What Would You Eat in a Cold War Fallout Shelter?

Nuclear war readiness meant stocking the pantry and recipes for canned ham salad.

In September 1961, the Charlotte News ran a column by food editor Marie Adams about preparing dishes that looked “as appetizing as possible—without benefit of cooking or heating.” But Adams wasn’t writing for people on a camping trip or weathering a long power outage at home. These recipes were intended for the “fallout shelter housewife.”

In her column, Adams provided a full heatless menu made with canned or jarred ingredients, like vichyssoise topped with dehydrated chives, and a spread for Saltines made with deviled ham, dried parsley, and canned mushrooms. She also suggests that her fellow homemakers prepare by testing out shelter-friendly menus in their home kitchens. After all, Adams says, “a few tricks up the sleeve are not amiss, even though we hope the chances are we shall never have to use them.”

A few days later, the paper published a scathing response from an anonymous reader who called Adams “more interested in the preservation of the symbols of affluence than in survival.” They disagreed with Adams’s assertion that she was taking the matter seriously. Instead of trying to make meals that look and taste pleasant with limited means, the reader suggests that Adams stock up on water and long-lasting, nutrient-dense foods like canned salmon, peanut butter, and even dog food. It wouldn’t be pretty, they added sarcastically, “but it is very nourishing and won’t spoil.”

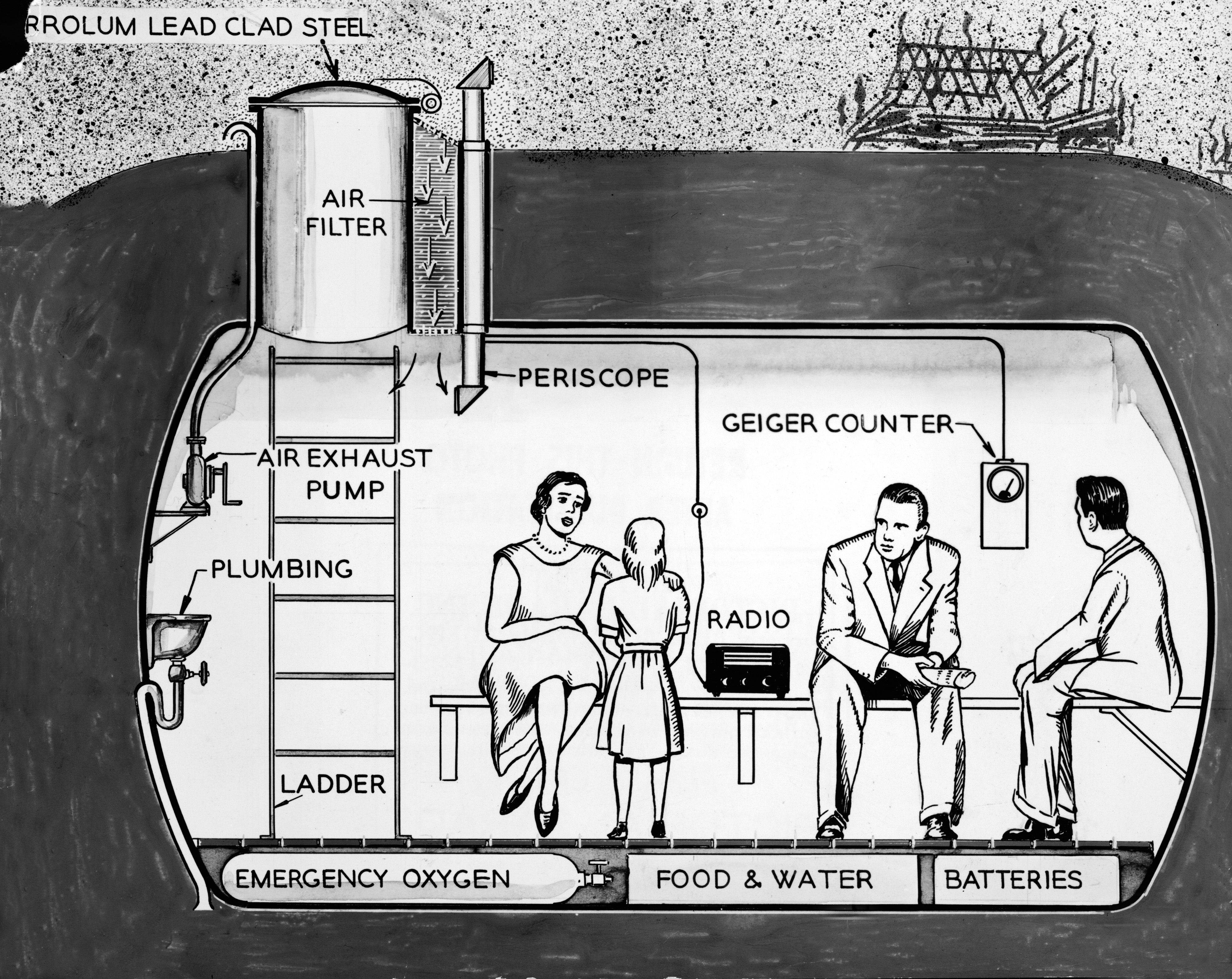

For many Americans in the late 1950s and early 1960s, the possibility of having to hide in underground shelters during a nuclear war with the Soviet Union felt real and terrifying. As Cold War tensions escalated, the US government realized that, if there was a nuclear attack, “they wouldn’t be able to provide for every person,” says Dr. Tom Bishop, Senior Lecturer in American History at the University of Lincoln, England.

However, the government still had to convince citizens of the necessity of stockpiling nuclear weapons for defense, in what Bishop calls the “big sales pitch” of the period. “But to get people to buy into that image,” Bishop adds, “you need to give them some form of survival narrative … you need to convince people that they have the means to survive, without actually really providing them anything.”

To avoid mass panic, authorities encouraged civilians to embrace what Bishop calls “the frontier spirit,” with the fallout shelter as “the log cabin of the nuclear age.” Government messaging claimed America was bountiful enough that, post-shelter, food could be harvested from the wild with ease, as much as a pound per day in some areas. “All of it’s pretty much nonsense,” says Bishop. “But it becomes a really powerful tool in trying to maintain … morale on the homefront during the Cold War.”

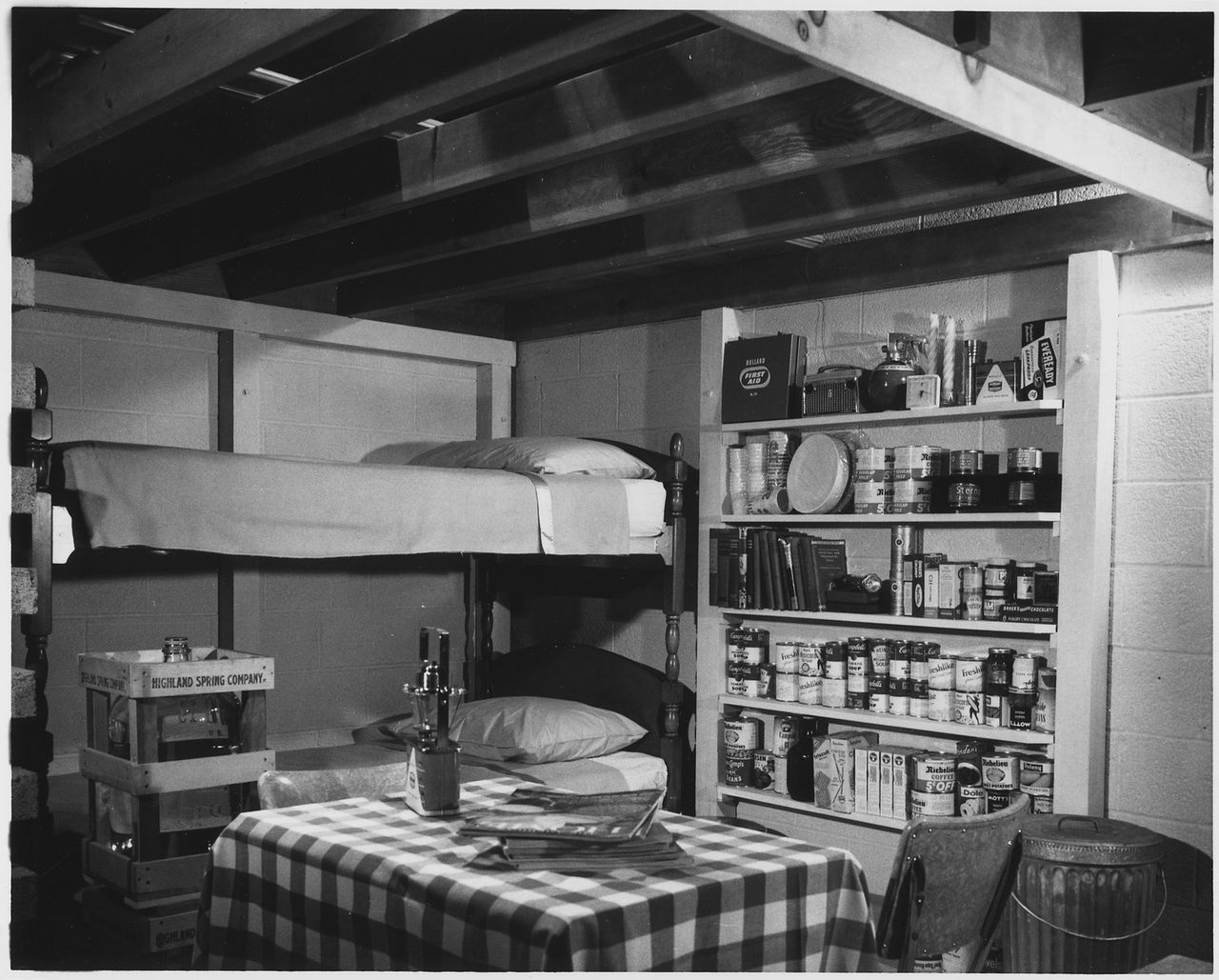

In 1961, President Kennedy sparked shelter mania when he stated in a Life magazine cover story that 97 percent of Americans could survive a nuclear attack if they retreated to a well-stocked fallout shelter. At the time, scientists believed that people would only have to wait out the effects of nuclear fallout for two weeks, after which they could safely return aboveground and rebuild society from the rubble.

Books like Family Food Stockpile for Survival, issued by the US Department of Agriculture in 1961, provided guidance on which foods keep longest and how to purify water for drinking. However, the book makes it clear that the “responsibility” of preparation “is placed directly on the individual citizen and family.” A government ad campaign called “Grandma’s Pantry” encouraged home food stockpiling with taglines like “Unexpected company? Grandma always had plenty for everyone.”

This framing hints at the expectation placed on women to prepare nourishing, satisfying meals, even during an apocalypse. Wives and mothers were often the intended audience of family preparedness guides, and women’s magazines issued shelter menus much like Marie Adams did in her column. Bishop describes the Cold War fallout shelter as “a microcosm of gender roles” in American society of the time, with government propaganda pushing a very specific “I Love Lucy, 1950s suburban image of what the family is supposed to be like.”

While men were cast in the role of protector, guiding the family to safety belowground, women, Bishop says, were expected to be “able to whip up these meals for families in two seconds and always have their home prepared.”

Ultimately, the government portrayed consumerism as the key to survival. Americans were led to believe that they had the means to protect their families, just as long as they bought enough of the right products. This emphasis on shopping as part of preparedness, Bishop notes, was “tapping into the people who have disposable income, to be able to afford it. So it’s survival for a certain section of the population. But it’s not survival for everyone else.”

Sears stacked Kellogg’s cornflakes, Campbell’s soup cans, and Tang drink mix together as part of “Grandma’s Pantry” displays. Other companies packaged two weeks’ worth of essentials into shelter kits under brand names like “Surviv-All,” which included several cans of “Multi-Purpose Food,” an emergency ration licensed by General Mills. Three two-ounce servings of MPF was supposed to provide the minimum daily caloric intake for an average adult. Consisting of soy-based granules enriched with vitamins, MPF had little flavor but was notably versatile, as it could be consumed wet or dry, hot or cold, by itself or mixed into other foods. General Mills suggested sprinkling it into tomato soup or onto a peanut butter sandwich.

While civilians were encouraged to take preparation into their own hands and private companies marketed emergency products, the federal government prepared to offset a nuclear disruption to the food supply chain. In 1958, government scientists identified bulgur, a traditional Middle Eastern grain product made from parboiled and dried wheat, as a promising emergency food for its nutritional value and long shelf life. Major snack companies like Keebler and Nabisco were contracted to produce thousands of tasteless but nourishing bulgur “survival crackers.”

Government officials recommended a daily ration of six crackers, combined with “carbohydrate supplements” in the form of hard candy, but this was considered only an absolute minimum. According to Bishop, the government never tested whether these crackers could sustain human life entirely on their own, and recommended them only in combination with other foods, perhaps because they were just so unpalatable.

States also created food contingency plans, from the practical to the wildly imaginative. This was especially true in the Midwest, where both human populations and chances of a direct nuclear attack were lower, providing more freedom to experiment. In Kansas, officials planned to confiscate vitamin pills and coffee from private homes to redistribute among survivors, and calculated available caloric reserves based on the state population of animals, including cats and dogs. In Nebraska, the state Department of Agriculture developed their own survival biscuits, which they branded as “Nebraskits.”

Nebraska also designed fallout shelters for livestock, constructing a 6,000-square foot bunker near Omaha that could hold up to 200 cattle. In 1963, a herd of 35 cows and one bull spent two weeks testing this shelter, along with two human caretakers. “We don’t want to look at another cow for a couple of weeks,” one caretaker said after returning aboveground. The cows lost some weight during the experiment, but were otherwise unaffected.

When the caretakers of the shelter cattle, who complained of the monotonous shelter diet, returned to the surface, they were greeted with sweet rolls and a pitcher of cold milk. Part of the reason Nebraskans were anxious to protect their cows was because of milk, considered both essential to a healthy diet and especially susceptible to fallout contamination.

Cattle were also significant because they represented, in Bishop’s words, “the myths of the West,” and the romantic idea “that if the cattle survive, that America survives in some form.” He connects the shelter cattle with a more-famous experiment conducted in 1959, when newlyweds honeymooned in a fallout shelter. Both the young married couple and the herd of cattle symbolized hope for the future. If they could survive two weeks underground, so could the rest of American society.

Bishop describes the nuclear hysteria of the Cold War as a time when, in spite of growing cynicism, “people still [have] this kind of faith in the government message … that President Kennedy wouldn’t lie to you. That if you build a bomb shelter, you’re going to be fine. The cattle are all going to be fine as well.” But as tensions with the USSR waned and the futility of anti-fallout measures became more apparent, both the US government and public largely dropped the idea of shelters as essential to American survival. By the 1970s, fallout shelters were already being looked back on as a fad, and the US government was attempting to offload 150,000 tons of uneaten survival crackers as aid relief, sending boxes of them to Guatemala after an earthquake in 1976. Unfortunately, the by-then spoiled crackers caused mass food poisoning. Many were trashed in landfills, while other caches are still being discovered today, and even tasted by some daring individuals.

Knowing what we know now, it’s easy to laugh at the seeming frivolity of Marie Adams trying to make dinner in a fallout shelter feel like home, or to accuse her, as the critical reader did, of vainly trying to maintain her “affluence.” Adams and her critic represent two possible responses to the fear of nuclear annihilation that gripped the American people during the Cold War. On one side was a grim pragmatism that prioritized survival over comfort. But on the other side was a sense of optimism: that even in the midst of a world-changing crisis, there would be ham salad.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook