, but the language is shortened,” he told the Times. It is now believed that this was likely Tappan’s personal copy of an early draft.

The 1868 treaty came after a long history of the U.S. government’s displacement of the Navajo (among many other indignities, injustices, and worse visited upon Native Americans). In 1863, the military destroyed the Navajo crops and livestock, and pushed them out of their native land. They were forcibly moved—an event known as the Long Walk—to the Bosque Redondo (which the Navajo called Hwéeldi) at Fort Sumner, New Mexico, where they were imprisoned for five years. Tappan and General William T. Sherman hoped to move the Navajo people to Kansas and Oklahoma, but the Navajos rallied for their Four Corners home. The successful return to this sacred, mountainous homeland was rare among the fates of Native American groups, and the treaty signifies the end of the Navajo Nation’s imprisonment.

Per an agreement between Weaver and the Navajo people, the Tappan copy must be housed in a climate-controlled box, and it cannot be sold or displayed for more than six months over the next 10 years. Today, the Navajo reservation is 27,000 square miles—the United States’ largest.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook