This Five-Legged Cat Mummy Is Not as Strange as It Seems

A recently scanned cat mummy was probably not a scam, but the remains of animals that died on a sacred site.

When French scientists scanned a 2,500-year-old mummy in 2017, they expected to see the skeleton of an ancient Egyptian cat. What they actually saw was the image of several ancient Egyptian cats—specifically, five hind legs, most of three tails, and a little ball of cloth. Given that the biology of cats has not drastically changed since the 5th century BC, the biology of the cat mummy came as a bit of a surprise.

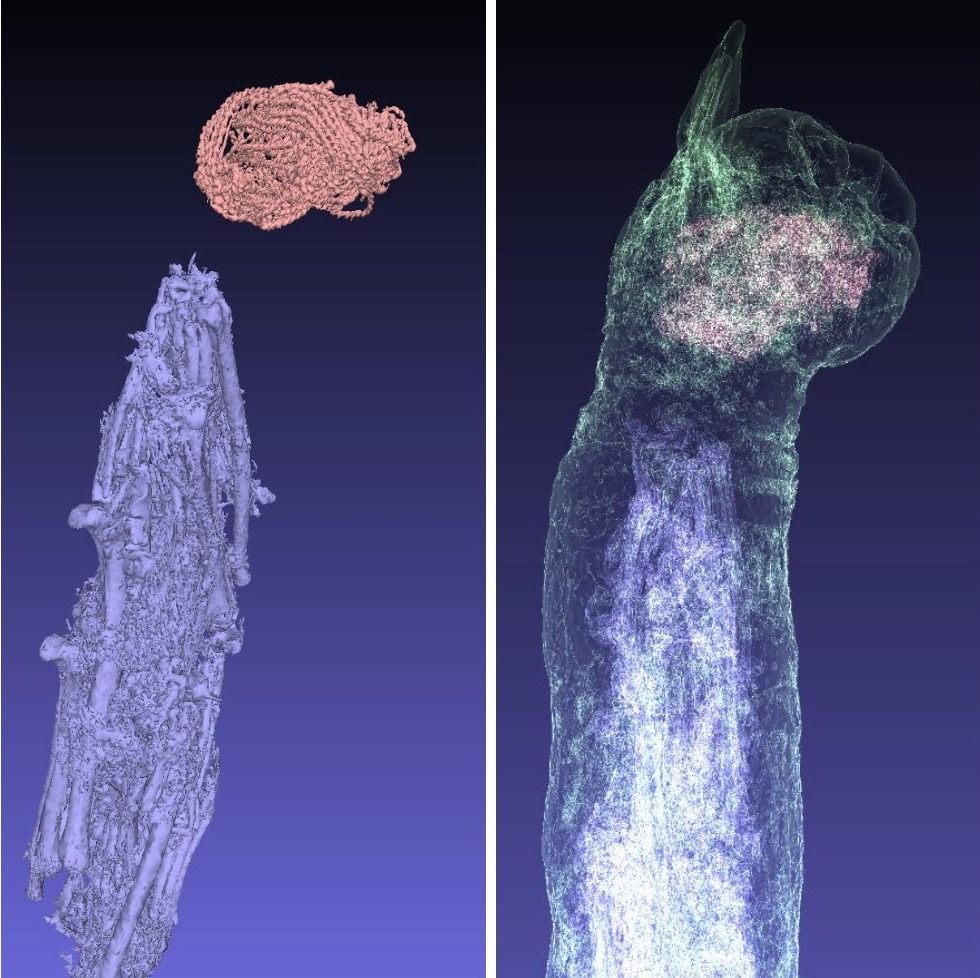

Though the cats lived and died in Egypt, the mummy resides in France, at the Museum of Fine Arts in Rennes. To see inside the mummy without unwrapping it, researchers from the National Institute of Preventive Archaeological Research (INRAP) performed a CT scan and reconstructed the skeleton in 3D, according to a statement from INRAP. “Some researchers believe that we are dealing with an ancient scam organized by unscrupulous priests,” Théophane Nicolas, a researcher at INRAP who assisted in the reconstruction, said in a statement. “We believe on the contrary that there are innumerable ways to make animal mummies.”

Though a five-legged, three-tailed cat may seem like a monstrous cryptid worthy of a scam, these potpourri-style mummies are more common than you might expect, according to Salima Ikram, a professor of Egyptology at The American University in Cairo and the editor of Divine Creatures: Animal Mummies in Ancient Egypt. “With mummies, the packaging does not always reflect the content,” she says. “We have various explanations for this, ranging from the cynical to the far less cynical.”

In a study of mummified cats and cat parts found in several tombs at the Bubasteum Temple in Saqqara, Egypt—a veritable feline necropolis—archaeologists identified 184 cat mummies and 11 “packets” that contained a smattering of cat bones, the archaeologists Alain Zivie and Roger Lichtenberg write in Divine Creatures. Several of these packets held the bodies of two to six cats, making them easy to spot due to their gigantic size.

In the case of this particular five-legged, three-tailed cat mummy, Ikram has three possible theories. First, it could be an example of Egyptian priests ripping off pilgrims who came to purchase mummies, now knowing that they often contained something other than what their exterior suggested. Second, the mummy could reflect the synecdochic Egyptian notion that the part of something symbolized the whole, and that the correct chants could render the cat bones into a whole cat in the afterlife, which Ikram says is an extrapolation of ancient magical texts. Third, the Egyptians believed that anything that died in a sacred space died with divine purpose, perhaps because they belonged to whatever deity who watched over the tomb, and were subsequently mummified. And sometimes, an incomplete skeleton could simply be a matter of human clumsiness. “When you mummify something, things can fall off,” Ikram says.

Luckily, the Rennes mummy holds one clue that might solve the mystery. Its dried flesh and bones had decomposed prior to their mummification, and were freckled with holes from the mouths of corpse-eating insects, Nicolas wrote in an email. With this knowledge, Ikram believes the Rennes mummy is a prime example of the third theory: The cats likely died around a tomb and, found in a state of decay, were made into mummies. “With this particular mummy, they gathered pieces of dead animals within the sacred space to give them a happy afterlife,” she says.

In recent years, the actual contents of animal mummies have been studied far more than human mummies, as their smaller size makes them easy to slide into a scanner, Ikram says. And as more mummies are scanned, more reveal surprises. Two-thirds of the cat mummies collected at Bubasteum showed evidence of a violent death, suggesting that priests would often raise cats for the purpose of slaughter and eventual mummification. These mummies would not show bites like the Rennes mummy, because they would have been bandaged soon after death.

But even in the case of these more slapdash, inconclusively-sourced cat mummies, Ikram is wary of calling these mummies scams. Instead of setting out to deceive pilgrims with mummies made of incomplete skeletons, priests likely were doing the best they could with such a high demand for cat mummies and a limited supply of cats, Zivie and Lichtenberg write in Divine Creatures. Maybe for mummies, what’s on the inside doesn’t always count.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook