The Art of Hand-Carving Headstones Isn’t Dead Yet

Meet the new generation of artisans keeping the tradition alive in U.S. cemeteries.

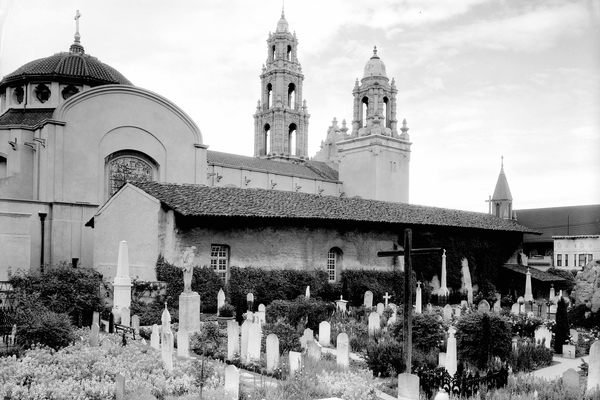

In Portland, Maine’s Eastern Cemetery, tall grasses tilt in the breeze among the winged death’s heads. Across the gently undulating landscape, granite and slate tablets inscribed with names and dates, weeping willows and decorative urns mark the final resting place of some 4,000, most interred between 1668 and 1930. Intricate designs and mismatched letters, some sharp and bold, others faded nearly to illegibility, tell the stories of the past in beautiful, hand-carved relief.

Just down the road at the Forest City Cemetery, opened in 1958, the view is very different. Here, sandblasted and laser-etched headstones form uniform rows. The words on each stone are clear, and the lettering on each is almost identical, lacking the unique flourishes of older markers. The first technology to produce gravestones en masse by machine was developed in the aftermath of the Civil War, a necessary efficiency when memorializing hundreds of thousands of fallen soldiers. The innovation also made it cheaper to memorialize the resting places of loved ones. These modern memorials grew in popularity in the United States until, by the mid-1900s, the art of hand carving seemed ready for its own burial beneath a machined headstone.

Still, a few stalwart souls continue to practice this old art. Today, by most industry estimates, 20 shops in the United States specialize in headstone carving. Among those shaping the future of this anachronistic sector are millennial and Gen Z carvers, some continuing family traditions and others starting new firms.

Sigrid Coffin, 38, is a second-generation carver who has always had a deep love of lettering, like her mother, who has a passion for painting and calligraphy. “I love the process of putting a letter into three dimensions,” she says of the art form she finds so satisfying. “It doesn’t feel old-fashioned when I’m doing it,” she adds. Sigrid Coffin is one half of Coffin & Daughter, where she works alongside her father, Douglas Coffin, who has been doing this work as long as Sigrid has been alive. Their studio is just a few hours away from Portland in Belfast, Maine, in a region where many of the country’s carvers are still based because of the trade’s colonial history and New England’s abundance of stone.

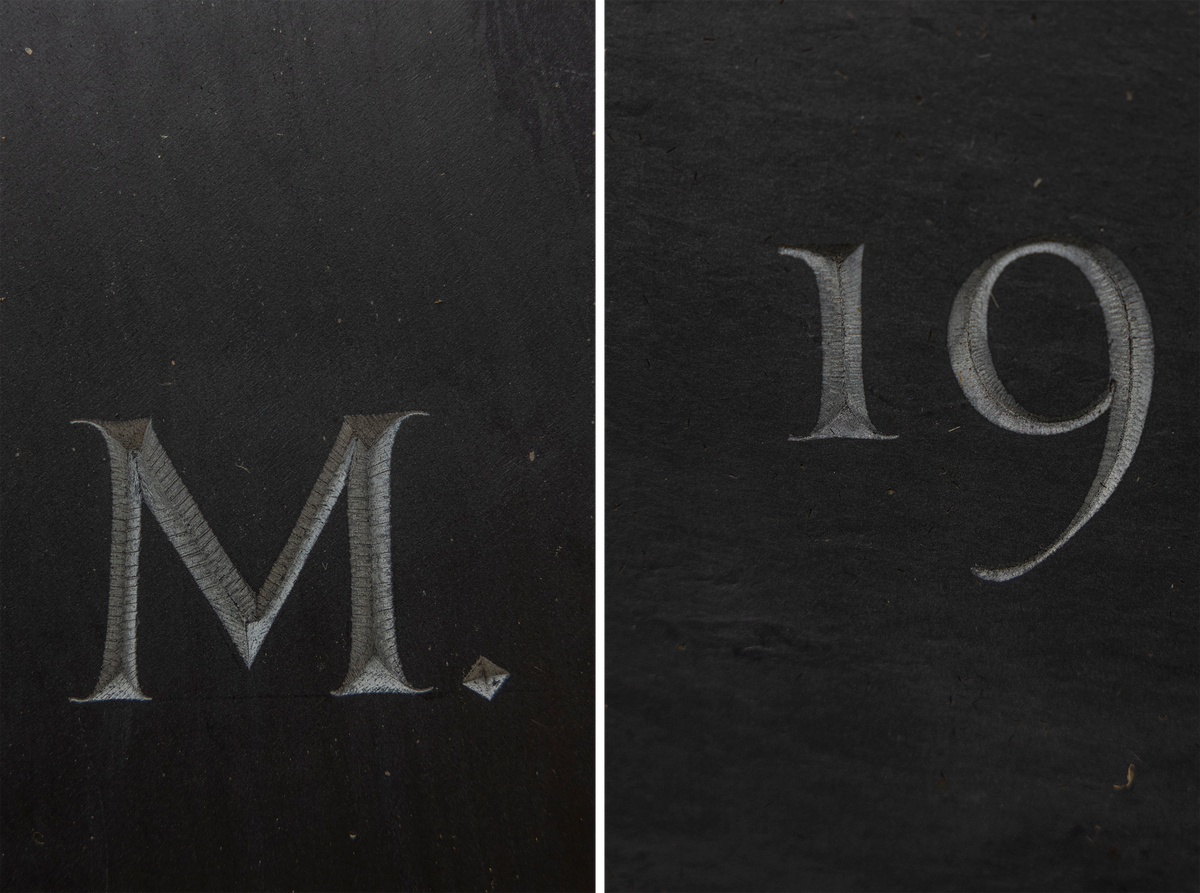

Inside the studio, small slate tiles lay scattered around the room. A neatly organized shelf is lined with color-coded chisels—green for granite, blue for slate—and a half-dozen headstones in various stages of completion await finishing touches. A work in progress rests on a purpose-built easel and Coffin, who joined her father in the business 11 years ago after studying bookbinding and calligraphy, wields her chisel and mallet, rolling the tool back and forth, working up one side of the L she is carving and then the other to create perfectly symmetrical grooves.

It’s difficult and delicate work, but it is work with meaning and purpose. “It’s very powerful to see your loved one’s name in stone,” Coffin says. “There’s something about the permanence that adds to the gravity.” While modern, machine-made headstones can also offer a family solace, she says, there’s something special about helping someone in mourning design such a personal and lasting memorial to a loved one and then putting the time and effort into creating it with her own two hands. “I feel like I have a connection with them,” Coffin says.

But carving letters, especially, is unforgiving, and the process is neither fast nor cheap, often requiring 70 hours or more from concept to completion. At Coffin & Daughter, that means an average of 15 to 20 headstones are completed each year. One headstone can cost between $500 and $20,000 and might require one of the Coffins to travel across the state or across the country to install it; their work can be found in cemeteries from Maine to California and Florida to Prince Edward Island. No two customers—or headstones—are the same, though those who chose a hand-carved stone are often of a similar ilk, among them poets, boat builders, and fellow lovers of letters. “People who appreciate the beautiful, something handmade,” Coffin says.

“People’s connection to the physical world—that is to say, working with one’s hands and understanding the materials with which one work—has fallen away, and with that loss of skilled craft is the loss of context for understanding well-made things,” says Nicholas Benson, owner of the John Stevens Shop in Rhode Island, one of the oldest continuously operating stone carving business in the U.S. It first opened in 1705, and Benson’s grandfather took over in 1927, followed by his father and himself in 1993. Now, he worries the craft is dying, and that his daughter, Hope, may be fighting a losing battle if she decides to take on the family business.

At 22, Hope Benson is the youngest carver she knows of in the trade. A love for the Old World aesthetic and the long lineage of carvers in her family pulled her in, as did an appreciation for the mystical. (Her mother is a professional medium) But she is not yet certain if she will pursue a career in carving or chart her own course in some other industry. Benson is still learning and exploring her individual style; hers is one that favors more traditional emblems while her father is renowned for more modern, refined lines. “I love colonial cemeteries. Everything about it. The ambiance, history, vibe, esthetic. If I were to find passion in this field it would be for the old stuff,” Benson says, but adds, “I wouldn’t want to undermine anything my father, grandfather or great grandfather have built. But I want to do my own thing.”

Tracy Mahaffey, a carver based in Rhode Island, didn’t grow up in a family of carvers. She learned via a non-familial apprenticeship. Fellow Rhode Island carver Karin Sprague invited her into her workshop decades ago and now Mahaffey teaches the craft herself. “Teaching is necessary to keep his craft alive,” Mahaffey says. So, she does just that throughout North America and in Europe, where the community of hand-carvers is much larger. In the UK, schools teach stone carving, and the tradition is alive and well among scores of carvers who etch memorials in stone, from headstones to plaques memorializing visits from the queen.

In the United States, carving may not be a growing profession, but “as long as there are people who are passionate about lettering and this Old World craft, it will be around,” Hope Benson says. “It is a very niche thing.” Coffin adds. “People who are drawn to it get why, so the craft is self-selecting.” Meaning there will always be people like herself who understand the craft’s importance and artistry, and appreciate the technique present in every chisel strike and the meaning imparted to the finished product by the time and skill of the artist.

That’s a heartening sentiment for anyone who has wandered a cemetery at dusk, reading fading inscriptions, feeling the indentations and flourishes, the result of chisels tapping the soft stone, and admiring the calligraphy and artful renderings of flowering vines or winged cherubs. Or in Coffin’s case, an artfully rendered Scotch thistle on a tall, thin, quintessentially shaped gravestone in Seaview Cemetery in Rockport, Maine that marks the final resting place of a husband and wife. The black slate stands out strikingly among the wide, flat, modern granite that’s installed nearby, but at the same time, seems to belong among the mishmash of old and new that epitomizes New England cemeteries. It’s proof that even though the ages-old tradition of hand-carving headstones may no longer be the standard, and though a modern culture strains to understand it, the craft is alive and well amongst the dead.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook