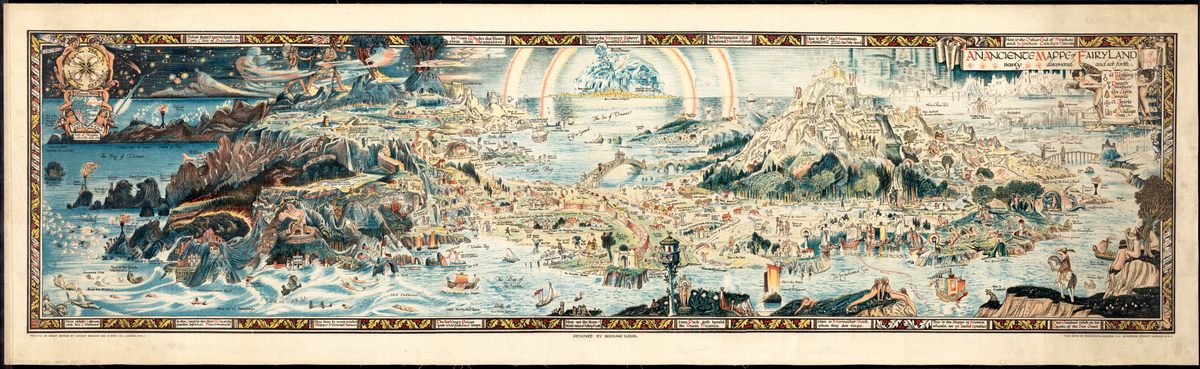

For Sale: A Historical Map of the Imagination

Bernard Sleigh’s dreamland mashes up myths, fairy tales, and nursery rhymes.

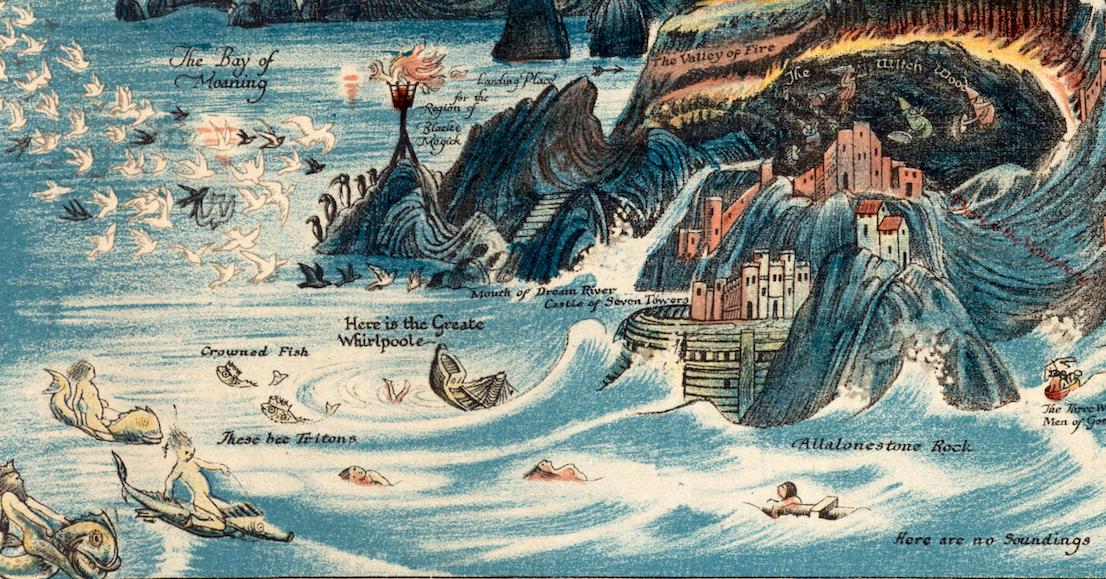

The journey begins with a stormy sea. There, waves lash the shore and tritons ride piscine steeds, while a wooden ship and an unfortunate soul are half-sunk nearby, in a white whirlpool.

At first glance, things aren’t much better on land. The shore is rocky and steep. A note beneath a darkened castle cautions: “No landing here.” Werewolves snarl from a cliff, and a pair of dragons claw toward Castle Warlock, a fortress bordered by the yellow-orange Valley of Fire and the inky-black Witch Woods, where a quartet with pointy hats soars on broomsticks. Nearby, three terrible, unknowable creatures—claws extended and mouths open—poke out of holes in a mountain. “Here dwelle horned Monsters,” a warning reads, in case it wasn’t obvious.

But this nightmarish menagerie is just one corner of a map by Bernard Sleigh, a British author and illustrator. Printed in 1917, An Ancient Mappe of Fairyland, Newly Discovered and Set Forth beckons viewers to tromp through an imagined landscape populated by creatures and characters from ancient myths, Arthurian legends, folklore, and more contemporary nursery rhymes. It’s a whimsical scene, produced at a time when wonder was sorely needed.

As viewers wander toward the middle of the six-foot-long map, they encounter Peter Piper wading into placid water, while Puss in Boots strikes a pose on shore. Humpty Dumpty sits safe atop a brick wall (for the moment), and Rock-a-Bye Baby dozes on a leafy treetop. Old Mother Hubbard and Miss Muffet are neighbors in a block of row houses, while Red Riding Hood and Cinderella live farther afield. Continuing on to the right, figures from classical myths appear in battle or repose—centaurs and nymphs, Hercules and Perseus, Andromeda and sirens. Sometimes, the characters mingle in surprising ways: Narcissus gazes at his reflection just outside the entrance to Merlin’s woods.

It is said that Sleigh initially sketched a prototype of the map several years earlier, to entertain his kids. The large panorama was later published and marketed as nursery decor. A version soon traveled to New York, where it was displayed in the children’s division of the New York Public Library. Then, two decades later, the fantastical illustration reemerged as decorative fabric. Across the dense landscape, “everything is very familiar,” says Lauren Chen, reference and cataloguing librarian at the Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center at the Boston Public Library, who included the map in a 2015 exhibition about literary landscapes. The figures who populated the map—and imaginations—a century ago are still hanging around. Now, a print of the epic tableau is for sale at Geographicus Rare Antique Maps.

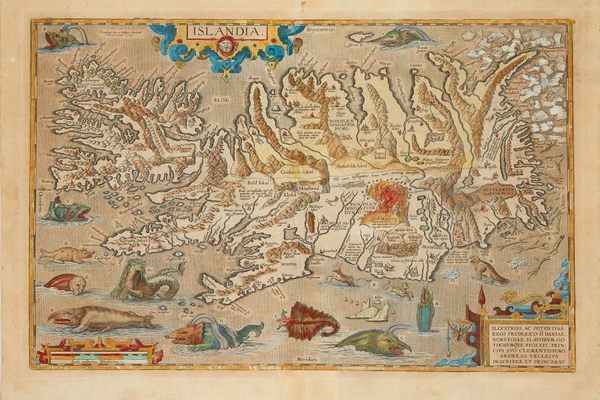

Though the map is whimsical, it appeared on the tail end of a boom in allegorical maps that had a political cast. These were intended to be persuasive or propagandistic, and “utilized symbols of nationality and unity or highlighted differences between other nations comically,” says Philippa (Pip) Gregory, a historian at the University of Kent who specializes in cartoons. One might show countries as animals rushing to feast on the same prey, for instance, as a metaphor for feuding over resources. “This attitude continued into the First World War, where nations aimed to highlight the differences between themselves and their enemies,” Gregory says.

While Sleigh’s map isn’t propaganda, some have read its storybook quality as a reaction to the tumultuous political climate that had plunged so many nations into the war. Chen says that the map is escapist, and it’s likely that resonated with viewers—and maybe was a balm for Sleigh himself. As Britain experienced national challenges, Sleigh was rattled by personal ones, including the dissolution of his marriage and a bicycling accident that nearly severed his thumb, threatening his livelihood as an artist. (He eventually mastered the art of gripping a paintbrush or pencil without that digit.) The public was eager to be enchanted—even by charming hoaxes, such as the Cottingley Fairies, photographic “proof” of fairies that was also produced in 1917. “Could the map constitute a yearning for a return to pre-1914 Edwardian innocence?” antiquarian cartography scholars Tim Bryars and Tom Harper ask in A History of the Twentieth Century in 100 Maps.

“Compared with the devastated, bomb-blasted landscape of northern France, this vision of a make-believe land may have seemed a seductive escape for a European society bearing the psychological and physical scars of mass conflict,” they write. The landscape rewards close, careful looking. “Each time you look at it, there’s some new thing that you didn’t notice was there last time,” Chen says. Despite the wild seas, foreboding castles, and forest of flames, the landscape overall is beautiful and welcoming. In 1917, that may have made it an appealing destination—however impossible.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook