The Story of the Teacher Who Desegregated New York Transit

In 1854, Elizabeth Jennings was forcibly kicked off a horsecar. Her fight changed the city.

This story is excerpted and adapted from Jerry Mikorenda’s book, America’s First Freedom Rider: Elizabeth Jennings, Chester A. Arthur, and the Early Fight for Civil Rights.

Eighteen fifty-four was a year of extremes in New York City. As noted in the New York Daily Times, “it was remarkable for wrecks, murders, swindles, defalcations, burnings on sea and land.”

The year began with high hopes for a long-awaited railroad line on Broadway and ended with the arrests of several officials from the Harlem Railroad Company for stealing. By midyear, the first Cholera Hospital opened at 105 Franklin Street, followed by another on Mott Street, only to have the commissioners of health accused of suppressing data about cholera deaths as fear of an epidemic gripped Manhattan.

In a city of 515,000 residents, 500 children died the week of July 15—two-thirds were infants. Of the 817 New Yorkers to die overall, 12 were recorded as “colored.” About a mile or so uptown, Elizabeth Blackwell, the first woman in America to receive a medical degree, was busy establishing the New York Dispensary for Poor Women and Children by the newly rising tenements near Tompkins Square Park. At first, no one trusted a female doctor. But within two years, abolitionists such as William Lloyd Garrison helped her raise enough money to purchase the old Roosevelt home at 64 Bleecker Street and expand her services. (Today it’s known as New York-Presbyterian/ Lower Manhattan Hospital.)

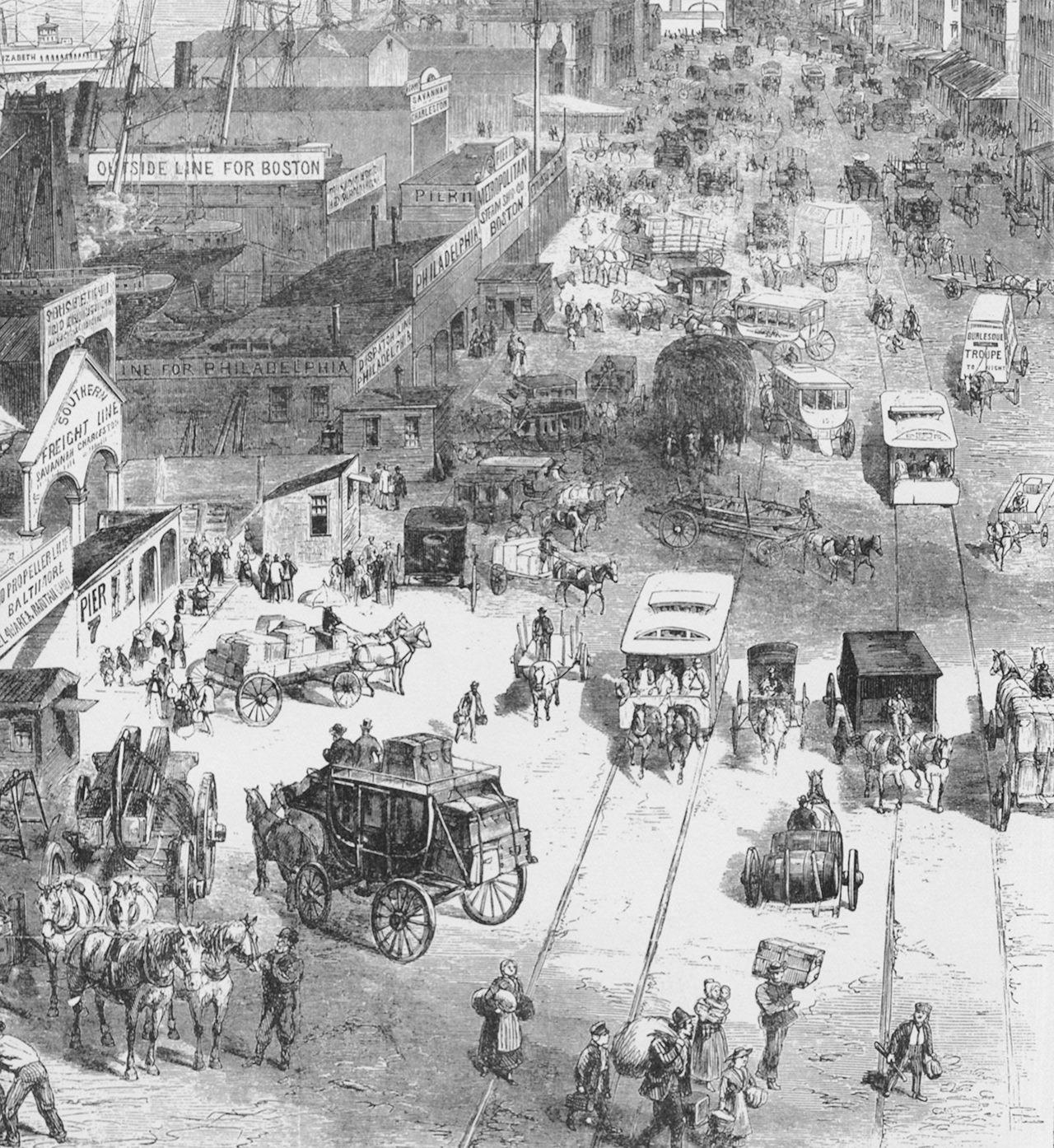

In mid-July of 1854, a crippling heat wave suspended work in the shipyards. Sunstroke and “brain fever” caused dozens of deaths. Dead animals, horses mostly, were a problem. Their carcasses were left in the streets where they fell from heat exhaustion. That year there were 22,500 horses in Manhattan pulling streetcars, omnibuses, and coaches, according to Hilary J. Sweeney in the American Journal of Irish Studies. Decay, flies, and filth were everywhere, including an estimated two hundred tons of manure left daily on the streets.

The heat and stench must have affected schoolteacher Elizabeth Jennings’s mood as she hastily readied for services on the morning of Sunday, July 16. As the organist for the First Colored American Congregational Church, it was important for her to arrive early and rehearse with the choir. She was leading her church’s music program at a time when most organists and choir leaders were men.

She was running late, and temperatures were as high as 98 degrees. In heavy Sunday-best garb, Elizabeth and Sarah Adams began their two-mile walk from Elizabeth’s home at 167 Church Street, a wood-framed boardinghouse with a first-floor store and a slate roof where she lived with her parents. Taking on boarders was a common practice in 19th-century New York, with about 30 percent of the population living in some 2,600 registered homes. Elizabeth’s father, Thomas, was listed as owner of the building, where he ran his tailoring and dry-cleaning business. (Thomas Jennings, in fact, was the first to patent a commercial dry-cleaning process, and the first African-American to be granted a patent for anything.) Also living there were two white families, those of Patrick Fitzgerald, a bricklayer, on one floor and W.S. Martin, a boatman, on another. The house had an open lot in the back used to grow vegetables, and a coal yard was located about a block away.

Across the road was the Mother African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church. on the corner of Church and Franklin Streets. On the opposite corner was J.B. Purdy, a grocer in a mixed neighborhood. Living nearby were an upholsterer, laborer, teacher, and police captain. A block off Broadway, this was a well-to-do area with many brick-and-stone homes with large skylights. The Jennings’s home was on the edge of it.

A section of the road before the Jennings’s home was nicknamed the “Holy Ground” because of its many high-class brothels. While walking in the direction of the Third Avenue rail line, Elizabeth and Sarah headed for the streetcar stop. To reach the Third Avenue line, they turned right onto Pearl Street and hurried a few short blocks toward Chatham. To keep their dresses from dragging through the ever-present street offal and grime, in a ladylike fashion, they used a skirt lifter called a page or pulled on the chain of a chatelaine that raised the material from the soil without exposing the ankles.

The two women made their way down Pearl Street and caught their breath at the corner of Chatham Street. There, Elizabeth saw a horsecar in the distance slowly making its way uptown. She felt lucky that one was coming, she later explained in an interview with the American Woman’s Journal. A rider could wait 15 minutes or more for a bus on a Sunday. The light green car was 16 feet long and could seat 24 passengers. It appeared half-full as Elizabeth waved to flag the driver down. The deafening sound of the iron wheels scraping along the metal track as hooves stamped over stone suddenly ceased. Elizabeth swung herself up onto the high step-up platform in one motion. According to a reporter from the American Woman’s Journal, while she waited for Sarah to join her, the conductor approached.

“You must wait for the next car,” he said, pointing to the street.

“I am in a hurry and cannot wait for another car,” she replied, moving toward the seats.

“But that car has your people in it,” he added, motioning her back onto the boarding platform. “It is reserved for them.”

“I have no people,” exclaimed Elizabeth, becoming irritated. “This is no special occasion; I wish to go to church as I have been doing for the past six months and I do not wish to be detained.”

The conductor would not let Elizabeth take a seat and asked her to leave the car. She again refused. The conductor demanded she wait in the street, but Elizabeth wouldn’t budge.

“I will wait here on this platform until the other car arrives,” she added, with a firmness in her voice that could only come from a teacher.

An awkward silence drifted over the bus. People were used to travel delays—cows lying down on tracks, firefighters’ hoses crossing their path, or a broken-down wagon blocking their progress. All these things were to be expected. The midday heat must have been unbearable, making the minutes seem more like hours. They waited in a standoff. Two African-American women stood immovable on the platform, blocked from going any farther inside by an irascible white conductor.

Finally, the bus that seemed so far away was upon them. Elizabeth could see the sign in front that said, “Colored People Allowed in This Car.”

“Is there room in your car?” Elizabeth shouted.

“No,” the driver said, pulling up his horses. “There is more room in that car than there is in mine.”

Elizabeth and Sarah thought that would be the end of it. Once again, they attempted to enter the streetcar, only to be prevented once more by the conductor. He stood in the doorway with his arms braced across the entrance. Unable to proceed, they simply stared back at him.

“I have as much time as you have and can wait as long,” he said with a sneer on his face.

“Very well, we will see,” Elizabeth snapped back.

One can imagine the collective groan from the bewildered riders as the saga continued with no end in sight. Even the horses, used to having a certain cadence to the day, must have begun to buck and crane their necks as if trying to see beyond their blinders. Growing impatient, the driver shouted at the conductor that he needed to move the bus. Now all eyes were on the conductor. Wiping the sweatband inside his cap, he threw his arms in the air, “Well, you may go in,” he barked at the women while taking their nickel fare. “But remember, if any of the passengers object, you shall go out, whether or not you want to, I’ll put you out!”

That might have been the end of it for many people. Jennings was tired of being bullied. Tired of second-class treatment. Tired of having the color of her skin being used as an excuse for vile behavior.

“I am a respectable person,” she snapped, admonishing the conductor. “Born and raised in New York and I have never been insulted before while going to church.”

“I was born in Ireland, and I don’t care where you were born!” exclaimed the agitated conductor “You’ve got to come out of this car!” Ever the educator, Elizabeth gave the Third Avenue conductor a lecture on equality that still rings true today.

“It makes no difference where a man was born; he’s no better or worse for that, provided he behaves himself,” she said, “but you are a good-for-nothing, impudent fellow, who insults genteel people on their way to church.”

“I’ll put you out of this car,” he shouted.

“Don’t you lay a hand on me,” cried Elizabeth.

Suddenly turning, the conductor grabbed Elizabeth by the shoulders before she could sit and pushed her back toward the door, she grabbed a window sash and held on for her life. Unable to remove her on his own, the conductor yelled for the driver to “fasten his horses” and assist him. Together they knocked Sarah back down the stairs. Turning to Elizabeth, the two men grabbed her by each arm, breaking her grip on the window. Then they dragged her out onto the platform to face a several-foot drop to the street.

“Murder, murder!” she screamed.

“Stop, you’ll kill her, don’t kill her!” pleaded Sarah.

Elizabeth was tossed headfirst into the street as one might throw a bag of trash or old clothes. In a billow of dust, her face scraped against the filthy cobblestone road, leaving her bleeding, bruised, and dizzy from the fall. A part of her just wanted to lie there and cry. Her ribs hurt, her shoulder stung, and it was hard for her to see.

She got to her knees, stood, and began to limp away from the conductor. Then she stopped and slowly turned around, wiping grime and blood from her face. She took two steps back toward the horsecar to pick up her hat. She placed it on her head and leapt back onto the stairs of the streetcar. The shocked conductor could scarcely believe his eyes, but his astonishment quickly turned to anger.

“You shall sweat for this,” the enraged conductor cried, pushing her against the wall.

In his next breath, he ordered the driver to “rise on the box and lash the horses” and do so without picking up any passengers. The car took off without Sarah, leaving Elizabeth alone with the conductor.

“Do not stop until we reach an officer or a station house,” he cracked, with confidence.

They drove recklessly fast, sending riders sliding off their seats. The car bolted down Chatham, quickly passing Roosevelt, James, and Oliver Streets before the wide turn onto Bowery. On the corner of Walker, about a half-mile from where they started, the conductor flagged down a policeman. As the officer entered the bus, the conductor explained that his orders were to only allow colored persons on board if none of the other passengers objected, and if they did, it was his job to show the Black rider the door. Perhaps a handful of people remained on the bus when the officer asked if there were any objections. No one spoke out against Jennings in words or gestures. It seemed the only one who objected was the conductor.

Regardless, the officer wouldn’t listen to anything Elizabeth had to say. He shoved her back toward the platform several times and then pushed her down the car stairs.

“I shall get redress for this,” she yelled, holding her head high.

“Do, if you can,” laughed the policeman.

“What is your name?” she asked, pointing at the conductor.

“Moss, Edwin Moss,” he replied, also giggling with delight.

The conductor wrote his name and “car No. 7” on a scrap of paper and threw it at Elizabeth, but she saw the number 6 painted on the side of the car. The officer then chased her off, “drove me away like a dog,” she later recalled in her interview with the American Woman’s Journal.

“Get out of the street,” the policeman barked, “and don’t be raising a mob or fight.”

Beaten and torn, Elizabeth limped down Walker Street toward home. She passed a deserted coal and lumberyard, sawmill, and empty Panorama Hall. After a short distance, she realized a man was following her. Even on a Sunday afternoon, being alone on city streets with skip tracers abducting Black women and children at will was risky and dangerous. Timidly, the man approached and introduced himself.

“My name is Latour,” he said in a thick German accent. “I witnessed the whole transaction in the street as I was passing. I live at 148 Pearl Street, where I am a bookseller.”

Elizabeth trudged onward. Her spirits were lifted by the kind act of this stranger. She continued, suffering yet determined that this day wouldn’t be forgotten.

That afternoon, word of Elizabeth’s brave stand and brutal assault quickly spread throughout the African-American community. In a show of support, her church called a public meeting the next day to decide a course of action. Elizabeth was unable to attend the meeting herself because, “I am quite sore and stiff from the treatment I received from those monsters in human form yesterday afternoon,” she wrote from home.

In their annual reports to the state railroad commissioners, each rail line must catalog accidents under one of eight categories. “Fell or thrown from cars” was listed as a possible cause for death that must be reported by the railroad. In her absence, she provided a written statement about the attack that her father read. It served as a basis for newspaper accounts appearing in the New-York Daily Tribune and Frederick Douglass’ Paper.

The meeting at the church was a lively expression of outrage, unity, and community empowerment. This was a time for action. By that, those attending meant legal action. Somehow the Third Avenue Railroad must be made to own up to the behavior of its employees and recognize “colored citizens [have] the equal right to accommodations of ‘transit’ in the cars,” as the Tribune reported from the meeting in its July 19, 1854, issue. A committee organized by her father was formed to bring about a civil lawsuit.

All those present unanimously passed three resolutions. The first stated that the railroad’s behavior was “intolerant” and called for the “reprehension of the respectable portion of the community.” A second sought to sue the railroad and demanded a ruling on the legal status of African Americans using the transit system. The last resolution targeted media outlets such as the Tribune and Douglass’ Paper to ensure that Elizabeth’s case would be reported in the press.

Enthusiasm during the meeting ran high. It was time for free Black New Yorkers to be recognized as equal citizens. Everyone in the audience knew that being able to go where you wanted when you wanted was the first step in reaching equality. But buried in those three resolutions was a dose of reality. The words “if possible bring the whole affair to legal authorities” underlined the difficulties the group faced. Who would take on the cause of a Black female looking for equality in a city bonded to the slave trade?

The proceeding closed on a spiritual hymn. The thoughts of everyone in the church were on the fallen schoolteacher at home, humiliated and physically ailing. As they raised their voices in unity, it remained an open question if they would ever be heard beyond the church walls on Second Avenue and Sixth Street.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook