This Irish Academic Is Getting His PhD in Ghost Whiskey

And partnering with a distillery to resurrect one.

Irish doctoral student Fionnan O’Connor has been chasing ghosts. He is not pursuing the spectres of deceased warriors or poets, but rather forgotten Irish drinks. In a personal quest that has taken him from quiet university libraries to modern distilleries, he is determined to revive rare spirits made using old-fashioned methods and ingredients, specifically pot-still whiskies. As part of his Ph.D. thesis in ghost whiskeys, O’Connor is resuscitating pot-still recipes that have not been tasted for more than 100 years.

These long-lost beverages could soon enliven parties across Ireland, just like they did back in the 1800s. But that depends on whether O’Connor and Boann Distillery (his partner in reviving these whiskeys) can master discarded recipes, learn tricky distillation methods from bygone eras, and impress a panel of whiskey experts.

O’Connor admits he isn’t quite sure how he ended up at the helm of this project. Although he describes himself as a whiskey lover “since I was old enough to drink,” he was on an entirely different career path 10 years ago, studying medieval history and literature.

While completing that degree, at UC Berkeley, O’Connor began part-time work as a speaker at a whiskey bar and as a drinks-festival representative for Diageo, one of the world’s largest distillers. Both jobs came with a great perk: lots of free, premium alcohol. O’Connor quickly became besotted with whiskey. What started as a fling snowballed into a deep romance.

So deep, in fact, that it produced a book. Combining his literary education and whiskey knowledge, O’Connor published A Glass Apart: Irish Single Pot Still Whiskey in 2015. It was during research for this book, which included countless visits to distilleries, that O’Connor learned of the many Irish whiskeys that had disappeared over the past century.

“In 2014 there were very few Irish pot-still whiskeys left to write about,” says O’Connor. “Even for whiskey fans, Irish pot still as a style was something of an unknown drink in those days.”

In 1915, Ireland was the world’s leading producer of whiskey, pumping out 12 million cases a year from 88 licensed distilleries. Then, in the space of 30 years, the industry was decimated by two world wars, British trade restrictions, Prohibition in the United States, and Ireland’s bloody fight for independence from the United Kingdom.

Many of those 88 distilleries disappeared, along with the traditional recipes they used. By the 1970s, only two major whiskey distilleries remained in Ireland. Then, in 1988, powerful French distilling firm Pernod Ricard bought Irish Distillers and pumped money into marketing their whiskeys, launching a massive resurgence. Now Ireland is home to more than 30 whiskey distilleries.

This boom has made it a perfect time for O’Connor to launch his ghost-whiskey project. While researching his book, O’Connor secured funding for his Ph.D. from the Irish Government, which regularly offers grants to academics who investigate overlooked elements of Irish culture. In 2018, O’Connor began this thesis, which tracks the changes in mash bills (whiskey-grain recipes) from 1760 until the 1970s, by which time there were few remaining Irish pot-still whiskeys, a style made using a wider range of grains that boasts a thicker consistency and stronger flavors.

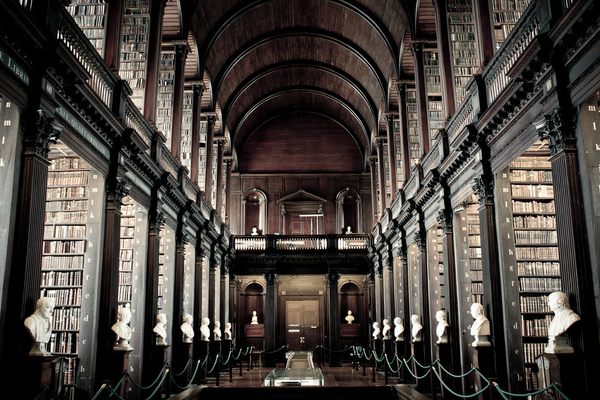

This requires a huge amount of legwork. The forgotten whiskey recipes aren’t just sitting on pub shelves, but scattered across Ireland, hidden in archives. So O’Connor traverses the country, visiting universities, libraries, and government offices to pore through old documents and search databases. Some days, his labor bears no fruit. Others, he’s thrilled to unearth recipes long consigned to history.

Then he faces the real task: lifting them off the page and bringing them back to reality. “Irish pot-still whiskey is a very different animal altogether,” O’Connor says of his obsession with reviving recipes of this style, comparing them to the lighter-tasting, more-popular Irish blended whiskeys. “The raw-barley viscosity of the old-school stuff was part of what drove me to write the book in the first place.”

A unique product of Ireland, pot-still whiskeys are differentiated, in large part, by the distillation device that gives them their name. Pot stills are bulbous distillation tools made from copper, whereas most popular Irish whiskeys are now made with taller, narrower column stills constructed from stainless steel. Pot stills and column stills both have a main vessel (called a kettle) that heats a mixture of water, grain, and yeast until the alcohol separates in vapor form, passes through one or more other vessels, and is condensed back into liquid.

The latter type of still has a column, separated by perforated plates, which sits above the kettle. As the vapor rises from the kettle, these plates further isolate the alcohol, which is pushed to the top of the column, gathering near-pure alcohol.

The pot still, meanwhile, produces alcohol with a much lower purity. This simpler, more old-fashioned distillation device sends vapors from the kettle up through a narrow, hook-shaped chamber and down into a spiral copper tube, inside which the vapor is condensed into liquid.

Column stills, then, are more efficient and cost-effective, which is why they dominate the modern market. And blended Irish whiskeys generally mix a cheaper spirit with a single-malt whiskey, which further lower costs compared to pot stills.

It is only in recent years, as the industry recovered, O’Connor says, that pot stills have begun to make a comeback. While modern consumers are accustomed to the light taste and feel of blended whiskeys, many whiskey connoisseurs appreciate the heavier, thicker product of pot-still whiskeys, which have a strong barley flavor and spicy notes.

The greater viscosity of pot-still whiskey comes from mixing raw barley grist into the malt. Pot-still whiskeys are then triple distilled and matured in oak casks. “That grist creates a much heavier, oilier drink than say a single malt,” O’Connor says. “That oiliness is what drives a lot of modern Irish pot still’s critical acclaim.”

To resurrect historical pot-still whiskeys, O’Connor sought out an Irish distillery willing to join his mission. He found Boann Distillery, a newcomer that began distilling in late 2019, led by reputedly Ireland’s youngest head distiller, Michael Walsh.

According to Boann director Sally-Anne Cooney, the biggest challenge of ancient-whiskey recipes is experimenting with grains other than the traditional barley, such as oats, wheat, and rye. This variety of grains means the whiskeys are less predictable in taste than the common blended varieties (some are spicier, some are heavier) and require careful adjustments of temperature, fermentation time, and yeast additions.

“I was mainly afraid that we’d break the equipment,” O’Connor says about their pot-still experiments. “Even in brewing, oats have a reputation for being tricky to work with, and I was afraid in the higher quantities they might turn to porridge and burst a pipe or something awful. I remember the day the highest oat mash went through and there was a huge sigh of relief.”

Several of these old pot-still whiskeys are now maturing in casks, and O’Connor is feeling optimistic. “Naturally [I was] afraid they’d taste like shite, but they all taste entrancing.”

O’Connor says these revived whiskeys will eventually be released to the public, but first they will be taste tested by a panel of 30 whiskey distillers, blenders, and critics from Ireland and Scotland. (The tastings have been delayed by Covid-19.) Scientists from Scotland’s Heriot-Watt University are also set to do a chemical analysis. Already, though, some whiskey enthusiasts have paid deposits to secure one of the casks created by O’Connor and Boann.

Some of these pot-still whiskeys may only be revived temporarily. Others, though, could be set for commercial comebacks. Boann is particularly excited about “Prestons Fine Irish Whiskey.” Prestons, then, is a ghost that may continue to walk the earth or, perhaps more accurately, dance on the palates of Irish whiskey fans.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook