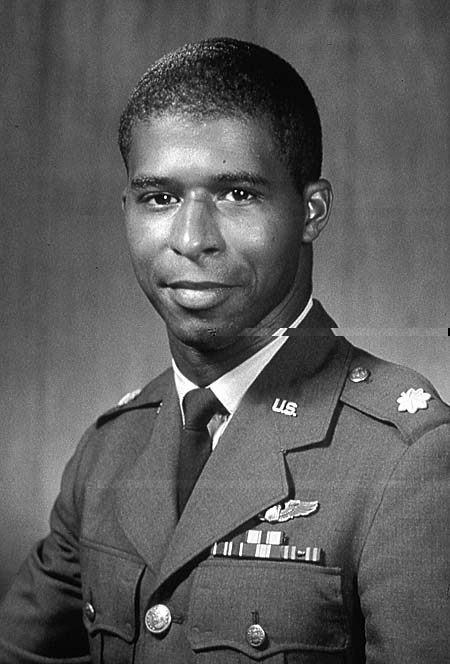

Remembering the Groundbreaking Life of the First Black Astronaut

Robert Lawrence Jr.’s accomplishments are finally being recognized.

Robert Lawrence, Jr. isn’t a household name. But he’s one of those people who leave big footprints. People walk through them for years, decades even, without knowing exactly who left them.

Lawrence’s name is probably one you should know, though. Not only was he was part of a secretive 1960s Air Force program called the Manned Orbiting Laboratory (MOL), but Robert Lawrence, Jr. holds another important and pioneering title; he was the United States’ first black astronaut.

Born in Chicago, Illinois in 1935, Lawrence was a gifted scientist, graduating from Bradley University with a degree in chemistry by age 20. He went into the Air Force soon after, completing pilot training and becoming an instructor for trainees. A busy schedule, but not too busy for Lawrence to also earn his PhD in physical chemistry at Ohio State in 1965.

He went on to become a researcher for the Air Force Weapons Laboratory at Kirtland Air Force Base, all the while still actively flying planes. According to NASA researcher John Charles, “by 1965, he had accrued 2,500 hours of flight time, 2,000 of them in jets.”

Lawrence was only 30 years old, but his talent was getting him noticed. When he completed test pilot training in 1966 (being a test pilot was a requirement for the MOL), he, along with three other pilots, was assigned to the program as an Air Force astronaut.

In a 1967 New York Times article on his historic achievement, Lawrence was low-key about his success, attributing it to his large support system, including his mother, teachers, and mentors. But he was firm in the belief that this was an important step in the country’s fight for racial equality. His selection, he told the newspaper, was “just another of the things we look forward to in the normal progression of civil rights in this country.”

The Manned Orbiting Laboratory had an official mission nearly everyone could get on board with; conducting experiments in space. The program was approved in 1962 and assigned to the Air Force. A 1963 press release noted that the program’s aim was to “increase the Defense Department effort to determine military usefulness of man in space.” Astronauts were going to explore the cosmos, or, more accurately, figure out if the military even needed to be exploring the cosmos. In a space-race-obsessed America, this program was, at least publicly, another noble attempt at touching the stars.

However, what the press release left out was the program’s main mission; placing a manned surveillance satellite in space so that the U.S. could spy on the Russians. The MOL was less about star stuff than it was about spy stuff. The program’s real goal, according to the Department of Defense’s National Reconnaissance Office,* was to “acquire photographic coverage of the Soviet Union with resolution better than the best system at the time.” Lawrence wasn’t just going to fly into space, he and his MOL brethren were tasked with photographing Soviet missile targets.

However, the MOL never launched its mission; funding struggles, competition with NASA and other Department of Defense projects, and improving unmanned satellite technology meant the program never got off the ground and was scrapped in 1969. Lawrence, however, didn’t live to see all of this. His short but distinguished career ended in tragedy when he was killed in 1967 after his plane crashed on the runway during a training flight.

Although they completed similar training to NASA astronauts, the men of the MOL were not officially considered astronauts, as the Air Force projects and the space agency were not connected. In 1997, however, after an Air Force review, Lawrence and all of the men of the MOL were finally classified as astronauts, cementing their place in American space history.

Lawrence may not have made it into orbit, but his pioneering accomplishment was acknowledged in a ceremony at Florida’s Kennedy Space Center on December 8, the 50th anniversary of his death. His achievement paved the way for those who came after him: Guion Bluford, who in 1983 became the first black astronaut in space and Dr. Mae Jemison, who became the first black woman in space in 1992, among others.

“He would have been the first black person to fly in space,” said former astronaut and fellow MOL member Bob Crippen at the ceremony honoring his life. “And he would have been famous. And he’s still famous with a lot of us, and he is still missed today.”

*Correction: The story has been updated to reflect that the National Reconnaissance Office is an agency of the DOD, not NASA.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook