Central Park Could Have Been Filled With Fussy, Fancy Gardens

If John J. Rink had gotten his way, that is.

Today, someone wandering all of Central Park’s 840 acres will encounter wooded rambles, rocky outcrops, vast meadows, glassy waters, ornate fountains and arches, and boulevards lined with trees. The notable urban green space is a hodgepodge of different landscapes, each of which was proposed, sketched, and built for visitors.

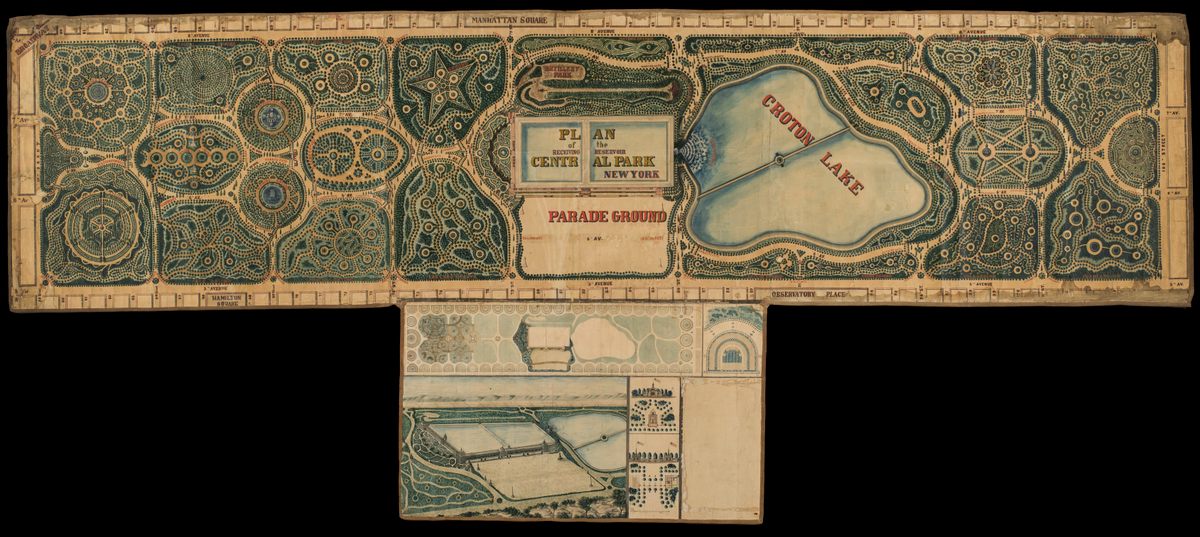

This particular, familiar mix, though, was far from guaranteed. Before Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux won the bid (and a prize of $2,000) to design the park in 1858, more than 30 other proposals were in the running. These reveal dueling 19th-century ideas about what public spaces should look like—and few are starker in contrast to the final design than the one submitted by John J. Rink.

The competition was open to all—and to level the playing field a bit, each entrant was given the same information and criteria. There was a topographic map of the land, and a handful of necessary features, including a parade ground, playgrounds, and at least four transverse roads at regular intervals. (In their winning design, Olmsted and Vaux proposed transverses below grade, to keep traffic moving without impinging on the view or pedestrian safety.) And none could exceed a $1.5 million budget.

One entrant proposed a pyramid, while George Waring Jr., a drainage engineer, went deep into the weeds on the park’s water infrastructure—and little else. The New-York Historical Society, which holds a copy of Waring’s entry, noted that while “the drawing is rich in topographical detail, it is sparing in actual design,” and its “footpaths cut across difficult terrain, with little regard for comfort.”

Then there was Rink’s. He included the requisite elements, but also scores of intricate gardens in the shapes of circles, stars, and labyrinths. While Olmsted and Vaux’s proposal—known as the Greensward plan—emphasized wide-open vistas, Rink’s was big on fussy, specific patterns. Aesthetically, at least, his proposal had more in common with the gardens of Versailles than what we see in Central Park today.

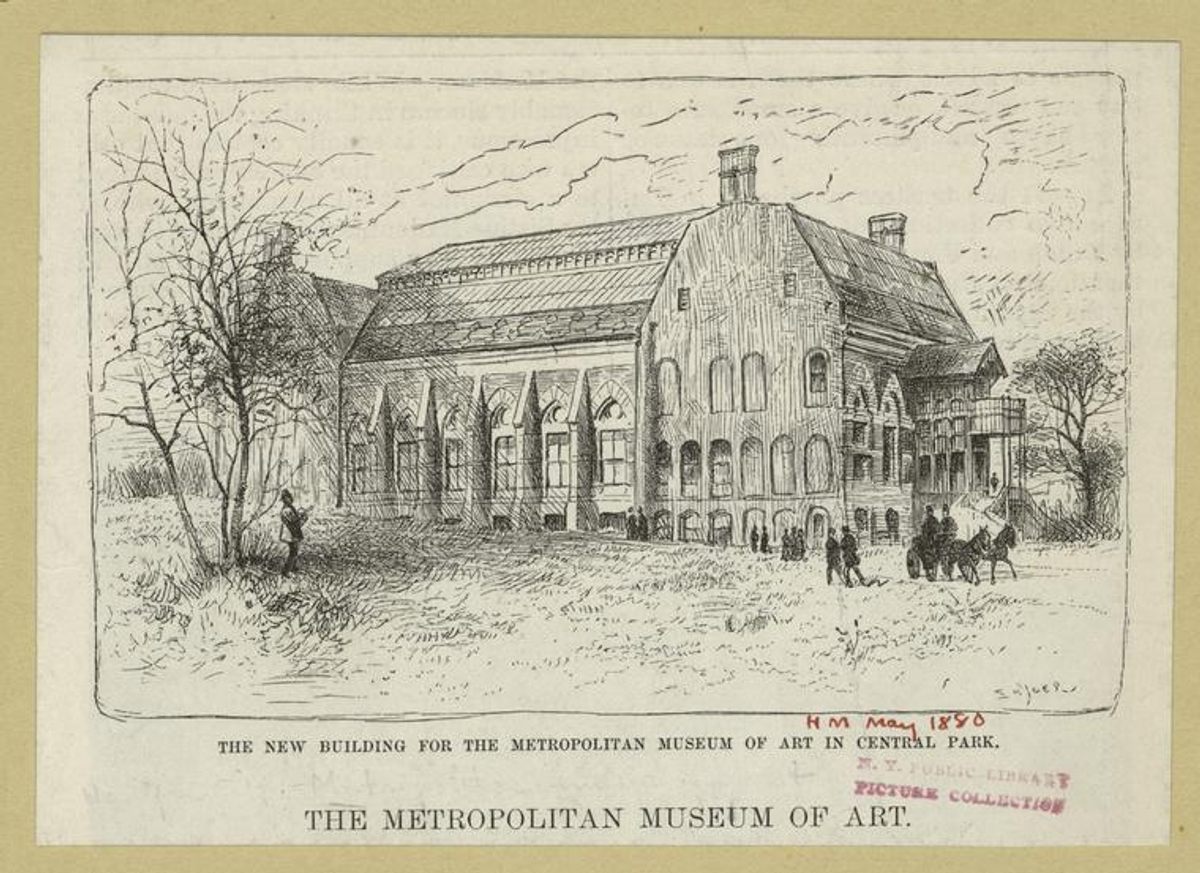

In Rink’s proposal, the Lake and wild Ramble of today would have been an ornate patch of greenery called the Star Ground. Sheep Meadow would have been a leafy roundabout. A parade ground would cover a swath of the park that now surrounds the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Rink was trained as an engineer, but he may not have appreciated how unwieldy his design would have been in practice. The winning design isn’t as “natural” as it looks—Olmstead and Vaux oversaw a team of 3,800 workers toiling up to 18 hours a day digging, blasting, and hauling and heaping soil and manure around the park, and it requires a great deal of upkeep today. But Rink’s winding, swirling islands of mannered greenery would have been costly and time-consuming to prune.

Still, to hear historians Elizabeth Blackmar of Columbia University, and the late Roy Rosenzweig tell it, the decision didn’t boil down to design alone. “Politics as much as artistic merit determined just how the nation’s first and most famous landscape park would be designed and built,” they write in The Park and the People: A History of Central Park. Olmsted and Vaux were chummy with the park commissioners, and recognized that the voters would gravitate to pastoral designs that evoked the rural landscapes.

New York City, of course, looks much different today than it did when Olmsted and Vaux were importing sheep to graze the meadows. How would Rink’s design look today, rolling out below blocky apartment towers and sleek skyscrapers?

Insurance company Budget Direct recently commissioned a rendering of Rink’s design, sprung off yellowed paper and plopped into the 21st century. To modern eyes, the patchwork of allées look like something out of a period drama. It’s a stark contrast to Olmsted and Vaux’s bucolic vision—even if their own triumphant submission was a whole lot less effortless than it appears.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook