Grasshoppers Are Pink, Lobsters Are Blue, These Off-Color Animals Will Make You Rethink Everything You Knew To Be True

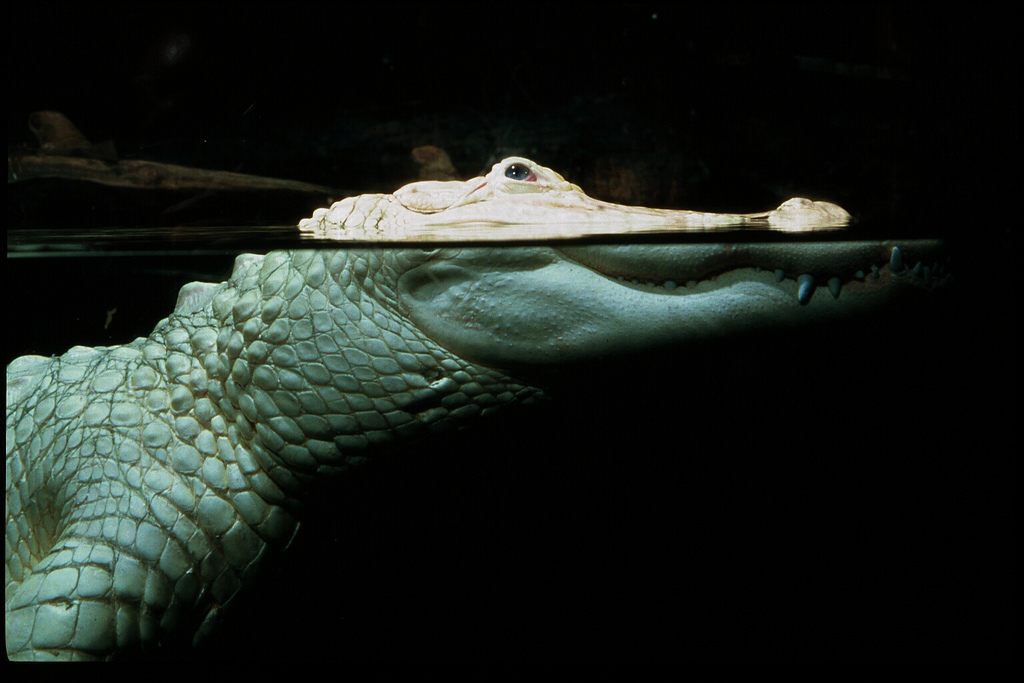

An albino alligator at the California Academy of Sciences. (Photo: Brocken Inaglory/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

An albino alligator at the California Academy of Sciences. (Photo: Brocken Inaglory/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

Grasshoppers are supposed to be green. Or, depending on where they live, brown, grayish or a dull ochre. They’re trying to blend in. They’re not supposed to be pink. But sometimes they are.

So are katydids, which are part of a family sometimes called “long-horned grasshoppers,” even though they are not grasshoppers, but a different sub-order of animal. Even so, they’re usually not pink.

A pink katydid at the Audubon Butterfly Garden and Insectarium. (Photo: Jayme Necaise/flickr)

Early on in life, we’re taught to associate colors with animals. Bears are brown, or else they’re black. Frogs are green, and lizards often are too. Tigers are orange. Lions are tawny yellow. Elephants and rhinoceroses are grey. Flamingos are pink. Grasshoppers and katydids are not.

But sometimes, through a genetic aberration, animals are born a different color. The condition that makes grasshoppers and katydids pink is called erythrism, which essentially just means that they’re redder than they should be. But there’s a whole rainbow of off-color animals, from snow white alligators and pink elephants to bright blue crabs and lobsters, birds split into green and blue halves, and jet black guinea pigs.

An albino elephant at Kruger National Park, South Africa. (Photo: Yathin S Krishnappa/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

An albino elephant at Kruger National Park, South Africa. (Photo: Yathin S Krishnappa/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

Albinism is perhaps the best understood aberration, although there’s not one genetic mechanism that robs creatures of their melanin. But there are albino squirrels, lions, kangaroos, monkeys, deer, possums, gators, and more. Albino elephants aren’t exactly white; they’re lighter and pinker in color, and when they’re wet, they turn particularly pinkish.

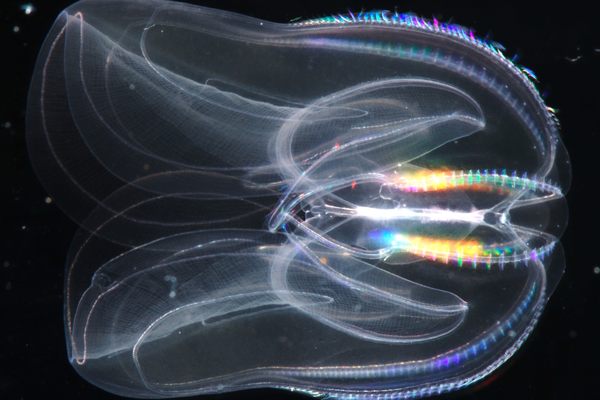

Sometimes, though, animals can lose most but not all of their melanin. In this condition, leucism, the animal’s skin might be stripped of pigment, but their eyes will still be dark.

Lobsters are a good example of how dramatic these little genetic changes can be. Usually, before they’re scalded bright red, they’re a mottled brown. But they can be bright blue. Or albino. Or split right down the middle into two different colors.

An orange and black split lobster. (Photo: Courtesy New England Aquarium)

“We know most about the blue lobster as we have bred them,” says Dr. Bob Bayer, the director of the Lobster Institute. “If you breed a blue male to a blue female you get all blue offspring.” But mostly, the exact genetic changes that change a lobster’s color are mysterious.

“I suspect they are variants of the same gene, but I don’t think this has been studied,” Bayer says.

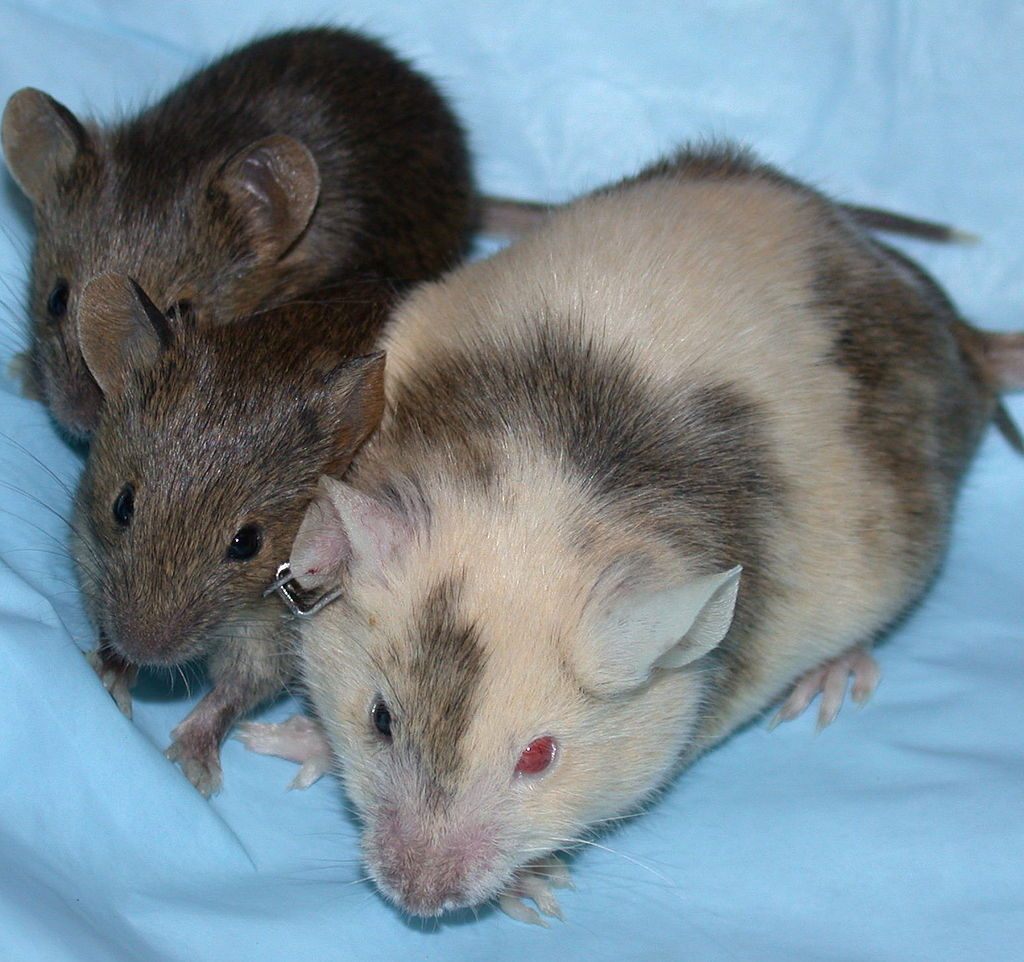

Lobsters aren’t the only animals that can be split into two differently colored halves. These “chimeras” occur in many species, not because certain genes change but because two different sets of genes are fused into one being early on in development. The two halves of the creature could have, potentially, become two unique individuals. Instead, they combine into one.

It’s even possible for one side of an animal to be one gender and the other side the opposite: that’s one reason why chimeric birds can have dramatically different plumage.

A bright blue lobster. (Photo: Sschemel/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

Sometimes, animals simply have too much pigment, and they turn dark black—melanistic. Small rodents, including squirrels and guinea pigs, are some of the more commonly seen melanistic animals. They’re even seen as valuable, sometimes. Edmundo Morales reports in The Guinea Pig that some folk doctors in the Andes prefer to use black guinea pigs in healing rituals.

The varied genetic mechanisms that create these surprising changes are rare, and they’re even more rarely seen by humans: a pink grasshopper has less chance of surviving life in a field than a green grasshopper. But they’re out there, and there are enough of them: Every year or so, a pink grasshopper or blue lobster is briefly famous when some human finds it, a local newspaper takes its picture, and those who see the story wonder how such a creature came to be.

“Spots”, the Leucistic alligator at the Audubon Nature Institute. (Photo: Audubon Nature Institute/flickr)

“Spots”, the Leucistic alligator at the Audubon Nature Institute. (Photo: Audubon Nature Institute/flickr)

A Kingfisher with Leucism. (Photo: Ian White/flickr)

A Leucistic peafowl at Scone Palace, Scotland. (Photo: John Mason/flickr)

A pink dragonfly. (Photo: Aleksei Semenov/shutterstock.com)

A pink dragonfly. (Photo: Aleksei Semenov/shutterstock.com)

A grasshopper with erythrism. (Photo: Mauro Rodrigues/shutterstock.com)

A blue red king crab (Photo: Courtesy Scott Kent/Alaska Dept. of Fish and Game)

A blue red king crab (Photo: Courtesy Scott Kent/Alaska Dept. of Fish and Game)

A chimeric mouse with its pups. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

A chimeric parakeet.

A melanistic guinea pig. (Photo: Rotatebot/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

A melanistic Caiman Crocodilus. (Photo: Jason L. Buberal/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 1.0)

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook