Understanding the Majesty and Complexity of Great Organs

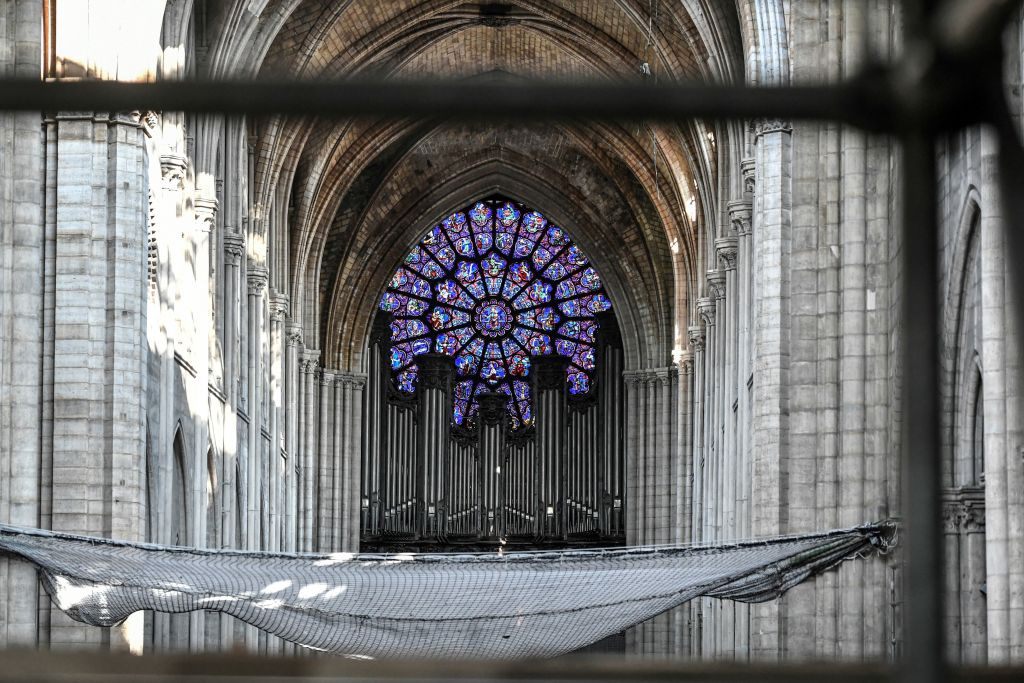

Notre Dame’s famed instrument is being dismantled and restored following the 2019 fire.

In Paris, situated a mile apart, are two giants of musical and architectural magnificence—epic voices that carry the passion, cultural tastes, and sound of their eras into the present day. The pipe organs of Notre Dame and Saint Sulpice have resounded for centuries, so when fire tore through the former in April 2019, some minds turned quickly to the fate of its cherished instrument.

“Two miracles happened that day,” says David Briggs, an international concert organist and composer. “Nobody was killed, and the great organ survived.”

These astounding instruments are splendid symbols of culture and heritage, mourned when they are lost and celebrated when they survive the worst. In 1945, when Allied bombing collapsed the Frauenkirche in Dresden—a German Baroque masterpiece—the organ that Bach himself had played two centuries before disappeared with it. It’s no wonder that restoring or rebuilding these storied instruments can emerge as a top priority, though the process isn’t easy.

Pipe organs are not only one of the most physically complex instruments, they carry deep symbolism and emotional resonance. “An organ is always monumental,” says Bertrand Cattiaux, the organ builder and restorer who has been charged with the care of Notre Dame’s instrument for more than 40 years. “It’s often in a church, so for people it represents moments of joy, of pain, and of prayer; the music of the organ accompanies all these moments.”

In August, the long process of dismantling the Notre Dame organ, overseen by Cattiaux, began, to be followed by cleaning and restoration. Though the instrument was largely spared direct damage from the burning roof and spire that collapsed parts of the cathedral’s vaulted ceiling, it was coated with toxic lead dust, and then suffered from exposure to searing heatwaves and winter’s cold. The restoration is expected to last several years. Removing the nearly 8,000 pipes and many other parts alone will take five months, with three teams working together, says Cattiaux.

To see an organ being dismantled is to watch men work in the belly of a colossal beast. Pipes of wood or metal come out like ribs and must be carefully placed and ordered in containers for storage and transport. At Notre Dame, the largest pipe is 32 feet long (representing the lowest bass note), and the smallest about half the length of a pencil. The organ is essentially based on medieval technology; the earliest incarnations at Notre Dame date as far back as the 14th century, though the current instrument dates to 1733 and has undergone a number of modifications since.

In its most basic form, a pipe organ is a large, sometimes huge, wind instrument operated by keyboard. (It once took six to eight men to manage the bellows that pump air into the pipes at Notre Dame and Saint Sulpice. That function was electrified in the 1920s.) Each of the multiple keyboards corresponds to a section of pipes that together generate a variety of tones and musical color: pure organ sound, the flute family, reed instruments such as oboes, and strings, explains Kent Tritle, the director of cathedral music and organist at New York City’s Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine, and a leading choral conductor. The organ pedals, played with the feet like giant keys, provide the rumbling bass notes.

“It’s like a whole orchestra controlled by one person,” says Briggs, who has performed on organs across Europe and is currently artist-in-residence at St. John the Divine (where a state-of-the art electronic organ is in place while the cathedral’s 110-year-old instrument awaits cleaning, following a fire that occurred a day before Notre Dame’s). “We have an enormous palette of color.”

But the organ itself is just one part of the sonic and aesthetic equation; the other is the architecture that houses it. To hear an organ fully is to experience it in what organists call “the room.” Whether an intimate hall or a vast cathedral, the size, shape, and building materials are vital factors. Organs respond especially well to wood and stone, says Tritle, who oversaw the installation of a new pipe organ at the Church of St. Ignatius Loyola in New York in 1993. Acoustics, of course, is a science unto itself, but even furnishings such as carpets and cushions on pews can impact the quality of sound, he says.

It’s an experience listeners feel as well as hear when an organ unleashes a massive chord that reverberates through a church (and one’s bones) and hangs in the air for several seconds. Size and volume are not necessarily the marks of a great organ, however; it’s the craftsmanship that imparts a distinct musical personality, combined with the way the sound blends and resonates, that distinguish a good organ from a great one, Briggs and Tritle agree.

A key part of an organ’s character derives from a process called voicing, a critical stage in organ-building in which fine adjustments are made to each and every pipe to integrate their sound with the acoustic environment. Cattiaux calls voicing “giving the soul of the instrument,” noting the French word for it, harmoniser, but it is definitely not the same as tuning. “Tuning is tuning,” he says. “Voicing is artistry.”

Though the organs at Saint Sulpice and Notre Dame are both primarily the work of distinguished 19th-century French organ-builder Aristide Cavaillé-Coll, their paths diverged from there. Saint Sulpice’s organ has remained largely intact since its completion in 1862, and it lends itself well to the French Romantic music of that era. It fills the church with exceptional warmth and sonic nuance.

At Notre Dame, music rang boldly across the long nave, and will once again. The organ is “like a musical equivalent of a very distinguished smorgasbord,” says Briggs—the result of the various alterations and renovations that include Cavaillé-Coll’s major work in 1868 and a 1991 overhaul that computerized its systems.

Tritle is keen to note that organs are not only a cornerstone for sacred music; the instrument was influential for many classical composers who also wrote important secular works. Mendelssohn, Handel, Saint-Saëns—even Beethoven and Mozart—played the organ. Bach in particular is closely associated with the instrument. A master organist who composed countless religious works in 18th-century Germany, he was asked to inaugurate the pipe organ designed by renowned German builder Gottfried Silbermann for the original Dresden Frauenkirche in December 1736. (The collapsed church was rebuilt with a new organ of a different style in 2005.)

Despite the numerous overhauls, restorations, and outright rebuilding that historic pipe organs can undergo, their power to rouse and bring communities together has not changed. Just as the organ sound was central to life in medieval times, so the resurrection of Notre Dame’s voice is regarded as central to healing in Paris. The goal is to have its glorious sound back in the cathedral on the fifth anniversary of the fire, in April 2024.

Cattiaux recalls the devastation he and so many others suffered in the wake of the blaze. “But then the first time I went to see the organ,” he says, “there were all these people working to preserve and save the cathedral. There was an extraordinary spirit, and this was energizing. That spirit is still there today.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook