A Square, Flat Earth and Round Heaven Meant the World to Ancient China

For millennia, this cosmological principle guided everything from calendars to urban planning.

Reprinted with permission from The Globe: How the Earth Became Round by James Hannam, published by Reaktion Books Ltd. Copyright © 2023 by James Hannam. All rights reserved.

It was a big job, being emperor of China. He didn’t just have to run the country. The universe itself depended on him. He had a sizeable support staff of bureaucrats and eunuchs, but the buck stopped at the dragon throne. Dong Zhongshu (c. 175–105 BC), an adviser to Emperor Wu (156–87 BC), wanted to ensure his master understood the magnitude of his responsibilities. He explained that the emperor was the link between Heaven and Earth. If he ruled well, Heaven would support him by bestowing a clement climate and acquiescent population on China. However, if he violated the celestial order, for example by issuing judicial punishments that did not fit the crime, the emperor could expect warnings in the form of eclipses, droughts, and storms. If he didn’t heed the omens, Heaven might withdraw its mandate and the emperor’s dynasty would fall. Because they were an early warning system of empyrean displeasure, signs from the sky were of pressing importance, just as they had been to the Babylonians. From early times, the emperors maintained an astronomical bureau with the job of interpreting messages in the stars and giving rulers fair notice that their mandate was fraying.

Chinese chroniclers framed history with the ascent and decline of dynasties. When a new imperial family took the throne, it was like a youth that needed to be taught the ways of rulership, before reaching maturity when the empire was stable and at peace. But inevitably, dynasties, just like people, grew old and decadent. At that point, a new vibrant lineage would burst forth and overthrow the old, starting their own dynasty afresh. In practice, however, the mandate of Heaven was always awarded retrospectively. It wasn’t until a pretender had firmly planted his bottom on the throne that he ceased to be a wicked rebel and became the righteous instrument of destiny. Only then could he call himself the Son of Heaven.

In 221 BC, China was united under the Kingdom of Qin (pronounced ‘Chin’, from which we get the word ‘China’). Later historians would look back at the Warring States period before the Qin unification as an epoch of chaos and suffering, but it was also the time when many of the foundations of Chinese culture were laid. In particular, the ideologies of Confucianism and Taoism coalesced and began to enjoy enormous influence.

After the death of the first emperor in 210 BC, his realm threatened to fragment and return China to mayhem. However, one of the generals vying to replace him was able to reassert control in short order and founded the parvenu Han dynasty, which lasted until 220. The moral vision of Confucius (551–479 BC), centered on filial loyalty and ritual, undergirded the political philosophy that Dong Zhongshu urged upon Wu. Together, they enshrined Confucianism as the national ethic of China.

According to the Book of Documents, one of the four ancient Confucian Classics, the science of astronomy began with an order from the legendary Emperor Yao, who ruled China around 2300 BC. He sent out four men—one each to the east, south, west, and north—to determine the dates of the solstices and equinoxes by observing the heavens. Thus Emperor Yao instituted the first calendar by which all activity in his realm could be directed.

The emperor had to maintain an accurate calendar so that the rites necessary to keep the universe in balance were performed at the designated moments. The consequences of getting this wrong could be catastrophic. In 175, government officials reported that calendrical miscalculations had resulted in “evil folk rebelling and thieving … and robbers and bandits making endless trouble.” They demanded repercussions against the errant mathematicians responsible, urging that they ‘should receive heavy punishment for empty deceptions.’

Maintaining the calendar wasn’t easy. China used a lunisolar system that required frequent adjustments because the periods of the sun and moon are incommensurable. That means it is impossible to fit a whole number of lunar months into a whole number of solar years. According to some counts, the astronomical bureau went through almost a hundred calendrical systems in its 2,000-year history. An error of just a day was disastrous if it meant that a potential eclipse was missed or an important ritual was celebrated on an inauspicious occasion. In Europe, the solar calendar desynchronized from the seasons by ten days before the papacy introduced the Gregorian Reform to put it right in 1582. The emperors of China could never have tolerated such an egregious mistake.

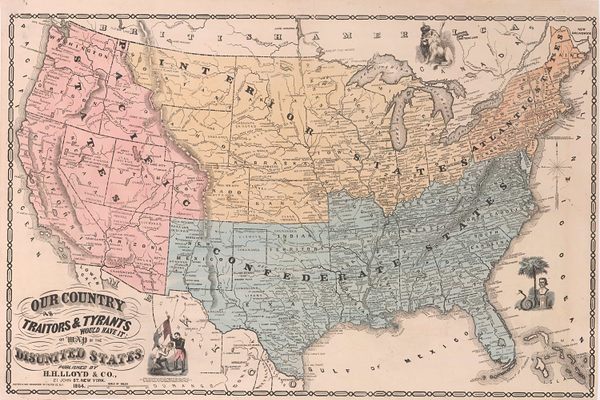

According to the Chinese world picture, as formalized under the Han emperors, the sky was round and Earth was square. The Huainanzi, a treatise on government prepared by Emperor Wu’s uncle, explains, ‘The Way of the Heaven is called the Round, The Way of the Earth is called the Square.’ Correlations could be found across nature to confirm the schema. For example, the Huainanzi went on to note the head’s roundness resembles heaven and the feet’s squareness resembles ground. Likewise, the turtle could represent the universe as a whole. The circular shell on its back corresponded to the sky, while the quadrilateral shell beneath its body symbolized Earth. The poet Song Yu, writing in the fourth century BC, used another analogy: ‘The square Earth is my chariot and the round Heaven my canopy.’

The reverse of a bronze mirror, cast during the Han dynasty and now in New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, illustrates this world picture. It is a decorated disc with a square inscribed within a circle. The rim of the mirror portrays watery chaos encompassing the round heaven inhabited by mythical beasts and gods. The square represents Earth, aligned with the cardinal directions of north, south, east, and west, with China itself occupying the center.

The Classic of the Mountains and the Seas, which reached its final form during the Han dynasty, extended the fourfold symmetry outwards. On each side of the central lands, there was a range of mountains, with a sea beyond. On the other side of the waters, four great wildernesses extended to the end of the world. Likewise, the Huainanzi says there were nine provinces in the central lands of China, arranged in a square and surrounded by four seas, beyond which there were eight other continents in the world, making nine in total.

To harmonize human affairs with nature, early rulers arranged plots of agricultural land into squares as a microcosm of the whole Earth. Each plot was divided into nine smaller squares, with the one in the center farmed by the community for the benefit of the lord. This was called the well-field system because it resembled the Chinese character for a well, and it remained an ideal long after it could no longer be implemented in practice. A nine-box grid also formed the basis of town planning. Admittedly, it wasn’t usually possible to arrange cities in perfect squares or farmland into equal parts. Nonetheless, important Chinese building projects, such as the Forbidden City completed in 1420, remained symmetrical, four-sided, and carefully delineated according to cosmological principles. Keeping to the same theme, to the north of the capital, the Ming dynasty built a Temple of Earth, featuring a square altar. A much larger Temple of Heaven, based around the circle, is located to the south.

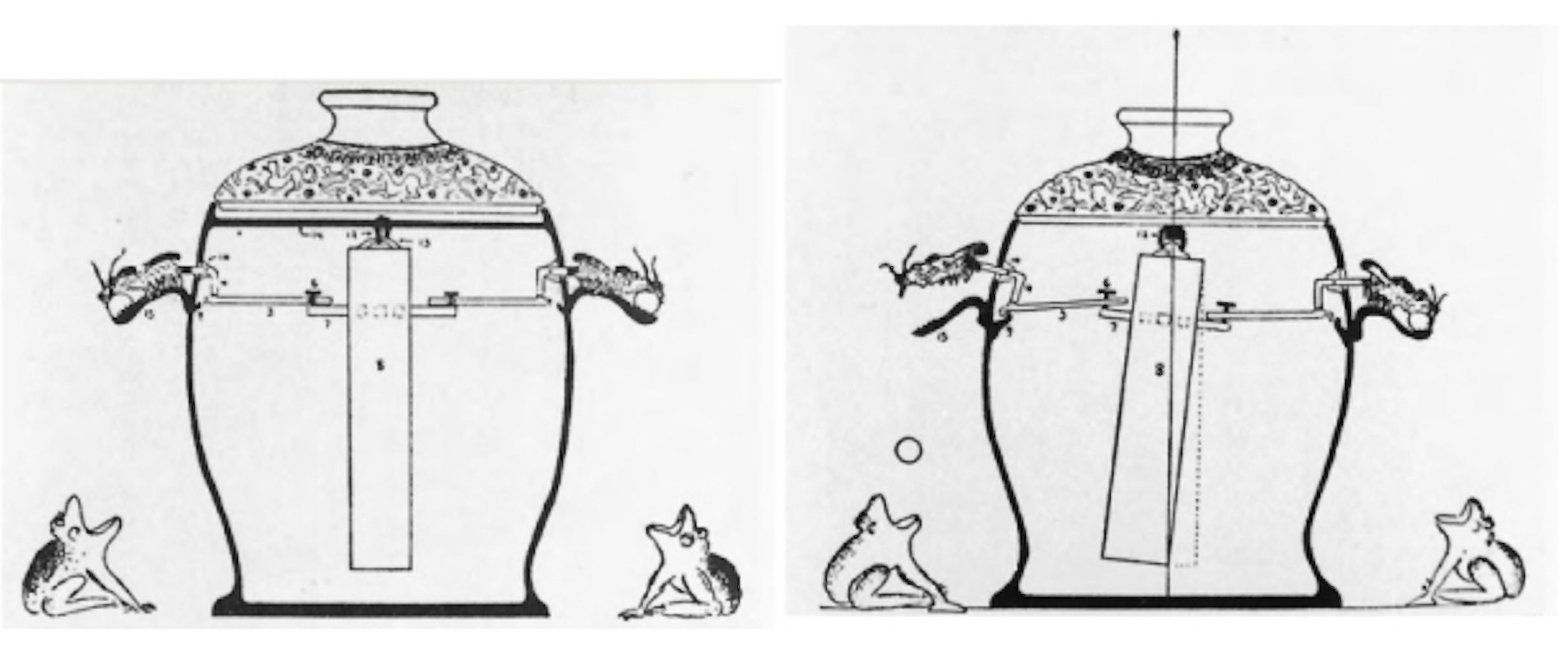

The heavenly canopy over a square Earth remained the dominant model in Chinese thought until modern times, but it was not unchallenged. Zhang Heng (78–139), who held the office of grand clerk under two of the later Han emperors, developed a spherical model of the universe, which was much discussed at the time. The grand clerk was responsible for 70 staff at the astronomical bureau, who submitted the annual calendar to the emperor, as well as noting important astrological portents. Zhang Heng was celebrated as an astronomer and mathematician, but also excelled as a poet and even invented a seismograph to detect earthquakes. As the epitaph on his tomb said, ‘With the arts of number, he exhausted heaven and earth; as a creator, he was equal to the creative [power of nature].’

He described the formation of the universe as beginning with a homogeneous mass, before continuing: At this stage, the original substance differentiated, hard and soft first divided, pure and turbid took up different positions. Heaven formed on the outside, and Earth became fixed within. Heaven took its body from the Yang, so it was round and in motion; Earth took its body from the Yin, so it was flat and quiescent.

On this basis, Zhang Heng postulated a spherical universe, the bottom half of which was full of water. Earth floated in the Ocean like an iceberg, the greater part of which was beneath the surface. The whole had an apparently arbitrary diameter of about 130,000 kilometers (80,000 miles). Nonetheless, the canopy system, which the Chinese respected as venerable and straightforward, retained its dominance. Zhang Heng was not forgotten, but his luster faded.

During the 20th century, the esteemed historian of Chinese science Joseph Needham (1900–1995) brought Zhang Heng’s cosmology to a wider anglophone audience. Unfortunately, Needham was defensive about Chinese ideas on the shape of Earth. In his Science and Civilization in China, he quoted Zhang Heng as saying, ‘The heavens are like a hen’s egg and round as a crossbow bullet; the Earth is like the yolk of the egg, and lies alone at the centre. Heaven is large and Earth small.’ Needham claimed that this ‘clearly shows how the conception of a spherical earth, with antipodes, would rise out of [the spherical universe]’. Certainly, comparing Earth to a yolk could be read as implying it is spherical, but it is clear from other parts of Zhang Heng’s writing that he had not meant to suggest this. Indeed, despite his novel ideas, he didn’t deviate from the established Chinese picture of a flat earth.

The Han dynasty lost the mandate of Heaven, and its empire fragmented in the early third century. However, China was still a nation of people with a shared language, shared traditions, and a history that bound them together. Even today, the ethnic group from the heartlands of the old empire are called Han Chinese. There was a powerful centripetal force towards unity, but it took three centuries after the fall of the Han to overcome the fissiparous inclinations of local rulers and pull China back together. In 618, a new Tang dynasty reunited all under Heaven. The phrase ‘all under heaven’ meant the central lands themselves, although it hinted that the rest of the world owed tribute to the emperor as well.

Chinese culture had evolved since the Han era. A lasting change was the introduction of Buddhism from India. Although Buddhism would all but die out in India itself, missionaries spread the faith across Central and Southeast Asia, as well as to the islands of Sri Lanka and Japan. They made many converts in China, where it joined Taoism and Confucianism as one of the major ethical systems. By the start of the Tang dynasty, Buddhists were well ensconced in Chinese society, albeit treated with suspicion by some of the learned elite. Missionaries continued to arrive from India, and Chinese monks set off in the other direction to collect copies of Buddhist and Sanskrit texts from the libraries of the Ganges Basin.

Among the Indian books brought to China were manuals on astronomy. So, it made sense that when the imperial calendar needed adjustment (again), officials looked to Buddhist monasteries for the personnel to sort the problem out. In 721, a monk called Yixing (683–727) was summoned by the throne to report on how the calendar could be reformed. The emperor had been getting agitated that it was no longer possible to accurately predict solar eclipses. While he had some familiarity with Indian astronomy, Yixing relied on conventional Chinese sources for his calendar, which was used for the period from 729 to 761. He was more innovative in his construction of an astronomical instrument called an armillary sphere. This was a framework of rings that represented the paths of the sun, moon, and other aspects of the heavens. Yixing added the ecliptic, which had always featured on Greek models, although earlier Chinese versions do not seem to have included it. This enabled him to show how the paths of the sun and moon intercept when there is an eclipse.

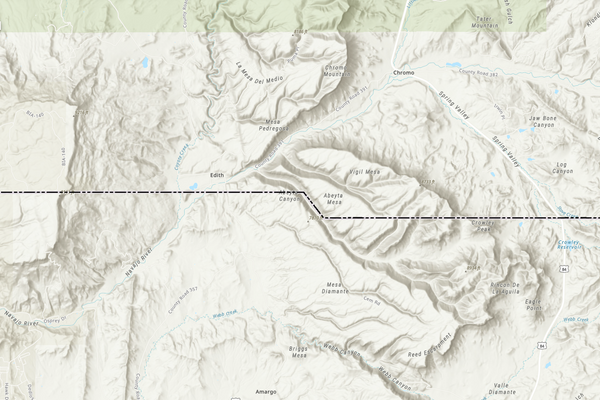

The emperor also commanded Yixing to carry out a survey of China. In particular, he needed to locate Earth’s center, since this was where certain rituals should best be carried out. It was traditionally situated at the city of Dengfeng, one of the ancient capitals of China. Yixing relocated it about 195 kilometers (120 miles) east to Kaifeng, another antique capital, on the south bank of the Yellow River. One of the geographical problems with a flat earth was finding the direction of true north. On the globe, that’s easy, at least in theory. Wherever you are, the shadow of the sun at midday is at its shortest and always points due north or due south, unless the sun is directly overhead and there is no shadow. But this doesn’t work if Earth is flat. In that case, the shadow only points exactly north at midday if you are standing on a line running directly south from the North Pole.

In 730, after Yixing had died and his calendar had come into use, he was accused of plagiarizing an Indian manual of astronomy that had been translated into Chinese a few years previously. This book, called the Navagraha-karana, described a cosmological system descended from the spherical astronomy of Aryabhata, with the adaptations needed for the latitude of the Tang capital city. Thus, it is one of the earliest works in Chinese that assumed Earth is a sphere. Although he was aware of the theory of the globe, Yixing didn’t use it for his calendar and the theory didn’t catch on. Later Tang astronomers lacked a background in the concepts used in the Navagraha-karana and so dismissed it as inaccurate.

Wracked by rebellion, Tang China became increasingly autarkic through the ninth century as the mandate of Heaven began to dissolve. A few decades of strife followed the dynasty’s fall before the Song took power in 960. Kaifeng, now recognized as the center of Earth, was chosen for the capital.

Song China was under constant pressure from tribes to its north and west. These groups gradually pushed south, taking over large swathes of the territory once ruled by the Tang. The Song capital at Kaifeng was captured in 1127. The dynasty regrouped and continued to rule southern China for another century and a half as the north fell to invading Mongols in 1234. Kublai Khan (1215–1294), a grandson of Genghis Khan (1162– 1227), founded the Yuan dynasty when he proclaimed himself emperor in 1271. He continued to push south and completed the conquest of the Song in 1279. By this time, the Mongols ruled a vast swathe of land from eastern Europe to the Pacific, including Central Asia, the Middle East, and Persia.

While Kublai Khan occupied himself subjugating China, his brother Hulagu (1217–1265) was crushing resistance to Mongol rule at the other end of Asia. In 1258, Hulagu’s armies sacked Baghdad, razing the city and massacring its inhabitants in a week-long orgy of pillage. Two years previously, he had captured Alamut, the fabled castle of the Assassins, without a fight. Despite his penchant for murderous rampages, Hulagu was interested in astrology, so housed the astronomers he captured from the Assassins in a new observatory at Maragha in northern Persia. It’s likely that he sent one of his menagerie of savants, a Persian Muslim called Jamal al-Din, to his brother Kublai with a package of astronomical instruments, including dials, an armillary sphere and an astrolabe. Jamal also carried a terrestrial globe—the first time one of these is recorded in China.

Kublai Khan acknowledged that his empire was home to a substantial Muslim population. To cater for their need for a calendar, he founded an Islamic astronomical bureau in his capital and appointed Jamal al-Din as its director. The Muslim and Chinese astronomical bureaus existed in parallel for several centuries, but there does not seem to have been much cross-pollination between them. So, while we might expect that communication between Persia and China would lead to the acknowledgement of the spherical earth by Chinese astronomers, this didn’t happen. They took no notice of Jamal al-Din’s terrestrial globe nor the methods of Arabic astronomy, which was an improved version of Ptolemy’s Greek original. In 1288, members of the Chinese astronomical bureau even attempted to get Jamal al-Din dismissed.

Furthermore, when Kublai Khan wanted a new calendar to mark the beginning of his dynasty, he knew it had to be acceptable to his Chinese subjects. Ignoring the Muslim bureau, he instructed a leading native astronomer, Guo Shoujing (1231–1316), to formulate it. Guo Shoujing was a brilliant instrumentalist and mathematician who, despite working within the traditional paradigm, produced a calendar that was more accurate than the Islamic one developed next door by Jamal al-Din. Indeed, there is no proof that Guo Shoujing’s work was at all influenced by Western developments. Instead, his calendar was a triumphant reassertion of the superiority of the Chinese way of doing things.

In the mid-14th century, the Chinese rebelled against their Mongol overlords and, after a period of civil war, the new Ming dynasty was installed in 1368. The first Ming emperor oversaw a return to Confucian values after the Mongol interim. The reign of his son, the Yongle Emperor (1360–1424), was characterized by a self-confidence that he wanted to project beyond China’s borders. This was the context for the famous voyages of Zheng He (1371–1433), a Muslim captured as a child, castrated and taken into royal service. In 1405, the emperor gave Zheng He command of an enormous fleet of junks to spread news about his benevolence to the known world.

In all, Zheng He led five voyages between 1405 and 1433, but he was not engaged in exploration. He knew exactly where he was going and how to get there. Merchants had plied the Indian Ocean for over a thousand years, taking advantage of the seasonal variations of its monsoonal winds. When ships crossed the open ocean, they expected to be blown by a following wind towards a coast they already knew about. They navigated along bearings from one port to another that they maintained by observing the stars.

If anyone had been looking for it, Zheng He’s far-flung travels could have provided plenty of evidence for the curvature of Earth. He traveled far enough south to lose sight of northern stars and to reveal those only visible towards the Antarctic. More obviously, every time his junks sailed away from the shore, the crew would have been able to watch coastal landmarks sink beneath the horizon.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook