For Victorian Men, the Mustache Comb was Everything

Facial grooming may have peaked in the era of Social Darwinism.

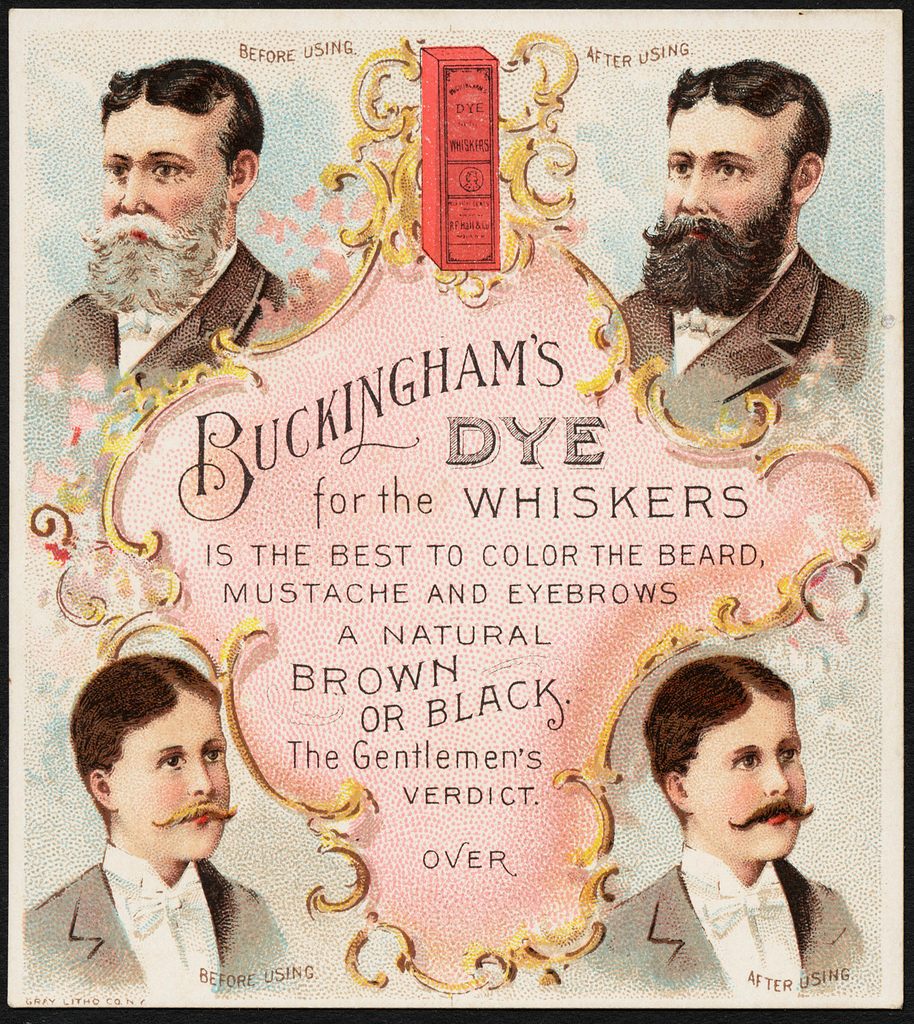

A trade card from 1870 for whisker dye, a part of mustache grooming. (Photo: Boston Public Library/CC BY 2.0)

On view in the open collections storage of the New-York Historical Society is a tiny object worthy of closer inspection: a 19th century mustache comb.

If you can look beyond its size and mundane function, a tale of Victorian manhood unfolds.

This mustache comb is of pocket size, measuring around 2 inches long and half an inche wide when closed and is composed of tortoiseshell with a silver mount adorned with a scrolling leaf border, Upon opening, the case becomes a convenient handle. The silver mark on the handle “F&B,” refers to Foster & Bailey, a company based in Providence, Rhode Island existing from 1878 to 1898. Beecher Ogden (1872-1963), a New York accountant and amateur photographer, donated this comb along with numerous library materials to the New York Historical Society in 1944. No photographs of Mr. Ogden seem to exist, but closer inspection of his mustache comb reveals a few orphan hairs, confirming its usage.

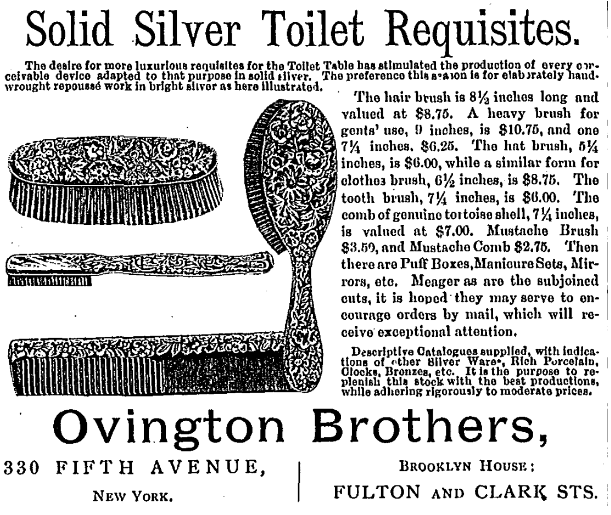

Perhaps the most surprising thing about this item is its price. In 1890, a solid silver and tortoiseshell mustache comb such as this one cost $2.75, equivalent to roughly $70 today. That a grooming article would be so sumptuously made and decorated speaks to its significance—this was not just a matter of hygiene, but identity.

The New York Historical Society’s tortoiseshell and silver mustache comb. (Photo: Courtesy of the Collection of the New York Historical Society)

A number of Victorian etiquette manuals contain mustache protocol. According to Mrs. Humphry’s Etiquette for Every Day, a perfect mustache is one “that actively bristles at the ends and turns neither up nor down.” This was a tamed mustache, unlike a curved droop at the corners, which suggested artistic temperament, or an upcurled mustache characteristic of the dandy. Cecil B. Hartley, in The Gentlemen’s Book of Etiquette and Manual of Politeness, cautioned men to tread carefully along the line of ideal mustache grooming, warning against the effeminacy of over-grooming and the indecency of neglect:

“It is not in either extreme that the man of real elegance and refinement will be shown, but in the happy medium which allows taste and judgment to preside over the wardrobe and toilet-table, while it prevents too great an attention to either, and never allows personal appearance to become the leading object of life.”

Hartley continues to say that the mustache “should never be curled, nor pulled out to an absurd length … [It] should be neat and not too large, and [avoid] such fopperies as cutting the points thereof, or twisting them up to the fineness of needles.”

An advertisement for grooming products from the 1890 Christian Union. (Photo: Sharon Twickler)

By the end of the 19th century, a man’s interior qualities were less important to his gender identity than the trappings of masculinity carried on his person. Physical appearance played an increasingly significant role in a man’s persona, particularly mastery of his body. By taming one’s whiskers a man asserted self control. A man should not overgroom, for that makes him a dandy, nor should he risk the indecency of neglect.

A properly groomed mustache achieved this middle ground by allowing a man to sport facial hair (demonstrating that he was manly enough to do so) and be clean shaven at the same time.

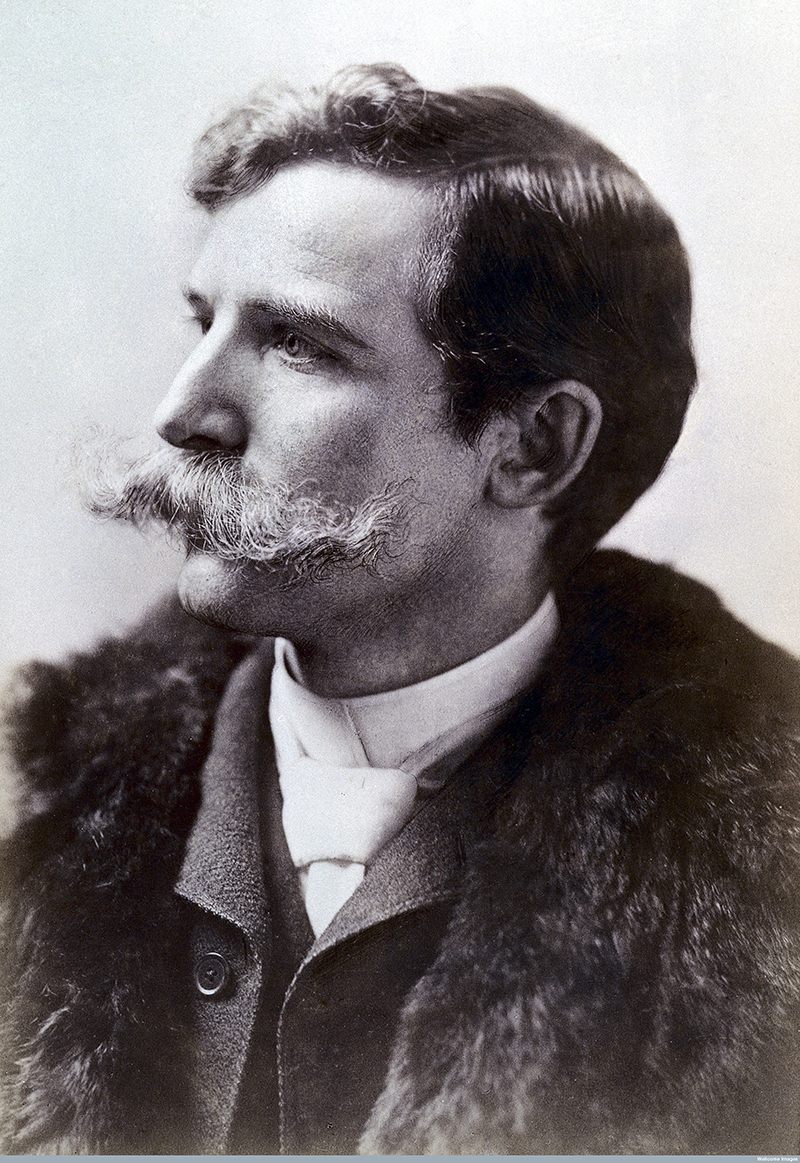

A luxuriant Victorian-era mustache as seen on Sir Henry S. Wellcome, 1890. (Photo: Wellcome Images, London/CC BY 4.0)

Superfluous hair took on special significance at a time when America’s face was rapidly changing. Decades of rising immigration and industrialization posed threats to Anglo-Saxon manhood. Also, Darwin’s theory of evolution was rocking American consciousness and as the idea gained wider acceptance, Social Darwinism emerged to justify socioeconomic inequality on the basis of natural selection.

Social Darwinists turned to the body, specifically hair, to note different levels of evolutionary progress. They believed that different racial groups represented different evolutionary stages, proposing that whites demonstrated more civilizing traits and were thus further evolved than other more animalistic races. This thinking extended to gender, as different racial groups were thought to represent varying degrees of manliness.

Charles Darwin. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-USZ61-104)

One text from 1886 so proclaimed that facial hair “attains its greatest development amongst the light-skinned and light-haired races.” one would think the hairy white man would be perceived as uncivilized, but as one Social Darwinist explained:

“…since the crown hair of the anthropoid brute–the chimpanzee, gorilla, orang-utan and gibbon–is of stiff, bristling structure…and this analogy with the anthropoids applies not only to the lower human races, with whom, as with the apes, the beard is scanty–it applies as well to the highest human races, with whom fulness [sic] of beard is a mark of racial superiority.”

While beards had the advantage of protecting a man’s face and throat from the elements, mustaches were interpreted as primarily ornamental. Author Henry Theophilus Finck pondered the mustache’s role in sexual selection, musing “sexual selection would not fail to seize on this ‘new departure’ in mustaches immediately in order to emphasize the sexual differences of expression in the face, and thus increase the ardour of romantic passion.”

He goes on to explain:

“…as man chooses his mate chiefly on aesthetic grounds, he habitually gave the preference to smooth-faced women, whereas woman’s choice, being largely based on dynamic grounds, fell on the bearded and moustached men, since a luxurious growth of hair is commonly a sign of physical vigour. Hence the humiliation of the young man who cannot raise a moustache.”

“Physical vigour” refers to a man’s ability to produce offspring. Certain phrases for facial hair like “raise a moustache” and “manly appendage,” are colorful euphemisms for sexual competence. Thus, a man’s inability to grow facial hair renders him effeminate and impotent.

The title page of The Gentleman’s Book of Etiquette. (Photo: Internet Archive/Public Domain)

Returning to Mrs. Humphrey’s Etiquette for Every Day, she also suggests how a lack of mustache, or one of insubstantial growth, may imply infertility: “A flaccid weakness of disposition is only too easily discerned in the scanty herbage that is all the most assiduous cultivation.” As an indicator of fertility, facial hair became a potent symbol of evolutionary favor and superiority, legitimizing the subordination of inferior races, whom were thought to not exhibit the same level of manly vigor and fertility. If natural selection, favored superfluous hair, than naturally hairy, white men were the rightful survivors of the fittest.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook